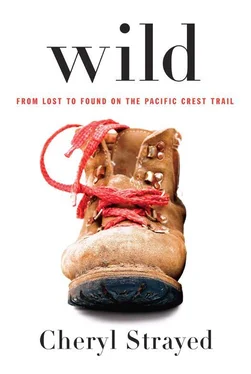

Cheryl Strayed - Wild

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cheryl Strayed - Wild» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Wild

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:978-0-307-95765-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wild: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Wild»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Wild — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Wild», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

After I hiked away from the springs that morning, fully loaded down with 24.5 pounds of water again, I realized I was having a kind of strange, abstract, retrospective fun. In moments among my various agonies, I noticed the beauty that surrounded me, the wonder of things both small and large: the color of a desert flower that brushed against me on the trail or the grand sweep of the sky as the sun faded over the mountains. I was in the midst of such a reverie when I skidded on pebbles and fell, landing on the hard trail facedown with a force that took my breath away. I lay unmoving for a good minute, from both the searing pain in my leg and the colossal weight on my back, which pinned me to the ground. When I crawled out from beneath my pack and assessed the damage, I saw that a gash in my shin was seeping copious blood, a knot the size of a fist already forming beneath the gash. I poured a tiny bit of my precious water over it, flicking the dirt and pebbles out the best I could, then pressed a lump of gauze against it until the bleeding slowed and I limped on.

I walked the rest of the afternoon with my eyes fixed on the trail immediately in front of me, afraid I’d lose my footing again and fall. It was then that I spotted what I’d searched for days before: mountain lion tracks. It had walked along the trail not long before me in the same direction as I was walking — its paw prints clearly legible in the dirt for a quarter mile. I stopped every few minutes to look around. Aside from small patches of green, the landscape was mostly a range of blonds and browns, the same colors as a mountain lion. I walked on, thinking about the newspaper article I’d recently come across about three women in California — each one had been killed by a mountain lion on separate occasions over the past year — and about all those nature shows I’d watched as a kid in which the predators go after the one they judge to be the weakest in the pack. There was no question that was me: the one most likely to be ripped limb from limb. I sang aloud the little songs that came into my head—“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” and “Take Me Home, Country Roads”—hoping that my terrified voice would scare the lion away, while at the same time fearing it would alert her to my presence, as if the blood crusted on my leg and the days-old stench of my body weren’t enough to lure her.

As I scrutinized the land, I realized that I’d come far enough by now that the terrain had begun to change. The landscape around me was still arid, dominated by the same chaparral and sagebrush as it had been all along, but now the Joshua trees that defined the Mojave Desert appeared only sporadically. More common were the juniper trees, piñon pines, and scrub oaks. Occasionally, I passed through shady meadows thick with grass. The grass and the reasonably large trees were a comfort to me. They suggested water and life. They intimated that I could do this.

Until, that is, a tree stopped me in my path. It had fallen across the trail, its thick trunk held aloft by branches just low enough that I couldn’t pass beneath, yet so high that climbing over it was impossible, especially given the weight of my pack. Walking around it was also out of the question: the trail dropped off too steeply on one side and the brush was too dense on the other. I stood for a long while, trying to map out a way past the tree. I had to do it, no matter how impossible it seemed. It was either that or turn around and go back to the motel in Mojave. I thought of my little eighteen-dollar room with a deep swooning desire, the yearning to return to it flooding my body. I backed up to the tree, unbuckled my pack, and pushed it up and over its rough trunk, doing my best to drop it over the other side without letting it fall so hard on the ground that my dromedary bag would pop from the impact. Then I climbed over the tree after it, scraping my hands that were already tender from my fall. In the next mile I encountered three other blown-down trees. By the time I made it past them all, the scab on my shin had torn open and was bleeding anew.

On the afternoon of the fifth day, as I made my way along a narrow and steep stretch of trail, I looked up to see an enormous brown horned animal charging at me.

“Moose!” I hollered, though I knew that it wasn’t a moose. In the panic of the moment, my mind couldn’t wrap around what I was seeing and a moose was the closest thing to it. “Moose!” I hollered more desperately as it neared. I scrambled into the manzanitas and scrub oaks that bordered the trail, pulling myself into their sharp branches as best I could, stymied by the weight of my pack.

As I did this, the species of the beast came to me and I understood that I was about to be mauled by a Texas longhorn bull.

“Mooooose!” I shouted louder as I grabbed for the yellow cord tied to the frame of my pack that held the world’s loudest whistle. I found it, brought it to my lips, closed my eyes, and blew with all my might, until I had to stop to get a breath of air.

When I opened my eyes, the bull was gone.

So was all the skin on the top of my right index finger, scraped off on the manzanitas’ jagged branches in my frenzy.

The thing about hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, the thing that was so profound to me that summer — and yet also, like most things, so very simple — was how few choices I had and how often I had to do the thing I least wanted to do. How there was no escape or denial. No numbing it down with a martini or covering it up with a roll in the hay. As I clung to the chaparral that day, attempting to patch up my bleeding finger, terrified by every sound that the bull was coming back, I considered my options. There were only two and they were essentially the same. I could go back in the direction I had come from, or I could go forward in the direction I intended to go. The bull, I acknowledged grimly, could be in either direction, since I hadn’t seen where he’d run once I closed my eyes. I could only choose between the bull that would take me back and the bull that would take me forward.

And so I walked on.

It took all I had to cover nine miles a day. To cover nine miles a day was a physical achievement far beyond anything I’d ever done. Every part of my body hurt. Except my heart. I saw no one, but, strange as it was, I missed no one. I longed for nothing but food and water and to be able to put my backpack down. I kept carrying my backpack anyway. Up and down and around the dry mountains, where Jeffrey pines and black oaks lined the trail, crossing jeep roads that bore the tracks of big trucks, though none were in sight.

On the morning of the eighth day I got hungry and dumped all my food out on the ground to assess the situation, my desire for a hot meal suddenly fierce. Even in my exhausted, appetite-suppressed state, by then I’d eaten most of what I didn’t have to cook — my granola and nuts, my dried fruit and turkey and tuna jerky, my protein bars and chocolate and Better Than Milk powder. Most of the food I had left needed to be cooked and I had no working stove. I didn’t have a resupply box waiting for me until I reached Kennedy Meadows, 135 trail miles into my journey. A well-seasoned hiker would have traversed those 135 miles in the time I’d been on the trail. At the rate I was moving, I wasn’t even halfway there. And even if I did make it through to Kennedy Meadows on the food I had, I still needed to have my stove repaired and filled with the proper fuel — and Kennedy Meadows, being more of a high-elevation base for hunters and hikers and fishers than a town, was no place to do it. As I sat in the dirt, ziplock bags of dehydrated food that I couldn’t cook scattered all around me, I decided to veer off the trail. Not far from where I sat, the PCT crossed a network of jeep roads that ran in various directions.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Wild»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Wild» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Wild» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.