Fig. 1: Bruegel the Elder, “The Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind” (1568) — Museo di Capodimonte, Naples. (“Herbst picked up the picture and stood it up so he could see it better. The eyes were awesome and sad. Their sockets had, for the most part, been consumed by leprosy, yet they were alive and wished to live.”)

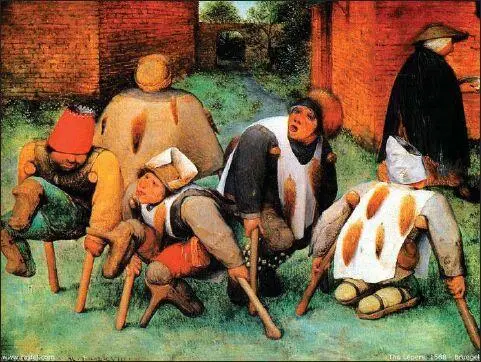

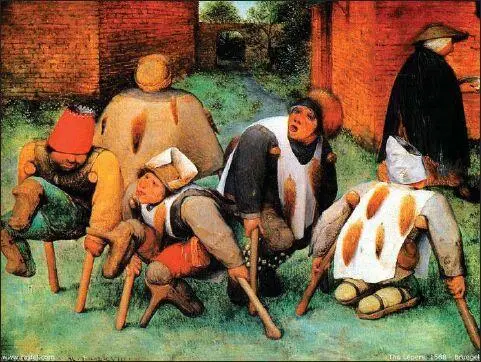

Fig. 2: Bruegel the Elder, “The Lepers” (aka “The Cripples”) (1568) — The Louvre, Paris

Fig. 3: Bruegel the Elder, Detail of “The Fight of Carnival and Lent” (1559) — Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Fig. 4: Rembrandt, “The Night Watch” (1642) — Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Fig. 5: Rembrandt, “The Anatomy Lesson” (1632) — Mauritshuis, The Hague

Fig. 6: Arnold Böcklin, “The Isle of the Dead” (1883) — Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Fig. 7: Arnold Böcklin, “The Plague” (1898) — Kunstmuseum, Basel

Fig. 8: Arnold Böcklin, “Self-Portrait with Death as a Fiddler” (1872) — Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Seeking relief from the terrible intensity of the Bruegelian painting, Herbst flips through a stack of Rembrandt reproductions and comes to The Night Watch [Fig. 4], on which he dwells. Rembrandt would seem to present a kind of art antithetical to that of the anonymous painter from the school of Bruegel. The narrator tells us that Herbst now experiences a sense of melancholy accompanied by “inner tranquility” ( menuhat hanefesh , literally, “soul’s rest”), a tranquility usually identified as harmony but which he, the narrator, prefers to associate with the illumination of knowledge. The opposition, however, between Rembrandtian and Bruegelian art rapidly dissolves, like most of the key oppositions in the novel. To begin with, The Night Watch immediately makes Herbst think of Shira, who had been looking for a reproduction of the painting, and she is doubly associated with disease — the wasting disease that by this point we suspect she has contracted, and her hapless lover’s disease of the spirit manifested in his obsessive relationship with her. But a few minutes later in narrated time, Herbst suddenly realizes that his memory has played a trick on him, or, in the psychoanalytic terms never far from Agnon’s way of conceiving things from the thirties onward, he has temporarily repressed something. It was not The Night Watch , with its beautifully composed sense of confident procession, that Shira wanted, but another Rembrandt painting, The Anatomy Lesson [Fig. 5]. The clinical subject of the latter painting might of course have a certain professional appeal to Shira as a nurse, but what is more important is that its central subject is not living men marching but a cadaver, and thus it is linked with the representation of the living-dead leper in the anonymous canvas.

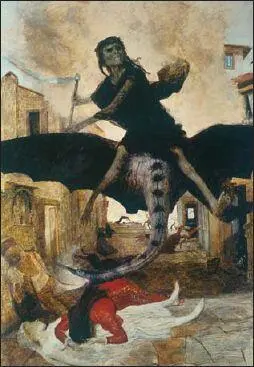

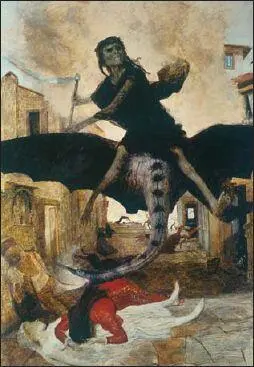

Death as a subject, in turn, connects Rembrandt with Böcklin, the artist responsible for the painting of the death’s-head that Shira keeps in her apartment. Arnold Böcklin, a Swiss painter much in fashion in Central Europe toward the end of the nineteenth century (Stefan George wrote a poem about him), provides one of the teasing keys to Shira . Böcklin had a pronounced preference for mythological and allegorical topics, often rendered with a sharp realism of detail, and in pursuing this interest he repeatedly devoted emphatic attention to those figures of classical mythology associated with a riot of sensuality — Pan, satyrs, centaurs, Triton disporting himself with a Nereid. He also produced two versions of an allegorical painting that is particularly pertinent to the central thematic complex of Shira : entitled Poetry and Painting , it shows two female figures on either side of a fountain (presumably, the Pierian Spring), Poetry on the left, naked to the waist, leaning on the fountain’s edge; Painting on the right, enveloped in drapery, dipping one hand into the water while with the other she holds a palette. Interestingly, Böcklin never did a painting of a skull, if one can trust the testimony of the comprehensive illustrated catalogue of his paintings published in Berne in 1977. He was, however, much preoccupied with death, which he characteristically represented in a histrionic mode that has a strong affinity with Symbolist painting. One scene he painted a few times was The Isle of the Dead [Fig. 6], in which the island looms as a spooky vertical mass against a dark background, with a small boat approaching it in the foreground, rowed by a presumably male figure, his back to us, while a female figure in white stands erect in the boat. One of his last paintings, The Plague (1898) [Fig. 7], exhibits a more brutally direct relevance to Shira : a hideous female figure, with large wings and grotesque tail, yet more woman than monster, swoops down over the streets of a town.

The reproduction that hangs on Shira’s wall is probably of Self-Portrait with Death as Fiddler (1872) [Fig. 8]. It is possible that Agnon simply forgot the self-portrait and concentrated on the skull when he introduced the painting into his novel, but given his frequently calculating coyness as a writer, it seems more likely that he deliberately suppressed the entire foreground of the canvas. In the foreground, Böcklin, wearing an elegant dark smock, stands with palette in one hand and brush in the other, his trim beard delicately modeled by a source of light from the upper left, his lively lucid eyes intent on the canvas he is painting. Behind him, in the upper right quadrant of the painting, virtually leaning on the painter’s back, death as a leering skull with bony hand — rendered in the same precise detail as the figure of the artist — scratches away on his fiddle. That missing artist absorbed in his work who stands in front of the figure of death is, in one respect, what Shira is all about.

Death is, I think, a specter of many faces in this somber, troubling novel. It has, to begin with, certain specific historical resonances for the period of the late 1930s in which the action is set. In the two decades since 1914, death had given ample evidence of having been instated as the regnant Zeitgeist of the century. Herbst recalls wading up to his knees in blood as a soldier in the great senseless slaughter that was the First World War. The novel begins with mention of a young man murdered by Arabs, and in these days of organized terrorist assaults and random violence against the Jews of Palestine that began in 1936, there is a repeated drumbeat of killings in the background of the main action. On the European horizon, German Jews are desperately trying to escape, many of them sensing that Germany is about to turn into a vast death-trap. But beyond Agnon’s ultimately political concern with the historical moment as a time of endemic murder, he is also gripped by the timeless allegory of Böcklin’s painting: every artist, in every age, as an ineluctable given of his mortal condition, works with death fiddling at his back, and cannot create any art meaningfully anchored in the human condition unless he makes the potency of death part of it, at once breathing life into the inanimate and incorporating death in his living creation. Agnon was nearing sixty when he began work on the novel and an octogenarian when he made his last concerted effort to finish it, and it is easy enough to imagine that he saw himself in Böcklin’s attitude as selfportraitist, the grim fiddler just behind him.

Читать дальше