And there was only one person whose judgment Michael trusted more.

* * *

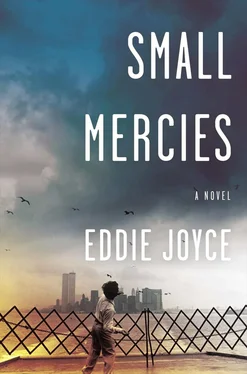

He finds Gus on the back porch, smoking a cigar he isn’t supposed to be smoking. Gus is staring across the bay at the base of Manhattan, where the tips of the Twin Towers are shrouded in fog. A few weeks ago, some Arabs detonated a bomb in the North Tower, killing six people. But it could have been a lot worse.

“I guess they thought they were gonna bring them down.”

Gus jumps, startled by Michael’s voice.

“You scared me. Thought you were Nancy.”

He looks back across at the towers.

“Guess so. I don’t know, Mikey, this world, I don’t understand it anymore.”

“That why you’re so intent on leaving it?”

Michael points to the cigar. Gus is much thinner than he used to be, thinner even than the last time Michael saw him.

“I’m eighty years old, you dumb ginny bastard. Let me enjoy myself. Make yourself useful, anyway, and fetch me a blanket.”

Michael goes inside, grabs an afghan, lays it on his mentor’s lap. He sits down next to him, takes in the view, always breathtaking. Two ferries pass in the harbor.

“I was on my way to drop off some entries at Cody’s, figured I’d drop by and see if you croaked yet.”

Gus laughs. After a few seconds, his laughter stumbles into a coughing fit.

“Don’t make me laugh, you bastard.” He stubs the cigar out in an ashtray on the table between them. “How’s it looking?”

“They’re saying two hundred grand, maybe more.”

He reaches under his blanket, pulls out an envelope, hands it to Michael.

“Just one sheet. With my luck, I’ll finally win this year but be too dead to collect.”

Michael laughs. Gus reaches over and grabs his arm.

“Mikey, if anything ever happened and I did win, you’d make sure that Nancy, you know—”

“ Marone, Gussy. Of course. You’re not gonna die,” he says, patting his mentor’s hand. “And you’re definitely not gonna win.”

“You little prick.”

“Learned from the best.”

Gus leans over.

“Listen, Mikey, there’s a bottle of scotch in the kitchen, in the pantry, behind the cereal boxes. Go get it, bring back two glasses. I hear we have something to celebrate.”

Michael retrieves the bottle, trying to ignore the decrepit state of the house. Dirty dishes are piled on the counters. Cabinet doors dangle off their hinges. There’s a hole near the sink and not a small one. The house was always a wreck, but now it’s dangerous. Feels like it might fall down at any moment. When he gets outside, he pours them each a finger of whiskey. Gus shakes his glass in irritation.

“Don’t be such a miser.”

Michael pours him another finger. They clink glasses.

“Congrats, Mikey.”

“Twenty-five years.”

“You did the most important thing, kid. Came home at the end of every shift. That’s the trick.”

“Went fast.”

“Tell me about it.”

They take sips, look out over the city. The whiskey tingles Michael’s tongue, sends warm emissaries to his extremities.

“City’s changed, mostly for the better,” Michael says. He looks over, sees Gus pulling the blanket up over his chest. He can still remember the night he met the legendary Gus Feeney. Now, the legend needs a blanket to stay warm, has to sneak cigars when his old lady is out.

“Everywhere but here. That goddamn bridge.”

The population on the Island has risen steadily since the bridge was finished. There’s construction everywhere; it’s like some of the builders have personal vendettas against trees. The Island is starting to lose its small-town feel.

“You were right, Gussy.”

Gus takes a long pull on his glass, closes his eyes.

“So, Mikey, what are you gonna do now?”

“Play some golf, relax, enjoy myself.”

“Seriously, what are you gonna do?”

“I am serious.”

“You’re a young man, Mikey. You need to find something else to do. Otherwise, this”— Gus raises his glass—“is what you’ll do.”

“I’ll figure it out.”

“You want me to make some calls, set you up someplace in the city, a cushy consulting gig, advising companies how to respond to fires, something like that?”

“I’m done commuting to the city.”

Gus takes a long pull, motions for Michael to refill his glass.

“Your father still have that shop?”

Michael can see his father holding an apron, triumphant at last. A quarter century, an entire career; these mean nothing. The shop is still waiting for him.

“I’m sure I could get a few shifts at the Leaf if I wanted.”

“You’re gonna bartend?”

“Maybe, I don’t know, Gus. I’ll figure it out.”

“The shop, would he give it to you? Or sell it on the cheap?”

“Of course. He’s been waiting thirty years to give me that fucking shop. I’m not gonna be a butcher, Gus. That ship has sailed.”

Gus reaches over and pokes him in the shoulder. Hard. Michael turns. There’s something close to anger in Gus’s eyes.

“Hey, jackass, don’t look a gift horse in the mouth.”

* * *

Tiny waits in the car while Michael goes to fetch Franky. He lives on the second floor of an old Victorian in Westerleigh, above an elderly widower whose lack of hearing and genial nature are the only things that have prevented his eviction. Michael goes up the back staircase, knocks on the door. Franky answers, holding a beer in one hand and a few entry sheets in the other.

“Daddy-o,” he says, giving Michael a hug. He smells sour, overripe. Not from the beer this morning, but from too much generally. He’s half pickled; he doesn’t look well.

“A little early, no?” Michael asks.

“It’s almost three. And, what, you didn’t have a few pops at the Leaf already?”

“Fair enough. You ready?”

“Give me two minutes. C’mon in. The games are in full swing. You want one?”

“No, I’m all set.”

They walk into the living room, which is less of a wreck than the last time Michael was here, nine months ago, looking for drugs. Franky has his sheets lined up in rows on a coffee table; envelopes of money lay scattered about. The television is on, the volume is low. Butler, an 8 seed, is playing Old Dominion, a 9 seed. Ten minutes left in the second half. A nail-biter. Michael reaches into his jacket, pulls out his sheet.

“So, Franky, I’m only putting in one entry sheet this year.”

“Really?”

“I’m doing it the way we used to do it. I pick a team, Peter picks a team, you pick a team. I asked Tina to pick for Bobby. I’ll call your Mom later and ask her to pick the winner.”

“Nice. Old school.”

“So it’s down to you.”

“What region?”

“Southeast.”

“Okay, let’s see. Who did everyone else pick?”

“Not gonna tell you.”

“I like it. Nice.”

He picks up a sheet, starts perusing the teams, talking to himself out loud.

“You and Petey definitely went chalk. Always have. I have no clue what Tina did, but Maria Terrio went to Notre Dame, so she probably picked them, in which case we’re all screwed anyway. But you gotta have faith, right? Okay. Pitt? No. Florida? Maybe. BYU? No fucking chance. Wisco? Maybe.”

Michael smiles at Franky’s logic. This is what he wanted. This is what he remembers: the boys treating the pool like it was a sacred thing, an institution. Franky looks up at the television. The game is tied, looks like it’s gonna go down to the wire.

“I’ll tell you what, Daddy-o. These two teams are really, really good. Whoever wins this game could give Pitt a real fight and then, who knows? Give me Butler. If Old Dominion wins, we can change when we’re in line.”

Читать дальше