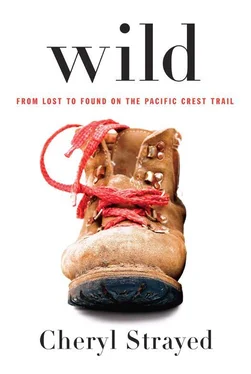

Cheryl Strayed - Wild

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cheryl Strayed - Wild» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Wild

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:978-0-307-95765-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wild: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Wild»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Wild — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Wild», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Being in their company felt like a holiday.

We walked to the campsite the store set aside for us, where the Three Young Bucks had already ditched their packs, and we cooked dinner and talked and told stories about things both on and off the trail. I liked them immensely. We clicked. They were sweet, cute, funny, kind guys and they made me forget how ruined I’d felt just an hour before. In their honor, I made the freeze-dried raspberry cobbler I’d been carrying for weeks, saving it for a special occasion. When it was done, we ate it with four spoons from my pot and then slept in a row under the stars.

In the morning, we collected our boxes and took them back to our camp to reorganize our packs before heading on. I opened my box and pushed my hands through the smooth ziplock bags of food, feeling for the envelope that would contain my twenty-dollar bill. It had become such a familiar thrill for me now, that envelope with the money inside, but this time I couldn’t find it. I dumped everything out and ran my fingers along the folds inside the box, searching for it, but it wasn’t there. I didn’t know why. It just wasn’t. I had six dollars and twelve cents.

“Shit,” I said.

“What?” asked one of the Young Bucks.

“Nothing,” I said. It was embarrassing to me that I was constantly broke, that no one was standing invisibly behind me with a credit card or a bank account.

I loaded my food into my old blue bag, sick with the knowledge that I’d have to hike 143 miles to my next box with only six dollars and twelve cents in my pocket. At least I didn’t need money where I was going, I reasoned, in order to calm myself. I was heading through the heart of Oregon — over Willamette Pass and McKenzie Pass and Santiam Pass, through the Three Sisters and Mount Washington and Mount Jefferson Wildernesses — and there’d be no place to spend my six dollars and twelve cents anyway, right?

I hiked out an hour later with the Three Young Bucks, crisscrossing with them all day; occasionally we stopped together for breaks. I was amazed by what they ate and how they ate it. They were like barbarians loose upon the land, shoving three Snickers bars apiece into their mouths on a single fifteen-minute break, though they were thin as sticks. When they took off their shirts, their ribs showed right through. I’d lost weight too, but not as much as the men — an unjust pattern I’d observed across the board in the other male and female hikers I’d met that summer as well — but I didn’t much care anymore whether I was fat or thin. I cared only about getting more food. I was a barbarian too, my hunger voracious and monumental. I’d reached the point where if a character in one of the novels I was reading happened to be eating, I had to skip over the scene because it simply hurt too much to read about what I wanted and couldn’t have.

I said goodbye to the Three Young Bucks that afternoon. They were going to push on a few miles past where I planned to camp because in addition to being three young incredible hiking machines, they were eager to reach Santiam Pass, where they’d be getting off the trail for a few days to visit friends and family. While they were living it up, showering and sleeping in actual beds and eating foods I didn’t even want to imagine, I’d get ahead of them again and they’d once more be following my tracks.

“Catch me if you can,” I said, hoping they would, sad to part ways with them so soon. I camped alone near a pond that evening still aglow from having met them, thinking about the stories they’d told me, as I massaged my feet after dinner. Another one of my blackened toenails was separating from my toe. I gave it a tug and it came all the way off. I tossed it into the grass.

Now the PCT and I were tied. The score was 5–5.

I sat in my tent with my feet propped up on my food bag, reading the book I’d gotten in my box — Maria Dermoût’s The Ten Thousand Things —until I couldn’t keep my eyes open anymore. I turned off my headlamp and lay in the dark. As I dozed off, I heard an owl in a tree directly overhead. Who-whoo, who-whoo , it hooted with a call that was at once so strong and so gentle that I woke up.

“Who-whoo,” I called back to it, and the owl was silent.

“Who-whoo,” I tried again.

“Who-whoo,” it replied.

I hiked into the Three Sisters Wilderness, named for the South, North, and Middle Sister mountains in its boundaries. Each of the Sister peaks was more than 10,000 feet high, the third-, fourth-, and fifth-highest peaks in Oregon. They were the crown jewels among a relatively close gathering of volcanic peaks I’d be passing in the coming week, but I couldn’t see them yet as I approached from the south on the PCT, singing songs and reciting scraps of poems in my head as I hiked through a tall forest of Douglas firs, white pines, and mountain hemlocks, past lakes and ponds.

A couple of days after I’d said goodbye to the Three Young Bucks, I took a detour a mile off the trail to the Elk Lake Resort, a place mentioned in my guidebook. It was a little lakeside store that catered to fishermen, much like the Shelter Cove Resort, only it had a café that served burgers. I hadn’t planned to make the detour, but when I reached the trail junction on the PCT, my endless hunger won out. I arrived just before eleven in the morning. I was the only person in the place aside from the man who worked there. I scanned the menu, did the math, and ordered a cheeseburger and fries and a small Coke; then I sat eating them in a rapture, backed by walls lined with fishing lures. My bill was six dollars and ten cents. For the first time in my entire life, I couldn’t leave a tip. To leave the two pennies I had left would’ve seemed an insult. I pulled out a little rectangle of stamps I had in the ziplock bag that held my driver’s license and placed it near my plate.

“I’m sorry — I don’t have anything extra, but I left you something else,” I said, too embarrassed to say what it was.

The man only shook his head and murmured something I couldn’t make out.

I walked down to the empty little beach along Elk Lake with the two pennies in my hand, wondering if I should toss them into the water and make a wish. I decided against it and put them in my shorts pocket, just in case I needed two cents between now and the Olallie Lake ranger station, which was still a sobering hundred miles away. Having nothing more than those two pennies was both horrible and just the slightest bit funny, the way being flat broke at times seemed to me. As I stood there gazing at Elk Lake, it occurred to me for the first time that growing up poor had come in handy. I probably wouldn’t have been fearless enough to go on such a trip with so little money if I hadn’t grown up without it. I’d always thought of my family’s economic standing in terms of what I didn’t get: camp and lessons and travel and college tuition and the inexplicable ease that comes when you’ve got access to a credit card that someone else is paying off. But now I could see the line between this and that — between a childhood in which I saw my mother and stepfather forging ahead over and over again with two pennies in their pocket and my own general sense that I could do it too. Before I left, I hadn’t calculated how much my journey would reasonably be expected to cost and saved up that amount plus enough to be my cushion against unexpected expenses. If I’d done that, I wouldn’t have been here, eighty-some days out on the PCT, broke, but okay — getting to do what I wanted to do even though a reasonable person would have said I couldn’t afford to do it.

I hiked on, ascending to a 6,500-foot viewpoint from which I could see the peaks to the north and east: Bachelor Butte and glaciated Broken Top and — highest of them all — South Sister, which rose to 10,358 feet. My guidebook told me that it was the youngest, tallest, and most symmetrical of the Three Sisters. It was composed of over two dozen different kinds of volcanic rock, but it all looked like one reddish-brown mountain to me, its upper slopes laced with snow. As I hiked into the day, the air shifted and warmed again and I felt as if I were back in California, with the heat and the way the vistas opened up for miles across the rocky and green land.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Wild»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Wild» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Wild» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.