When I can take no more of the Abbé Carlos Herrera (I could take none of Captain Edward Waverly) I cast about for something else, anything else, to read. In the drawer of a crazed and knobby end table I find an inch-thick typescript of yellow copy paper bound into a school report binder, the title inked in block capitals on white adhesive tape: WHAT I DID UNTIL THE DOCTOR CAME. I read the first sentence— In a sense, I am Jacob Horner —and then the others.

The narrative is crude, fragmentary, even dull — yet appealingly terse, laconic, spent. I have no idea whether it is “true” or meant as fiction, but I see at once how I might transform it to my purposes. Now I am impatient for the precious holiday to end!

I leave the typescript where I found it; all I need is the memory of its voice. Once back in the college’s faculty housing project, I write the novel very quickly — changing the locale and the names of all but the central character, making the Doctor black and anonymous, clarifying and intensifying the moral and dramatic voltages, adding the metaphor of paralysis, the small-time academic setting, the semiphilosophical dialogues and ratiocinations, the ménage à trois, the pregnancy, abortion, and other things. Now and then, after its publication in 1958, it occurs to me to wonder whether the unknown author of What I Did Until the Doctor Came ever happened upon my orchestration of his theme. But I am too preoccupied with its successor to wonder very much.

Well. I don’t recount, I only invent: the above is a fiction about a fiction. But it is a fact that after The End of the Road was published I received letters from people who either intimated that they knew where my Remobilization Farm was or hoped I would tell them; and several of the therapies I’d concocted for my Doctor — Scriptotherapy, Mythotherapy, Agapotherapy — were subsequently named in the advertisements of a private mental hospital on Long Island. Art and life are symbiotic.

Now there is money for baby-sitters, but I don’t need them. I’ve changed cities and literary principles, made up other stories, learned with mixed feelings more about the world and Yours Truly. Currently I find myself involved in a longish epistolary novel, of which I know so far only that it will be regressively traditional in manner; that it will not be obscure, difficult, or dense in the Modernist fashion; that its action will occur mainly in the historical present, in tidewater Maryland and on the Niagara Frontier; that it will hazard the resurrection of characters from my previous fiction, or their proxies, as well as extending the fictions themselves, but will not presume, on the reader’s part, familiarity with those fictions, which I cannot myself remember in detail. In addition, it may have in passing something to do with alphabetical letters.

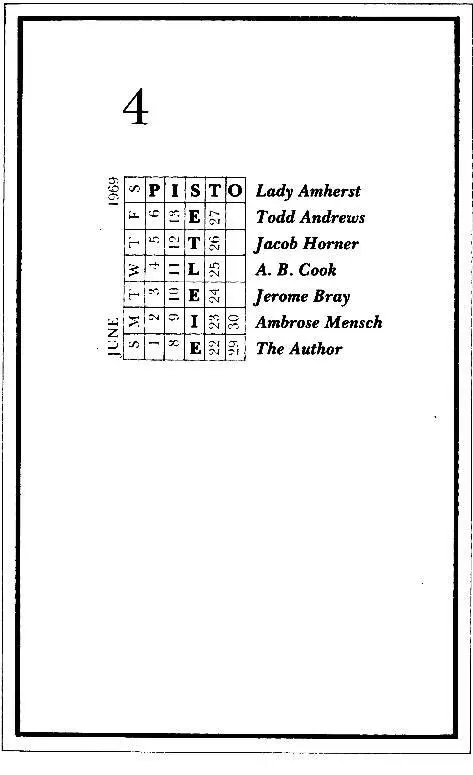

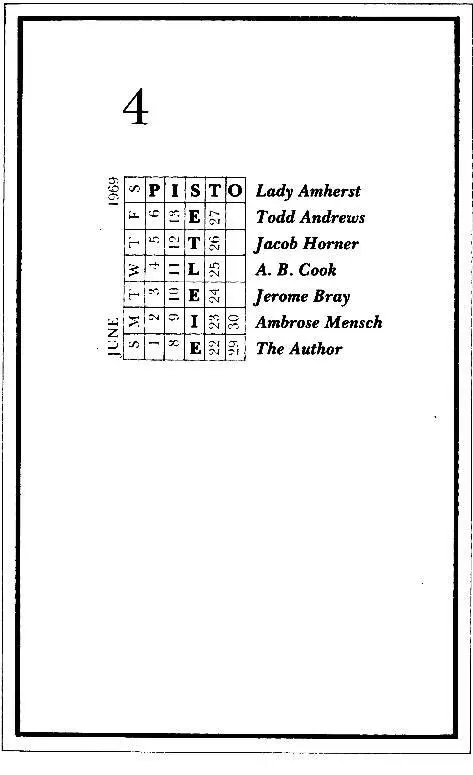

Of the epistles which are to comprise it, a few, like this one, will be from “the Author.” Some others will be addressed to him. One of the latter, dated May 3, 1969, I received last week from a certain Germaine Pitt, Lady Amherst, acting provost of the Faculty of Letters at “Marshyhope State University College” in Maryland. In the course of it Mrs. Pitt mentions having visited in 1967 a sort of sanatorium in Fort Erie, Ontario, “very much like the one described in The End of the Road,” complete with an unnamed elderly black physician. The lady did not mention a “Jacob Horner” among the patients or staff (she was there only briefly); but the fact that her letters speak in another context of a “Joseph Morgan” (former president of the college, whereabouts presently unknown) and a “John Schott” (his successor) prompts this inquiry.

That you have received and are reading it proves that its proximate address and addressee exist. Were they ever located in the Allegheny Valley, beneath the present Kinzua Reservoir? Are you the author of What I Did Until the Doctor Came? My having imagined that serendipitous discovery does not preclude such a manuscript’s possible existence, or such an author’s. On the contrary, my experience has been that if anything it increases the likelihood of their existing — a good argument for steering clear of traditional realism.

Do you know what happened to the unfortunate “Joe Morgan”? Are you still subject to spells of “weatherlessness” and the paralytic effect of the Cosmic View? Do you still regard yourself as being only “in a sense” Jacob Horner? That whole business of ontological instability — not to mention accidental pregnancy and illegal abortion — seems now so quaint and brave an aspect of the early 1950’s (and our early twenties) that it would be amusing, perhaps suggestive, to hear how it looks to you from this perspective. If you did indeed write such a memoir or manuscript fiction as What I Did etc., and my End of the Road caused you any sort of unpleasantness, my belated apologies: if literature must sometimes be written in blood, it should be none but the author’s.

I’d be pleased to hear from you; could easily drive over to Fort Erie from Buffalo for a chat, if you’d prefer.

Cordially,

P: Lady Amherst to the Author.The Fourth Stage of her affair. She calls on A. B. Cook VI in Chautaugua. Ambrose’s Perseus project, and a proposition.

Office of the Provost

Faculty of Letters

Marshyhope State University

Redmans Neck, Maryland 21612

7 June 1969

John, John,

Provost indeed! What am I doing here, in this getup, in this office, in this country? And what are the pack of you doing to me?

Driving me bonkers, is what — you and Ambrose and André, André—straight out of my carton, as the children say. And I, well, it seems I’m doing what my “lover” claims to’ve devoted a period of his queer career to: answering rhetorical questions; saying clearly and completely what doubtless goes without saying.

E.g., that my apprehensions re the “4th Stage” of our affair prove in the event to have been more than justified. Every third evening, sir, regardless of my needs and wants — indeed, regardless of Ambrose’s needs and wants too, in the way of simple pleasure — I am courteously but firmly fucked, no other way to put it, in the manner set forth two letters past, to the sole and Catholic end of begetting a child. ’Appen I enjoy it (as, despite all and faute de mieux, I sometimes do), bully for me; ’appen I don’t, it up wi’ me knees and nightie anyroad, and to’t till I’m proper ploughed and seeded. In this business, and currently this only, the man is husbandly, John, as aforedescribed: husbanding his erections, husbanding my orgasms, his ejaculate. His eye like an old-time crofter’s is upon the calendar: come mid-lunation we are to increase our frequency to two infusions daily in hopes of nailing June’s wee ovum, May’s having given us the slip.

As I too must hope “we” do — yet how hope a hope so hopeless? Why, because, if this old provostial organ do not conceive, I truly fear the consequence! Silent sir (you who mock me not only by your absence from this “correspondence” but by your duly reported presence, even as I write these words, just across the Bay in College Park, to accept the honour you would not have from us. O vanity!): what I feared in mine of Saturday last is come to pass: our friend Ambrose has turned tyrant! Witness: I write this on office stationery because — for all it’s a muggy Maryland late-spring Saturday, the students long since flown for the summer, the campus abandoned till our anticlimactic commencement exercises a fortnight hence — I am in my office, winding up my desk work and putting correspondence on the machine for Shirley Stickles. And I am here not at all because the week’s work has spilled into the weekend. Au contraire: since our (early) final examinations put a term, hic et ubique, to the most violent term in U.S. academic history — one which I wot will mark a turn for ill and ever in the fortunes of many a college in this strange country — there’s been little to do, acting-provostwise. No: I am here now because I’m ashamed to show myself to Stickles, Schott, & Co., and so must do my windup work by weekend and weeknight, always excepting those reserved for conjugation.

Читать дальше