It always feels worse than it looks, he will comfort himself, feeling its enormity; say to himself, the tactual never corresponds with the appearance of such a blemish, and dismiss it. I shall allow my eyes at strategic moments to explore his face then settle to revive the gnathic discomfort.

Somewhere at the back of the house Moira’s voice has been rising and falling, flashing familiar stills from the past. Will she be as nervous as I am? A door clicks and a voice starts up again, closer, already addressing me, so that the figure develops slowly, fuzzily assumes form before she appears: ‘. to deal with these people and I just had to be rude and say my friend’s here, all the way from England, she’s waiting. ’

Standing in the doorway, she shakes her head. ‘My God Frieda Shenton, you plaasjapie, is it really you?’

I grin. Will we embrace? Shake hands? My arm hangs foolishly. Then she puts her hands on my shoulders and says, ‘It’s all my fault. I’m hopeless at writing letters and we moved around so much and what with my hands full with children I lost touch with everyone. But I’ve thought of you, many a day have I thought of you.’

‘Oh nonsense,’ I say awkwardly. ‘I’m no good at writing letters either. We’ve both been very bad.’

Her laughter deals swiftly with the layer of dust on that old intimacy but our speech, like the short letters we exchanged, is awkward. We cannot tumble into the present while a decade gapes between us.

Sitting before her I realise what had bothered me yesterday on the telephone when she said, ‘Good heavens man I can’t believe it. Yes of course I’ve remembered. OK, let me pick you up at the station.’

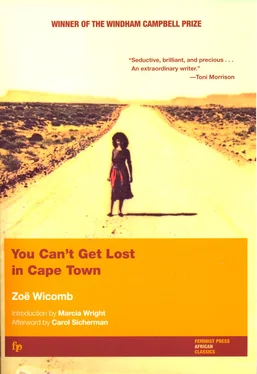

Unease at what I now know to be the voice made me decline. ‘No,’ I said. ‘I’d like to walk, get to see the place. I can’t get enough of Cape Town,’ I gushed. For her voice is deeper, slowed down eerily like the distortion of a faulty record player. Some would say the voice of a woman speaking evenly, avoiding inflection.

‘I bet,’ she says, ‘you regretted having to walk all that way.’

She is right. The even-numbered houses on the left side of this interminable street are L-shaped with grey asbestos roofs. Their stoeps alternate green, red and black, making spurious claims to individuality. The macadamised street is very black and sticky under the soles, its concrete edge of raised pavement a virgin grey that invites you to scribble something rude, or just anything at all. For all its neat edges, the garden sand spills on to the pavement as if the earth were wriggling in discomfort. It is the pale porous sand of the Cape Flats pushed out over centuries by the Indian Ocean. It does not portend well for the cultivation of prizewinning dahlias.

I was so sure that it was Moira’s house. There it was, a black stoep inevitably after the green, the house inadequately fenced off so that the garden sand had been swept along the pavement in delicately waved watermark by the previous afternoon’s wind. A child’s bucket and spade had been left in the garden and on a mound of sand a jaunty strip of astroturf testified to the untameable. I knocked without checking the number again and felt foolish as the occupier with hands on her hips directed me to the fourth house along.

Moira’s is a house like all the others except for the determined effort in the garden. Young trees grow in bonsai uniformity, promising a dense hedge all around for those who are prepared to wait. The fence is efficient. The sand does not escape; it is held by the roots of a brave lawn visibly knitting beneath its coarse blades of grass. Number 288 is swathed in lace curtains. Even the glass-panelled front door has generously ruched lengths of lace between the wooden strips. Dense, so that you could not begin to guess at the outline approaching the door. It was Desmond.

‘Goodness me, ten, no twelve years haven’t done much to damage you,’ Moira says generously.

Think so Moi,’ Desmond adds. ‘I think Frieda has a contract with time. Look, she’s even developed a waistline,’ and his hands hover as if to describe the chimerical curve. There is the possibility that I may be doing him an injustice.

‘I suppose it’s marriage that’s done it for us. Very ageing, and of course the children don’t help,’ he says.

‘It’s not a week since I sewed up this cushion. What do the children do with them?’ Moira tugs at the loose threads then picks up another cushion to check the stitching.

‘See,’ Desmond persists, ‘a good figure in your youth is no guarantee against childbearing. There are veins and sagging breasts and of course some women get horribly fat; that is if they don’t grow thin and haggard.’ He looks sympathetically at Moira. Why does she not spit in his eye? I fix my eye on his jaw so that he says, ‘Count yourself lucky that you’ve missed the boat.’

Silence. And then we laugh. Under Desmond’s stern eye we lean back in simultaneous laughter that cleaves through the years to where we sat on our twin beds recounting the events of our nights out. Stomach-clutching laughter as we whispered our adventures and decoded for each other the words grunted by boys through the smoke of the braaivleis. Or the tears, the stifled sobs of bruised love, quietly, in order not to disturb her parents. She slept lightly, Moira’s mother, who said that a girl cannot keep the loss of her virginity a secret, that her very gait proclaims it to the world and especially to men who will expect favours from her.

When our laughter subsides Desmond gets a bottle of whisky from the cabinet of the same oppressively carved dark wood as the rest of the sitting-room suite.

‘Tell Susie to make some tea,’ he says.

‘It’s her afternoon off. Eh. ’ Moira’s silence asserts itself as her own so that we wait and wait until she explains, ‘We have a servant. People don’t have servants in England, do they? Not ordinary people, I mean.’

‘It’s a matter of nomenclature I think. The middle classes have cleaning ladies, a Mrs Thing, usually quite a character, whom we pretend to be in awe of. She does for those of us who are too sensitive or too important or intelligent to clean up our own mess. We pay a decent wage, that is for a cleaner, of course, and not to be compared with our own salaries.’

Moira bends closely over a cushion, then looks up at me and I recall a photograph of her in an op-art mini-skirt, dangling very large black and white earrings from delicate lobes. The face is lifted quizzically at the photographer, almost in disbelief, and her cupped hand is caught in movement perhaps on the way to check the jaunty flick-ups. I cannot remember who took the photograph but at the bottom of the picture I recognise the intrusion of my right foot, a thick ankle growing out of an absurdly delicate high-heeled shoe.

I wish I could fill the ensuing silence with something conciliatory, no something that will erase what I have said, but my trapped thoughts blunder insect-like against a glazed window. I who in this strange house in a new Coloured suburb have just accused and criticised my hostess. She will have seen through the deception of the first-person usage; she will shrink from the self-righteousness of my words and lift her face quizzically at my contempt. I feel the dampness crawl along my hairline. But Moira looks at me serenely while Desmond frowns. Then she moves as if to rise.

‘Don’t bother with tea on my account,’ I say with my eye longingly on the whisky, and carry on in the same breath, ‘Are you still in touch with Martin? I wouldn’t mind seeing him after all these years.’

Moira’s admirers were plentiful and she generously shared with me the benefits of her beauty. At parties young men straightened their jackets and stepped over to ask me to dance. Their cool hands fell on my shoulders, bare and damp with sweat. I glided past the rows of girls waiting to be chosen. So they tested their charm — ‘Can I get you a lemonade? Shall we dance again?’ — on me the intermediary. In the airless room my limbs obeyed the inexorable sweep of the ballroom dances. But with the wilder Twist or Shake my broad shoulders buckled under a young man’s gaze and my feet grew leaden as I waited for the casual enquiry after Moira. Then we would sit out a dance chatting about Moira and the gardenia on my bosom meshed in maddening fragrance our common interest. My hand squeezed in gratitude with a quick goodnight, for there was no question about it: my friendship had to be secured in order to be considered by Moira. Then in the early hours, sitting cross-legged on her bed, we sifted his words and Moira unpinned for me the gardenia, crushed by his fervour, when his cool hand on my shoulder drew me closer, closer in that first held dance.

Читать дальше