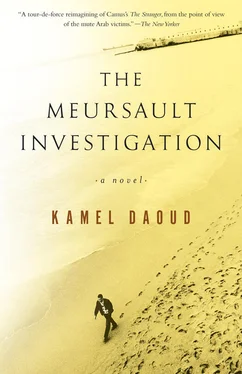

Kamel Daoud - The Meursault Investigation

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kamel Daoud - The Meursault Investigation» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Other Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Meursault Investigation

- Автор:

- Издательство:Other Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Meursault Investigation: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Meursault Investigation»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

In a bar in Oran, night after night, he ruminates on his solitude, on his broken heart, on his anger with men desperate for a god, and on his disarray when faced with a country that has so disappointed him. A stranger among his own people, he wants to be granted, finally, the right to die.

The Stranger

The Meursault Investigation

The Meursault Investigation — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Meursault Investigation», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Five days later, answering the summons I’d received from the country’s new leaders, I betook myself to the Hadjout town hall. There I was arrested and thrown into a room that already contained several people — a few Arabs (who doubtless hadn’t fought in the revolution or whom the revolution hadn’t killed), but mostly Frenchmen; I didn’t know any of them, not even by sight. Somebody asked me in French what I’d done. I answered that I was accused of having killed a Frenchman, and they were all silent. Night fell. Bugs tormented me in my sleep the whole night, but I was somewhat used to that. A sunbeam came through the skylight and woke me up. I heard noises in the corridors, footsteps, shouted orders. Nobody gave us any coffee. I waited. The French stared hard at the few Arabs, who scrutinized them in turn. Two djounoud eventually came in. When they thrust their chins in my direction, the guard grabbed me by the neck and pulled me outside. I was hustled into a jeep, and I figured I was being transferred to the police station, where they could put me in a cell by myself. The Algerian flag on the jeep flapped in the wind. Along the way, I saw my mother walking on the shoulder of the road, enveloped in her haik. She stopped to let the convoy pass. I smiled at her vaguely, but she remained stone-faced. I’m sure she followed us with her eyes before she started walking again. I was thrown into a cell, where I had a bucket for a toilet and a tin washbasin. The prison was situated in the center of town, and through a small window I could see some cypresses with whitewashed trunks. A guard came in and told me I had a visitor. I thought it must be my mother, and I was right.

I followed the taciturn guard the whole length of an endless corridor that led to a small room. Two djounoud were there, completely indifferent to us. They seemed weary, worn, and tense, with slightly crazy eyes, as if seeking the invisible enemy they’d spent years with the resistance on the lookout for. I turned to my mother; her face was closed but serene. She was sitting, straight-backed and dignified, on a wooden bench. The room we were in had two doors: the one I’d come through and another that opened into a second corridor. There I could see two little old French ladies. The first one was dressed all in black, and her lips were tightly closed. The second was a big woman with bushy hair who looked very nervous. I could also see into another room, most likely an office, with open folders, sheets of paper on the floor, and a broken windowpane. All was silent — a little too silent, in fact; it made it hard to find words. I didn’t know what to say. I speak very little to my mother, it’s been like that forever, and we weren’t used to having so many people around, hanging on our lips. Only one person had ever intruded on us, couple that we were, and I’d killed him. Here I had no weapon. Mama leaned toward me abruptly and I flinched hard, as if I might be struck in the face or devoured in one gulp. She spoke very fast: “I told him you were my only son and that was why you couldn’t join the resistance.” After a silent pause, she added: “I told them Musa died.” She was still talking about his death as if it had happened yesterday, or as if the date was a mere detail. She explained that she’d shown the colonel the two scraps of newspaper with the article about an Arab killed on a beach. The colonel had hesitated to believe her. No names were given, and there was nothing to prove she was really the mother of a martyr; and besides, could he even have been a martyr, since the crime dated from 1942? I told her, “It’s difficult to prove.” The fat Frenchwoman seemed to be following our discussion with tremendous concentration. I believe everyone was listening to us. Granted, there was nothing else to do. You could hear the birds outside, the sounds of engines, of trees reaching out to embrace in the wind, but none of that was very interesting. I had no idea what I could add. “I didn’t bawl like the other women. I think he believed me because of that,” she said in one urgent breath, as if murmuring a secret. However, I had already understood what she was really trying to tell me, and besides, the conversation was over.

I had the impression that everybody was waiting for an honorable exit, a sign, a snap of the fingers to wake them up, some way of closing the interview without looking ridiculous. I felt an immense weight on my shoulders. The meeting between a mother and an incarcerated son must end either in a tender embrace or in tears. And maybe one of us should have said something … But nothing was said, and the time seemed to drag on interminably. Then we heard the squealing of tires outside. My mother sprang nimbly to her feet. Out in the corridor, the old woman with the tight lips took the beginnings of a step. One of the soldiers came up to me and put his hand on my shoulder, the other coughed discreetly. The two Frenchwomen were staring at the end of the corridor, which I couldn’t see, I could just hear footsteps echoing down the hall. As they drew closer, I saw the two old women turn pale and shrink back with distorted faces, all the while shooting each other panicked looks. “It’s him, he speaks French,” the bigger of the two women said, pointing at me. Mama whispered, “The colonel believed me. When you get out, I’ll find you a wife.” Now there was a promise I wasn’t expecting. But I understood what she meant to say by it. Then I was brought back to my cell. Once inside, I sat down and looked out at the cypresses. All sorts of ideas were colliding in my head, but I felt calm, and I remembered Bab-el-Oued and our wanderings there, Mama’s and mine, our arrival here in this town, the light, the sky, the swans’ nests. In Hadjout I learned to hunt birds, but that ceased to amuse me as the years passed. Why didn’t I ever take up arms and join the resistance? Yes, that’s what you were obligated to do in those days, when you were young and you couldn’t go swimming. I was twenty-seven, and nobody in the village was able to understand why I hung around instead of going underground and joining “the brothers.” People in Hadjout had been making fun of me for a long time, ever since our arrival there. They thought I was sick or lacking male private parts or a prisoner of the woman who called herself my mother. When I was fifteen, I had to kill a dog with my own hands, using a blade fashioned from the lid of a sardine can, to make the boys of my age stop laughing at me and calling me a coward and a wimp. One day a man who was watching me play kickball in the street with some other kids suddenly called out, “Your legs don’t match.” At my mother’s insistence, I went to school, and very quickly I made enough progress to read her the fragments of newspapers she collected, with articles that told the story of how Musa had been killed but never gave his name, his neighborhood, his age, or even his initials. The truth is, we started the war — in a way — before the people did. Of course, I didn’t kill a Frenchman until July 1962, but our family had known death, martyrdom, exile, flight, hunger, grief, and pleas for justice at a time when the country’s war leaders were still playing marbles and lugging baskets in the markets in Algiers.

So at the age of twenty-seven, I was a sort of anomaly. And sooner or later, I’d have to answer for it before an officer in the Army of National Liberation. Meanwhile time passed in the sky I could see through the window, and it passed in the color of the trees, which became dark and murmurous. The guard brought me a meal and I thanked him, and then I thought it would be a great pleasure to sleep some more. I felt thoroughly free in my cell, without Mama or Musa. Before leaving me alone, the guard turned around and fired a question at me: “Why didn’t you help the brothers?” He said it without nastiness, with kindness even, and with a certain curiosity. I didn’t collaborate with the colonists and everyone in the village knew it, but I wasn’t a mujahid either, and it bothered a great many people that I was sitting there in the middle, in that intermediary state, as if I was taking a nap under a rock on the beach or kissing a beautiful young woman’s breasts while my mother was getting robbed or raped. “They’re going to ask you that,” the guard threw out before closing the cell door. I knew what he was talking about. Afterward I slept, but before that, I listened. It was all I had to do, I didn’t smoke, and I hadn’t minded when they took my shoelaces and my belt and everything I had in my pockets. I didn’t want to kill time. I don’t like that expression. I like to look at time, follow it with my eyes, take what I can. For once, there was no corpse on my back! I decided to enjoy my idleness. Did I think about how badly the next day could turn out? A little, no doubt, but I didn’t dwell on it. Death was something I was strangely used to. I could move from the living to the deceased, from the hereafter to the sun, just by changing the given names: Harun (my name), Musa, Meursault, or Joseph. According to preference, almost. In the first days of Independence, death was as gratuitous, absurd, and unexpected as it had been on a sunny beach in 1942. I could be accused of anything, my chances of being shot as an example or set free with a kick in the butt were just about equal, and I knew it. Then evening came along with a handful of stars, and the darkness dug a hole in my cell, blurred the outlines of the walls, and brought a sweet smell of grass. It was still summer, and by peering into the blackness I was eventually able to glimpse a bit of the moon, which was slowly sliding my way. I slept again, for a very long time, while unseen trees tried to walk, flailing about with their big branches in the effort to free their black, fragrant trunks. My ear was glued to the ground of their struggle.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Meursault Investigation»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Meursault Investigation» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Meursault Investigation» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.