“Well … all right.”

I accepted the wine list from the waiter and chose a Malbec, two glasses. When the waiter had left, Dorothy said, “I’m not very used to drinking alcohol.”

“But you’re familiar with the virtues of the Mediterranean diet, surely.”

“Yes,” she said. Her eyes narrowed.

“And I know you must have heard about olive oil.”

“Look,” she said. “Are you going to start telling me your symptoms?”

“What?”

“I’m here to discuss a book project, okay? I don’t want to check out some little freckle that might be cancer.”

“Check out what ? What freckle?”

“Or hear about some time when you thought your pulse might have skipped a beat.”

“Are you out of your mind?” I asked.

She started looking uncertain.

“My pulse is perfect!” I said. “What are you talking about?”

“Sorry,” she said.

She lowered her gaze to her place setting. She moved her spoon half an inch to her right. She said, “A lot of times, people outside of the office ask me for free advice. Even if they’re just sitting next to me on an airplane, they ask.”

“Did I ask? Did you hear me ask you anything?”

“Well, but I thought—”

“You seem to be suffering from a serious misapprehension,” I told her. “If I need advice, I’ll make an appointment with my family physician. Who is excellent, by the way, and knows my entire medical history besides, not that I ever have the slightest reason to call on him.”

“I already said I was sorry.”

She took off her glasses and polished them on her napkin, still keeping her eyes lowered. Her eyelashes were thick but very short and stubby. Her mouth was clamped in a thin, unhappy line.

I said, “Hey. Dorothy. Want to start over?”

There was a pause. I saw the corners of her lips start to twitch, and then she looked up at me and smiled.

It makes me sad now to think back on the early days of our courtship. We didn’t know anything at all. Dorothy didn’t even know it was a courtship, at the beginning, and I was kind of like an overgrown puppy, at least as I picture myself from this distance. I was romping around her all eager and panting, dying to impress her, while for some time she remained stolidly oblivious.

By that stage of life, I’d had my fair share of romances. I had left behind the high-school girls who were so fearful of seeming freakish themselves that they couldn’t afford to be seen with me, and in college I became a kind of pet project for the aspiring social workers that all the young women of college age seemed to be. They associated my cane with, who knows, old war wounds or something. They took the premature glints of white in my hair as a sign of mysterious past sufferings. As you might surmise, I had an allergy to this viewpoint, but usually at the outset I didn’t suspect that they held it. (Or didn’t let myself suspect.) I just gave myself over to what I fancied was true love. As soon as I grasped the situation, though, I would walk out. Or sometimes they would walk out, once they lost all hope of rescuing me. Then I graduated, and in the year and a half since, I had pretty much stuck to myself, taking care to avoid the various sweet young women that my family seemed to keep strewing in my path.

You see now why I found Dorothy so appealing — Dorothy, who wouldn’t even discuss the Mediterranean diet with me.

I went to her office a few days later to tour her treatment rooms, asking what if a patient had this kind of tumor, what if a patient had that kind of tumor. I went again with a list of follow-up questions that Dr. Worth had supposedly dictated to me. And after that, of course, I had to show her my rough draft over another dinner, this time at a place with better lighting.

Then a major development: I suggested we go to a movie the following evening. An outing with no useful purpose. She had a little trouble with that one. I saw her working to make the adjustment in her mind — switching me from “business” to “pleasure.” She said, “I don’t know,” and then she said, “What movie were you thinking of?”

“Whichever one you like,” I told her. “I would let you choose.”

“Well,” she said. “Okay. I don’t have anything better to do.”

We went to the movie — a documentary, as I recall — and then, a few days later, we went to another one, and after that to a couple more meals. We talked about her work, and my work, and the news on TV, and the books we were reading. (She read seriously and pragmatically, always about something scientific if not specifically radiological.) We traded the usual growing-up stories. She hadn’t been back to see her family in years, she said. She seemed amused to hear that I lived in an apartment only blocks away from my parents.

At that first movie I took her elbow to usher her into her seat, and at the second I sat with my shoulder touching hers. Leaning across the table to make a point to her over dinner, I covered her hand with mine; parting at the end of each evening, I began giving her a brief hug — but no more of a hug than I might give a friend. Oh, I was cagey, all right. I didn’t completely understand her; I couldn’t read her feelings. And already I knew that this was too important for me to risk any missteps.

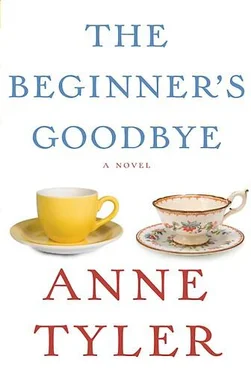

In April I brought her a copy of The Beginner’s Income Tax , which was not really about taxes but about organizing receipts and such. She was hopelessly disorganized, she claimed; and then, as if to prove it, she forgot to take the book with her when we left the restaurant. I worried about what this meant. I felt she had forgotten me —easy come, easy go, she was saying — and it didn’t help that when I offered to turn the car around that minute and go retrieve it, she said never mind, she would just phone the restaurant later.

Did she care about me even a little?

Then she asked why I didn’t have a handicapped license plate. We were walking toward my car at the time; we’d been to the Everyman Theatre. I said, “Because I don’t need a handicapped license plate.”

“You’re bound to throw your back out of whack, walking the distances you do with that limp. I’m surprised it hasn’t already happened.”

I said nothing.

“Would you like me to fill in a form for the Motor Vehicle people?”

“No, thanks,” I said.

“Or maybe you’d prefer a hang-tag. Then we could switch it to my car if I were the one driving.”

“I told you, no,” I said.

She fell silent. We got into the car and I drove her home. By this time I knew where she lived — a basement apartment down near the old stadium — but I hadn’t been inside, and I had planned to suggest that evening that I come in with her. I didn’t, though. I said, “Well, good night,” and I reached across her to open her door.

She looked at me for a moment, and then she said, “Thank you, Aaron,” and got out. I waited till she was safely in her building and then I drove away. I was feeling kind of depressed, to be honest. I don’t mean I’d fallen out of love with her or anything like that, but I felt very low, all at once. Very tired. I felt weary to the bone.

Pursuing the theme of let’s-see-each-other’s-apartments, I had planned next to invite her to supper at my place. I was thinking I would fix her my famous spaghetti and meatballs. But now I put that off a few days, because it seemed like so much trouble. I would have to get that special mix of different ground meats, for one thing. Veal and so on. Pork. I didn’t trust an ordinary supermarket for that; I’d have to go to the butcher. It seemed a huge amount of effort for a dish that was really, when you came down to it, not all that distinctive.

Читать дальше