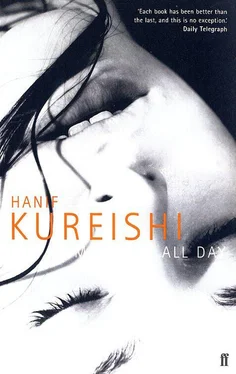

Hanif Kureishi - Midnight All Day

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Hanif Kureishi - Midnight All Day» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2006, Издательство: Faber & Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Midnight All Day

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber & Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Midnight All Day: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Midnight All Day»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Midnight All Day — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Midnight All Day», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was cold when they got down. The wind cut across the open spaces. Already it seemed to be getting dark. They walked further than he’d imagined they would have to, and across muddy patches. He complained that she should have told him to wear different shoes.

He suggested they take something for her mother. He could be very polite. He even said ‘excuse me’ in bed if he made an abrupt movement. They went into a brightly lit supermarket and asked for flowers; there were none. He asked for lapsang souchong teabags, but before the assistant could reply, Nicole pulled him out.

The area was sombre but not grim, though a swastika had been painted on a fence. Her mother’s house was set on a grassy bank, in a sixties estate, with a view of a park. As they approached, Nicole’s feet seemed to drag. Finally she halted and opened her coat.

‘Put your arms around me.’ He felt her shivering. She said, ‘I can’t go in unless you say you love me.’

‘I love you‚’ he said, holding her. ‘Marry me.’

She was kissing his forehead, eyes, mouth. ‘No one has ever cared for me like you.’

He repeated, ‘Marry me. Say you will, say it.’

‘Oh I don’t know‚’ she replied.

She crossed the garden and tapped on the window. Immediately her mother came to the door. The hall was narrow. The mother kissed her daughter, and then Majid, on the cheek.

‘I’m pleased to see you‚’ she said, shyly. She didn’t appear to have been drinking. She looked Majid over and said, ‘Do you want a tour?’ She seemed to expect it.

‘That would be lovely‚’ he said.

Downstairs the rooms were square, painted white but otherwise bare. The ceilings were low, the carpet thick and green. A brown three-piece suite — each item seemed to resemble a boat — was set in front of the television.

Nicole was eager to take Majid upstairs. She led him through the rooms which had been the setting for the stories she’d told. He tried to imagine the scenes. But the bedrooms that had once been inhabited by lodgers — van drivers, removal men, postmen, labourers — were empty. The wallpaper was gouged and discoloured, the curtains hadn’t been washed for a decade, nor the windows cleaned; rotten mattresses were parked against the walls. In the hall the floorboards were bare, with nails sticking out of them. What to her reverberated with remembered life was squalor to him.

As her mother poured juice for them, her hands shook, and it splashed on the table.

‘It’s very quiet‚’ he said, to the mother. ‘What do you do with yourself all day?’

She looked perplexed but thought for a few moments.

‘I don’t really know‚’ she said. ‘What does anyone do? I used to cook for the men but running around after them got me down.’

Nicole got up and went out of the room. There was a silence. Her mother was watching him. He noticed that there appeared to be purplish bruises under her skin.

She said, ‘Do you care about her?’

He liked the question.

‘Very much‚’ he said. ‘Do you?’

She looked down. She said, ‘Will you look after her?’

‘Yes. I promise.’

She nodded. ‘That’s all I wanted to know. I’ll make your dinner.’

While she cooked, Nicole and Majid waited in the lounge. He said that, like him, she seemed only to sit on the edge of the furniture. She sat back self-consciously. He started to pace about, full of things to say.

Her mother was intelligent and dignified, he said, which must have been where Nicole inherited her grace. But the place, though it wasn’t sordid, was desolate.

‘Sordid? Desolate? Not so loud! What are you talking about?’

‘You said your mother was selfish. That she always put herself, and her men friends in particular, before her children.’

‘I did say —’

‘Well, I had been expecting a woman who cosseted herself. But I’ve never been in a colder house.’ He indicated the room. ‘No mementos, no family photographs, not one picture. Everything personal has been erased. There is nothing she has made, or chosen to reflect —’

‘You only do what interests you‚’ Nicole said. ‘You work, sit on boards, eat, travel and talk. “Only do what gives you pleasure,” you say to me constantly.’

‘I’m a sixties kid‚’ he said. ‘It was a romantic age.’

‘Majid, the majority can’t live such luxurious lives. They never did. Your sixties is a great big myth.’

‘It isn’t the lack of opulence which disturbs me, but the poverty of imagination. It makes me think of what culture means —’

‘It means showing off and snobbery —’

‘Not that aspect of it. Or the decorative. But as indispensable human expression, as a way of saying, “Here there is pleasure, desire, life! This is what people have made!”’

He had said before that literature, indeed, all culture, was a celebration of life, if not a declaration of love for things.

‘Being here‚’ he continued, ‘it isn’t people’s greed and selfishness that surprises me. But how little people ask of life. What meagre demands they make, and the trouble they go to, to curb their hunger for experience.’

‘It might surprise you‚’ she said, ‘because you know successful egotistical people who do what they love. But most people don’t do much of anything most of the time. They only want to get by another day.’

‘Is that so?’ He thought about this and said that every day he awoke ebulliently and full of schemes. There was a lot he wanted, of the world and of other people. He added, ‘And of you.’

But he understood sterility because despite all the ‘culture’ he and his second wife had shared, his six years with her had been arid. Now he had this love, and he knew it was love because of the bleakness that preceded it, which had enabled him to see what was possible.

She kissed him. ‘Precious, precious‚’ she said.

She pointed to the bolted door she had mentioned to him.She wanted to go downstairs. But her mother was calling them.

They sat down in the kitchen, where two places had been laid. Nicole and her mother saw him looking at the food.

‘Seems a bit funny giving Indian food to an Indian‚’ the mother said. ‘I didn’t know what you eat.’

‘That’s all right‚’ he said.

She added, ‘I thought you’d be more Indian, like.’

He waggled his head. ‘I’ll try to be.’ There was a silence. He said to her, ‘It was my birthday yesterday.’

‘Really?’ said the mother.

She and her daughter looked at one another and laughed.

While he and Nicole ate, the mother, who was very thin, sat and smoked. Sometimes she seemed to be watching them and other times fell into a kind of reverie. She was even-tempered and seemed prepared to sit there all day. He found himself seeking the fury in her, but she looked more resigned than anything, reminding him of himself in certain moods: without hope or desire, all curiosity suppressed in the gloom and agitated muddle of her mind.

After a time she said to Nicole, ‘What are you doing with yourself? How’s work?’

‘Work? I’ve given up the job. Didn’t I tell you?’

‘At the television programme?’

‘Yes.’

‘What for? It was a lovely job!’

Nicole said, ‘It wore me out for nothing. I’m getting the strength to do what I want, not what I think I ought to do.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’ her mother said. ‘You stay in bed all day?’

‘We only do that sometimes‚’ Majid murmured.

Her mother said, ‘I can’t believe you gave up such a job! I can’t even get work in a shop. They said I wasn’t experienced enough. I said, what experience do you need to sell bread rolls?’

In a low voice Nicole talked of what she’d been promising herself — to draw, dance, study philosophy, get healthy. She would follow what interested her. Then she caught his eye, having been reminded of one of the strange theories that puzzled and alarmed her. He maintained that it wasn’t teaching she craved, but a teacher, someone to help and guide her; perhaps a kind of husband. She found herself smiling at how he brought everything back to them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Midnight All Day»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Midnight All Day» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Midnight All Day» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.