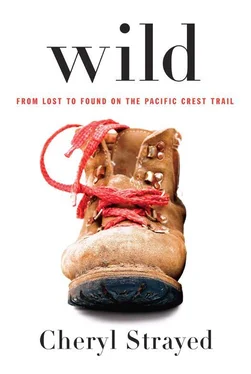

Cheryl Strayed - Wild

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cheryl Strayed - Wild» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Wild

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:978-0-307-95765-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wild: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Wild»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Wild — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Wild», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This was not so.

We were led into an examining room, where a nurse instructed my mother to remove her shirt and put on a cotton smock with strings that dangled at her sides. When my mother had done so, she climbed onto a padded table with white paper stretched over it. Each time she moved, the room was on fire with the paper ripping and crinkling beneath her. I could see her naked back, the small curve of flesh beneath her waist. She was not going to die. Her naked back seemed proof of that. I was staring at it when the real doctor came into the room and said my mother would be lucky if she lived a year. He explained that they would not attempt to cure her, that she was incurable. There was nothing that could have been done, he told us. Finding it so late was common, when it came to lung cancer.

“But she’s not a smoker,” I countered, as if I could talk him out of the diagnosis, as if cancer moved along reasonable, negotiable lines. “She only smoked when she was younger. She hasn’t had a cigarette for years.”

The doctor shook his head sadly and pressed on. He had a job to do. They could try to ease the pain in her back with radiation, he offered. Radiation might reduce the size of the tumors that were growing along the entire length of her spine.

I did not cry. I only breathed. Horribly. Intentionally. And then forgot to breathe. I’d fainted once — furious, age three, holding my breath because I didn’t want to get out of the bathtub, too young to remember it myself. What did you do? What did you do? I’d asked my mother all through my childhood, making her tell me the story again and again, amazed and delighted by my own impetuous will. She’d held out her hands and watched me turn blue, my mother had always told me. She’d waited me out until my head fell into her palms and I took a breath and came back to life.

Breathe .

“Can I ride my horse?” my mother asked the real doctor. She sat with her hands folded tightly together and her ankles hooked one to the other. Shackled to herself.

In reply, he took a pencil, stood it upright on the edge of the sink, and tapped it hard on the surface. “This is your spine after radiation,” he said. “One jolt and your bones could crumble like a dry cracker.”

We went to the women’s restroom. Each of us locked in separate stalls, weeping. We didn’t exchange a word. Not because we felt so alone in our grief, but because we were so together in it, as if we were one body instead of two. I could feel my mother’s weight leaning against the door, her hands slapping slowly against it, causing the entire frame of the bathroom stalls to shake. Later we came out to wash our hands and faces, watching each other in the bright mirror.

We were sent to the pharmacy to wait. I sat between my mother and Eddie in my green pantsuit, the green bow miraculously still in my hair. There was a big bald boy in an old man’s lap. There was a woman who had an arm that swung wildly from the elbow. She held it stiffly with the other hand, trying to calm it. She waited. We waited. There was a beautiful dark-haired woman who sat in a wheelchair. She wore a purple hat and a handful of diamond rings. We could not take our eyes off her. She spoke in Spanish to the people gathered around her, her family and perhaps her husband.

“Do you think she has cancer?” my mother whispered loudly to me.

Eddie sat on my other side, but I could not look at him. If I looked at him we would both crumble like dry crackers. I thought about my older sister, Karen, and my younger brother, Leif. About my husband, Paul, and about my mother’s parents and sister, who lived a thousand miles away. What they would say when they knew. How they would cry. My prayer was different now: A year, a year, a year . Those two words beat like a heart in my chest.

That’s how long my mother would live.

“What are you thinking about?” I asked her. There was a song coming over the waiting room speakers. A song without words, but my mother knew the words anyway and instead of answering my question she sang them softly to me. “Paper roses, paper roses, oh how real those roses seemed to be,” she sang. She put her hand on mine and said, “I used to listen to that song when I was young. It’s funny to think of that. To think about listening to the same song now. I would’ve never known.”

My mother’s name was called then: her prescriptions were ready.

“Go get them for me,” she said. “Tell them who you are. Tell them you’re my daughter.”

I was her daughter, but more. I was Karen, Cheryl, Leif. Karen Cheryl Leif. KarenCherylLeif. Our names blurred into one in my mother’s mouth all my life. She whispered it and hollered it, hissed it and crooned it. We were her kids, her comrades, the end of her and the beginning. We took turns riding shotgun with her in the car. “Do I love you this much?” she’d ask us, holding her hands six inches apart. “No,” we’d say, with sly smiles. “Do I love you this much?” she’d ask again, and on and on and on, each time moving her hands farther apart. But she would never get there, no matter how wide she stretched her arms. The amount that she loved us was beyond her reach. It could not be quantified or contained. It was the ten thousand named things in the Tao Te Ching’s universe and then ten thousand more. Her love was full-throated and all-encompassing and unadorned. Every day she blew through her entire reserve.

She grew up an army brat and Catholic. She lived in five different states and two countries before she was fifteen. She loved horses and Hank Williams and had a best friend named Babs. Nineteen and pregnant, she married my father. Three days later, he knocked her around the room. She left and came back. Left and came back. She would not put up with it, but she did. He broke her nose. He broke her dishes. He skinned her knees dragging her down a sidewalk in broad daylight by her hair. But he didn’t break her. By twenty-eight she managed to leave him for the last time.

She was alone, with KarenCherylLeif riding shotgun in her car.

By then we lived in a small town an hour outside of Minneapolis in a series of apartment complexes with deceptively upscale names: Mill Pond and Barbary Knoll, Tree Loft and Lake Grace Manor. She had one job, then another. She waited tables at a place called the Norseman and then a place called Infinity, where her uniform was a black T-shirt that said GO FOR IT in rainbow glitter across her chest. She worked the day shift at a factory that manufactured plastic containers capable of holding highly corrosive chemicals and brought the rejects home. Trays and boxes that had been cracked or clipped or misaligned in the machine. We made them into toys — beds for our dolls, ramps for our cars. She worked and worked and worked, and still we were poor. We received government cheese and powdered milk, food stamps and medical assistance cards, and free presents from do-gooders at Christmastime. We played tag and red light green light and charades by the apartment mailboxes that you could open only with a key, waiting for checks to arrive.

“We aren’t poor,” my mother said, again and again. “Because we’re rich in love.” She would mix food coloring into sugar water and pretend with us that it was a special drink. Sarsaparilla or Orange Crush or lemonade. She’d ask, Would you like another drink, madam? in a snooty British voice that made us laugh every time. She would spread her arms wide and ask us how much and there would never be an end to the game. She loved us more than all the named things in the world. She was optimistic and serene, except a few times when she lost her temper and spanked us with a wooden spoon. Or the one time when she screamed FUCK and broke down crying because we wouldn’t clean our room. She was kindhearted and forgiving, generous and naïve. She dated men with names like Killer and Doobie and Motorcycle Dan and one guy named Victor who liked to downhill ski. They would give us five-dollar bills to buy candy from the store so they could be alone in the apartment with our mom.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Wild»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Wild» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Wild» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.