He kneels, an impromptu confessional, might buy him a reprieve.

Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. I left my brother Bobby at the beach.

“Shut up, Franky. You’re drunk,” Peter says, softly, with a smile. He’s older, wearing a sweater, ready to carve the roast.

“I know what you’re all thinking.” His voice, older, but the boy waits. “I know what you’re all thinking.”

The words preordained, rehearsed, already spoken. The déjà vu of all dreams.

“I mean it, Franky, leave. Now.”

A car on the street turning into the driveway. Waiting.

“Franky, stop it, please,” Tina says from the other room. “Please.”

The sound of a car door slamming. One door.

“It’s what you’ve all been thinking for years, since the day it happened.”

The doorknob turning. He’s scared now, more frightened than he’s ever been. The door opens. His mother. Alone.

“Where’s Bobby?”

“I couldn’t find him.”

“It should have been me, that’s what you’re all thinking. Say it.”

Don’t say it.

“Out, Franky. Get out of my house.”

“You wish it was me. Not Bobby. Say it.”

Don’t say it. Please don’t say it.

“Where’s Bobby?”

“I couldn’t find him.”

“ Say it, Tina, you can say it. You should say it.”

His mother walks in, kneels down, holds his cheeks with her hands.

“Say it, Mom. I know you want to. You wish it was me. You wish it had been me, instead of Bobby. Say it.”

Don’t say it.

His teeth crack in his mouth, drift into the air. Her voice is steady, an arrow in flight.

“You’re right.”

* * *

Franky opens his eyes. He’s on the edge of a small bed, pushed there by Chrissy Nolan’s awkward bulk and selfish sleeping habits. His bloody cheek is stuck to the bedsheet; he pulls it away delicately but it still stings. He slides out of bed, in search of the bathroom. He stumbles in pain. He looks down, spots an ugly raspberry on his thigh; he must have landed on that as well.

He inspects his face in the mirror. His left cheek is shredded, oozing yellow and puckered red. With his pinky, he pries a small black pebble out of it. His left eye is swollen nearly shut. How the hell is he gonna explain this? Fuck it, worry about it later.

He takes a piss. His prick is tender. She was enthusiastic, he remembers that much. Maybe he should stay, try to sleep a little more, go another round with Chrissy in a few hours.

Something she said last night is gnawing at him, about giving Bobby a blow job. No fucking way Bobby would have fooled around with that skank. No fucking way. He was only ever with Tina. If anyone would know whether Bobby got a BJ in the back room of the Leaf, it would be Franky. He has half a mind to stick around to make sure the bitch isn’t spreading false rumors.

No, he should go. Get out while the getting’s good. He has little Bobby’s birthday party later.

The present! Where the fuck is the present?

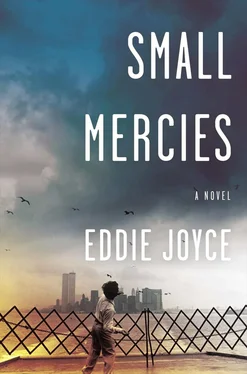

He sneaks back into the bedroom. Nothing. He goes to the kitchen, naked and cold. On the counter next to the fridge sits the plastic bag holding Bobby’s present. Small mercies.

He moves quietly back to the bedroom. Chrissy hasn’t moved an inch, is still snoring like a bear. He grabs his clothes from the floor. He dresses hastily, clumsily, in the kitchen; grabs the bag, shoves his feet into his sneakers, and leaves.

He walks out into gray silence. He looks around, unsure where he is. All he knows for sure is that he’s still on the Island; they didn’t cross water last night. At the end of the street, a stoplight switches needlessly from green to yellow to red. He follows the sidewalk up to the intersection, rain finding its way to him through the barren branches of trees. When he reaches the corner, he can sense the sun slowly rising behind the clouds.

Another day, infected by all that preceded it.

Chapter 9 ALL TOMORROW’S PARTIES

A drizzly Sunday, a day to stay in bed. Michael obliges, but Gail cannot. She has one last thing to do. She drives to the beach.

She’s been avoiding this all week, sparing herself the anguish. Losing herself in daydreams. She can’t put it off any longer. This afternoon, Tina is bringing a man to her house and she cannot let this man — this stranger —cross her threshold without telling Bobby. He has to know.

She winds her way through Gateway park down to the little spit of land that juts out into the bay. She parks the car and steps out into a cool spray; the wind pushes rain in from the bay. A bit of fog obscures the water, but she can hear the gentle lapping of the tide. She looks across the inlet to the marina. Boats sway gently in their docks. A few gulls fly idly overhead. Two other cars in the lot, but not a soul in sight. Still places on this Island where you can achieve a bit of solitude, lose yourself.

She found him here once, red-eyed and furious. A scared little boy. His older brothers played a prank, left him behind. The typical boy nonsense — two older brothers picking on the runt of the litter — but with a hint of real cruelty. It was Franky’s idea, Peter the reluctant co-conspirator. She found him on the beach, crying in the darkness. So angry.

“Why?” he asked. “Why did they do it?”

One of those questions. He may as well have asked her about the cruelty of life. And then she realized that he had. She held him and he sobbed into her chest. Held him as some tiny, tender part of him turned to stone. Only a sliver, but still.

She cleaned him up, took him for a cone, drove him home in the front seat. She told him to slink down in the seat as they pulled into the driveway. A second prank, crueler on account of the prankster. But she had a lesson to impart. She told Franky she couldn’t find Bobby, even though he was safe and secure, giggling in the car in the driveway.

Wisdom is cruelty, thinly disguised. She often thinks she lost Franky that night. He didn’t stop sobbing for hours, not even when it was clear that Bobby was fine. After that little escapade, Peter kept Franky and his bad ideas at a distance. Drifted away from his brother, as he would later drift away from the whole family. Nothing dramatic, nothing formal. A simple recognition: Franky was an anchor, not someone he wanted to be tied to. Best to leave him alone.

Bobby, bless him, went the other way. Forgave Franky, almost immediately, and they soon became thick as thieves. Stayed that way, more or less, until Bobby was killed.

As for Franky himself, it was like she’d alerted him to his capacity for cruelty, alerted him to his true nature. That’s how she thinks of it, never mind that he woke up the next morning like nothing had happened. Went straight back to the same song and dance.

To be a mother is to blame yourself. Take on their failings so they don’t have to. Her little lesson caused all of Franky’s problems. A fine bit of nonsense. Bullshit of the finest grain. She knows that.

But the look on his face when she walked in alone…

Damn it.

She’s getting distracted, excoriating herself over Franky. Wasn’t Peter there as well? He shook it off: took his punishment, apologized, and moved on. Doesn’t matter. This isn’t about Franky. Or Peter.

She needs to tell Bobby. He deserves this time with her, alone, without his brothers.

She talks to him all the time. In the house, in the car. Whenever she needs to. Nothing profound. Just a chat, like he was sitting beside her. Sometimes she thinks the words; sometimes she says them out loud, softly. Michael has caught her a few times, in mid-sentence; looked around the room to make sure he wasn’t crazy, that there wasn’t actually someone there he couldn’t see. He never says anything, though. He’s a good man that way, Michael. Respects a person’s right to be crazy in their own fashion.

Читать дальше