Heart swollen with anticipation, Iphigenia steps onto the rocky shore from her father Agamemnon's ship and immediately feels she has done this before. Gnarled graygreen cypress trees spattered here and there. The sky a violent blue. How the flock of white birds gyre above her like a flock of silent white hands.

She pauses to take in the scene. Scree crunches beneath her sandals. Iphigenia is in Aulis to marry Achilles.

There is a story she has heard. In order to make her son immortal, Achilles' mother, a sea nymph, dipped him into the river Styx. The black water caught the baby's soul on fire. The fire has never gone out. To anger him is to witness uncontaminated rage. Yet the opposite is also true: to know uncontaminated rage is to know uncontaminated love. Iphigenia cannot wait to learn what such a sensation feels like. Whenever she brings up the topic with her attendants, they lower their heads, cover their mouths, and titter.

In the dining hall one evening, her father told Clytemnestra that Iphigenia would be sailing with him to Aulis the following morning. Next Iphigenia knew, she was standing on the dock, throat aching as if she were about to cry, hugging her mother goodbye, who did not hug her back, hugging her sisters, her brother. Next she knew, she was kneeling at the railing in a mad black storm on the open sea, wind and rain tearing into her, being sick. Next she knew, she was stepping onto this rocky shore, thinking: This is where I shall be wed. This is what it is like.

Her attendants flow around her, bearing crates filled with her wardrobe and jewelry, her favorite foods and favorite oils, bearing her favorite bed above their heads, her prized satin chair, her prized satin pillows. Her pet cheetah growls in a cage nearby. The townspeople have arrived at the periphery to gawk at this impromptu entertainment.

Agamemnon steps up beside his daughter and halts, huge palms on hips, surveying the disembarkation. He smells of balms and garlicky sweat. Iphigenia lets him be himself for several seconds, then asks:

When shall I meet him, Papa? Today?

Agamemnon does not take his eyes off the commotion occurring around him, the temple high on the craggy hill overlooking it all, the delicate white hands spiraling through this morning.

Behind him scores of ships, sails bloated, ease into the bay.

Soon, daughter, he says. Soon.

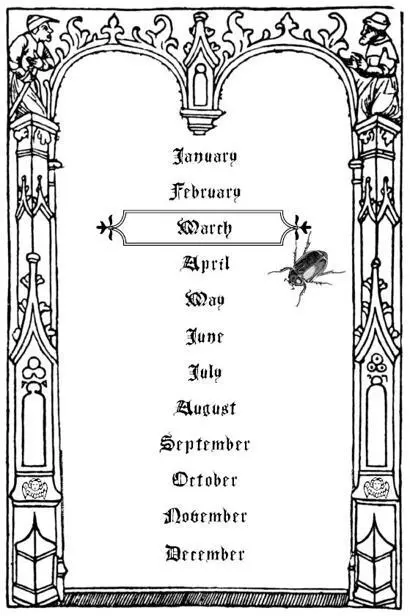

But it isn't soon. It isn't soon at all. The afternoon is a long, plodding settling in. The evening a great feast sans bridegroom, with panflute music, dwarfs in monkey outfits, the sacrifice of a colossal ox. The night a series of alarming apparitions. Ever since she can remember, Iphigenia has been visited by visions from a future that is never her future. She sees what will happen to others while remaining blind to what will happen to herself. These are Iphigenia's puzzling secrets. She keeps them private, uncut gems scooped off the packed soil of alleys among the market stalls of sleep. A large bat with Electra's face sucks on her sleeping mother's neck. The god Phantasos materializes before Orestes as an inexpensive pearl necklace, a heavy battleaxe, a beautifully crafted arrow embedded in a bloody heel, yet refuses to utter a sound. An emaciated old man, who resembles nothing so much as a frog in a funny costume reared back on its hind legs, clutches his chest in a candle-lit room and collapses. He has been holding a paintbrush. It clatters across the floorboards.

Iphigenia is thirteen, but she feels much older and wiser. She has traveled. She has seen things. She possesses a pet cheetah. She is marrying a demigod.

Surrounded by attendants in the modest temple at the top of the hill, Iphigenia prays. Offers up to the gods a piece of cloth from her most lavish childhood dress. Offers up her special childhood toy: a mechanical bird that steam makes sing and flap its wings. These items will assist Iphigenia in departing her youth, in the migration to the foreign land called adulthood.

To the goddess of virginity, Iphigenia offers up a lock of her own long glossy blueblack hair and a miniature engraved chest filled with silver coins. On one side of each coin is the image of Helios, sunrays streaming from his head. On the other is the image of her father, sharp nose, thin lips, jug-handle ears, almond-shaped eyes.

The air is tangy with incense. Behind Iphigenia's eyelids, the cosmos seems dark and damp as the back of her mouth.

Yesterday she knew how to feel and what to think.

Today she is hovering.

Iphigenia is closer to her attendant Anthea, whose prehistoric skin reminds her of an elephant's crumpled shank, than to anyone else on earth.

Anthea taps Iphigenia on the shoulder and tells her it is time to move on.

Iphigenia rises.

The procession winds its way from the temple to the women's quarters for the pine-scented nuptial bath. Ten garlanded slave girls — none older than nine — have drawn water from the sacred spring in the hills and carried it back in beige and black vases usually reserved for funerary purposes. The vases, Anthea explains, are to remind Iphigenia that after this she has only one more important passage to make in her life, and that is out of it.

Head bowed, Iphigenia kneels over a gutter set in the marble tiles. Two of the slave girls pour the spring water over her hair, her skinny shoulders, the bluewhite concatenation of her spine.

Iphigenia thinks: This is how it feels to become another person. Iphigenia thinks: Three more hours, and I shall populate the center of a completely new tale.

One night, she watched Electra standing among vast sand dunes pressing her palms against the flank of a white Arabian horse.

Each time Electra pulled her palms away, crimson imprints remained behind.

Soon, bloody flowers covered the horse's side.

When Iphigenia awoke, the sheets between her legs were soggy with metallic seep. Her nipples ached. It felt as though she had eaten something that was poisoning her. She decided a succubus must have attacked while she was dreaming and now she was bleeding to death.

Sitting bolt upright, she cried out in horror.

A groggy Anthea dashed in, fluttery oil lamp in her hands. Iphigenia's attendant ran her hands over the frightened girl's body, searching, taking stock, calming, and, when she reached that mess between her thighs, she broke into a wheezy cackle.

You're not dying, child, she said. You're just growing up.

Next morning, Anthea mixed corn with Iphigenia's menstrual blood and spread it on the nearby fields to celebrate her newfound fertility.

Her proud father gave her a cheetah cub the size of a housecat. The fluffy fur along his backbone and atop his head stood straight up so that it was impossible to take his pipsqueak growls seriously. Iphigenia named him Zeno because she liked the sound of bees and surprise living inside the word.

Her mother, whom she often did not see for weeks on end, said nothing.

Then she said nothing again.

Iphigenia has always loved most to play by herself. She has never fully understood the need others have for others. Give her her own corner of creation, her own sanctum, and she will amuse herself happily for hours with the intricate mechanical bird her father brought back for her from across the sea, the doll made of rags, wood, wax, ivory, and terra cotta he brought back from Athens, Zeno sprawled nearby, absorbing the marble floor's coolness, dreaming cheetah-cub dreams. On good days, her mother leaves her alone. On good days, her sisters and brother, too. There are many good days. She likes to roam the cool echoey palace by herself. Without such lingering moments of privacy, how can one possibly find the time to consider the ideas arriving in one's head like a school of parrotfish? But now that is going to change. Iphigenia is vaguely apprehensive before the notion of having a new friend for life. She is excited as well. From now on she will always have someone to talk with at night when she is too tired to do anything except curl up in bed, but not tired enough to fall asleep. She will no longer have to endure the way her big bully sister Electra with the bad skin sometimes for no reason reaches over as they pass each other in the corridor and pulls her hair, hard, to make her cry, or the way her big bully brother Orestes with the smelly farts sometimes for no reason lies in wait and jumps out from behind columns to take pleasure in terrifying her and making her drop what she has been carrying. She will no longer have to endure the way her little sisters Chrysothemis and Iphianissa tell her she will be invisible to them for the next three days and then refuse to talk to her. Iphigenia will get her own beautiful house with her own beautiful courtyard and her own beautiful altar. She will never step outside again. She already knows what images her pebble mosaics will include. Her pebble mosaics will include images of Pegasus. Iphigenia adores horses and birds. She adores things that run. She adores things that fly.

Читать дальше