Right now? Only a few miles! Nude beliefs, here we come!

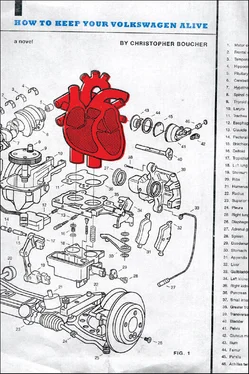

Loveis measured in Gauge Twenty—specifically, love pressure (LP) in the surrounding area. It’s normal for the gauge to read anywhere from ten to twenty percent. If it drops below four percent, though, you may have trouble — the VW may get sad, slow down or even stop altogether. If this occurs, you have to immediately find/write a story that somehow convinces him that there is more love, caring or compassion in the area than he thinks there is. I can’t tell you how many times this has been a problem for us — how many trips were interrupted because I had to head into the nearest populated town to see if we could find some examples of kindness. Sometimes it just wasn’t there for us to find, and in those cases I’d have to sit down and try to write something — type into the book of power, print out the sheet, feed it manually. I don’t think that approach ever actually yielded more LP, but I just couldn’t think of anything else to do.

SIGNALS/DIRECTIONALS

Once you know the basics (how to accelerate, stop, steer) you can really go anywhere you want to: backwards, forwards, to one side or another. It’s important to remember, though, that you’re not the only car on the road, and that everyone around you — the other drivers, houses and businesses, streets and gutters, western Massachusetts itself! — needs to know which direction you’re heading. Are you vaulting back into what was? Turning to one future or another? Taking Memorial Drive? You can avoid costly book-benders and collisions by signaling your intent.

The good news, though, is that signaling is easy: Just hold out your left arm and point it skywards if you’re reading to the right, or straight out to the left if you’re reading to the left.

Let’s try it. First, decide which way you intend to read.

Now, signal with your left arm.

Raise your arm higher — I can barely see it.

Yes! Now I know: You’re reading to the right.

Remember, too, that you’re not the only one out there sending signals. Everyone and everything that you see is maintaining an image of some sort, some picture of themselves purveyed. Signaling, then, is not just choosing any old direction — it’s every message you send. It’s how you walk and how you look, and it’s choosing a face —the face of a quiet reader, the face of an angry son, the face of the Longmeadow Dump. Be mindful of the signal that you’re sending, and don’t be afraid to let it change as you change. It is meaningful to meet a tunnel, fall in love with it, take it home and faith. But remember that the tunnel — like you, like me — is actually a signal for something else. You might go to bed entrenched and wake up to a broom or a puddle of water.

I realize this is frustrating. It’s what we’re trying to stop!

THE STORY

As always, there is a story — the tale, in this case, of you or me driving a Volkswagen Beetle.

I didn’t want to use the VW as my main means of transportation, but when the Lady from the Land of the Beans left me I had no choice — she’d taken the VeggieCar and I needed a way to get to work and around town. What else could I do? I had not a minute to spare, and every job that I could think of required me to have a car.

And it’s not like I had to teach him; the VW knew everything he needed to already. He’d already practiced turns and maneuvers in the big driveway behind our house, and his teachers at school used to tell me that he’d spend his time during recess showing off his three-point turns on the playground. I was the one who needed the practice, and so every day for two weeks the VW and I went out for drives. I’d practice stops and starts on Crescent Street, then lag onto Routes 9 or 5 and rehearse accelerations, shifts and page-turns until I finally felt I could control the car.

But learning to drive the VW wasn’t a smooth process; in fact, we fought almost every time we practiced. I’d get angry at the VW for speeding or traveling too many lines at one time, or he’d groan about how slow I was going or the fact that we traveled the same roads over and over.

And while the VW knew how to maneuver himself on the road, he didn’t understand the first thing about western Massachusetts — its stops of story and memory and fear. I scolded him repeatedly for driving too casually, for not staying aware. One fall afternoon, while driving through Florence, I tried to elaborate. “There are roads that we can take and roads we can’t,” I explained.

“Why not?”

“Because people go down those roads and they don’t come back,” I said.

“Ever?”

“Right,” I said.

The VW was quiet for a moment. “Well, how do we know which roads are OK?”

“I’m writing about that in the power,” I told him. “The first rule, though, is to follow your ears, your heart.”

The Volkswagen spoke slowly. “Follow my ears—”

“Well, your sensors.”

“—and my heart.”

“Your engineheart,” I said.

“What am I listening for ?”

“For change — the sound or sign of change. That’s why you need to avoid the main routes. Forty-seven is OK, and five, but never ninety-one or ninety.”

“Why not?”

“Because you can get lost; they might take you so far away from here that you’ll— we’ll —forget which roads you took,” I said. “Or, Northampton could change its tune while you’re driving, seal off its exit, and then you’re screwed.”

The VW seemed to be digesting this. “Why can other cars—”

“You’re not like other cars,” I told him. “They’re searching for something. You already have everything you need.”

How could I know at the time how true those words were?

Even so, though, the VW heard but didn’t listen . He was always getting lost or distracted by something on the side of the road, and the older he got the more curious he became and the harder it became for me to drive him. He’d make decisions without asking me, take turns without even signaling. Once, driving towards Hadley, he saw an entrance to Route 91 and he leaned towards it as if I wouldn’t notice.

“Hey,” I said, grabbing the wheel.

He didn’t say anything. He just kept leaning.

“VW,” I said again. I yanked the steering wheel over. “What are you doing?”

The VW spat oil.

“What’s the rule about ninety-one?” I said.

“Even though there are a million freaking cars on it.”

“ They aren’t you,” I said.

“You mean they aren’t sick ?”

“You aren’t sick,” I said. “You just don’t understand—”

“—understand the area. I know.”

“You don’t,” I said. “These towns can be loud and harsh.”

“Sure they can,” the VW curred.

“Alright big shot — what do you do when you meet a city made of parchment?”

The VW’s eyes went off. “There are cities made of parchment?”

“Off ninety-one? Absolutely. Parts of Amherst are paper-thin. Not only that, I’ve seen towns made of prayer — heard of others made of fabric and film.”

I could hear the VW processing this. “But how do I navigate—”

“You don’t. You stay off ninety-one, away from the changes.”

The VW made a gutterface. “Away from the changes,” he sang, impersonating me.

“Hey — stop that.”

“Stop that,” the VW said, his voice high and thin.

“I wonder what a good memory coil would go for at the flee bee,” I said.

The VW smiled and slowed down. “You wouldn’t do that,” he said.

“You never know,” I said.

Читать дальше