“What do you want to talk about?” he asked.

“Talk to me over here,” I said. “Please.”

Reluctantly he stepped out of line and toward me, one hand in his pocket, the other scratching his red ear again. I wondered if it was infected. “You need to get a handle on your kid,” he said quietly.

“I know,” I said, wallet out of my pocket. “You’re absolutely right. But listen, the thing is, he’s not even mine. He’s my girlfriend’s kid, and I won’t lie to you. He can be a real pain in the ass, okay? The other night I caught him spitting in my red wine. He hates me, okay? But listen, he’s got to see these monkeys. If you don’t let him—” I handed him two twenties. “If you don’t, I’ll never hear the end of it. Please, help me with this.”

The official shoved the money back at me. “No, no, that’s not what this is about,” he said.

“Then what is it about?” I asked.

“It’s about respect. He doesn’t have any.”

While that was true, I wasn’t going to say so to this guy.

I needed a different approach and quickly settled on pity. “This isn’t his fault,” I said. “I’m the one who lost our place in line. No need to punish him, right?”

The official didn’t say anything.

“The kid has problems, okay?” I continued. “He’s a sick kid. Check his backpack. He has to carry around his medication. He has to give himself shots, all right? I’m pretty sure that’s why he wants to see these baby monkeys. I think he relates to them on some level.”

The official’s ear was so red I thought it would burst open. He stopped scratching it and considered this new information.

“What’s wrong with him?” he asked.

As far as I was aware, diabetes was the extent of it, but I told him it was lots of things, that I couldn’t say exactly what it was because his mother didn’t like for me to talk about it, but it was bad.

The official shook his head back and forth, his mouth a rigid line. “Regardless, he needs to apologize,” he said.

“Yes, of course,” I said. “Definitely.”

We walked over to Val, who had never abandoned his place in line.

“Val, apologize to this gentleman,” I said.

Val was about to say something — something offensive, I was sure of it — so I made a face that I hoped he would understand, my eyes wide, lips pursed. He fidgeted with his backpack straps, uncertain. “Okay,” he said, and looked up at the official. “Sorry. I am. I was just excited.”

The official nodded and said, “You can’t just go around doing whatever you want to do. That’s not how life works.”

Val didn’t respond. This was a lesson that he probably needed to learn, and now, because of me, maybe he never would. He looked up at both of us with the same cool stare, waiting to see if he was going to get what he wanted, and of course he did.

“He can go in,” the zoo official said, then turned to me. “But just him. You’ll have to wait outside.”

“Why?” I asked. “We’re together.”

“Take it or leave it,” the man said. “I’m only letting in one more person. You or him. Up to you.”

Val looked up at me victoriously, apparently not doubting that he’d be the one to go inside. That’s the way it is with kids, I suppose: they take it for granted that the last cookie on the tray is for them. I told the guard thank you, though I suspected this was all his way of clinging to the little bit of authority he had left. He was being petty, but I let it slide and took my place beside Val. A few people tried to join the line after that, but the official shooed them away. He brought over an orange cone and dropped it directly behind us. Val watched that procedure closely, happy of course to be on the right side of it. If the boy had any new respect for me, he certainly didn’t show it.

“I’m glad it’s working out,” I said, and raised my hand unconvincingly for a high five. But Val didn’t want to meet my hand up high. He stuck his palm out low, and when I tried to slap it, he snatched it away at the last second.

“I’m still sensing some hostility,” I said, trying to be funny, and, in the absence of any laughter, mine or his, feeling more upset. “To be perfectly honest, I wouldn’t mind a little more appreciation, pal. I just got you into this party.”

“Thanks for that,” he said. He was such an easy kid to dislike.

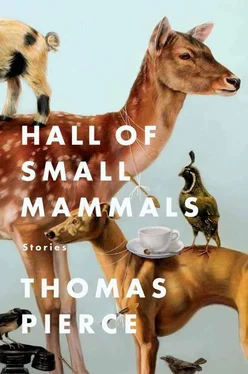

He got out his phone and double-checked that the flash was disabled. We were quiet until, finally, it was his turn to enter the Hall. Inside I could hear a movie presentation about the Pippins, the narrator’s British accent. Cool air gushed out of the dark hall in powerful and pleasant waves. It felt wonderful and inviting. I still had no love for the poor baby Pippins, but I wouldn’t have minded seeing what all the fuss was about.

The zoo official was holding open the door with his back, his hand on the horizontal bar, ready to swing it shut behind Val. Without exactly intending to, I’d come very close to the entrance. For a moment I wondered if he was actually going to let me pass as well, if maybe he had forgotten or no longer cared about this part of our agreement. But as I approached, he shot me a hard look, almost daring me to take another step, and I knew that if I pressed forward, he would stop me, or possibly even the both of us. Val shoved his backpack in my direction as though to prevent me from trying.

“Don’t lose this,” he said. I watched him go forward, hands deep in his pockets, and then pass through the door alone. He didn’t turn back to say Thank you or I’ll see you on the other side or anything else. He acted like I wasn’t even there, like he’d already forgotten me.

To prevent the newest discovery from winding up in yet another showman’s dime exhibit, we decided to send one of our own to bring it back for safekeeping. Tall, cheerful Dr. Anders was the first to volunteer for the trip, though among the naturalists in our Academy interested in vertebrate fossils, he was by all accounts the least qualified. The young doctor had recently caused a stir by mistaking an adolescent mastodon jaw as proof of an entirely new genus and species. A laughable idea. But what Anders lacked in credentials, he made up for with his unwavering enthusiasm — and (it need be mentioned) with his political connections. By luck or by connivance he had become engaged to a woman from one of the city’s wealthiest families, and that family, thanks to Anders, had made significant contributions to our esteemed Academy. Those kindnesses considered, we could find no reason why it shouldn’t be Anders we sent to procure what was rumored to be the most complete specimen yet unearthed.

On the morning of Anders’s departure we accompanied him to the station, the trains steaming and hissing all around us as we clapped him on the shoulder and wished him well. “You won’t be disappointed,” he said, confident. “Because when I return, I will come bearing gifts millions of years in the making.” Prepared remarks, no doubt. It was winter and we stomped our feet to keep out the cold. “Very well,” we told him, and watched his train crank away and disappear into a gauzy rain.

He traveled twenty hours south to a provincial town called Newton, where we had arranged for his transfer to a stagecoach. Unfortunately the promised coach did not manifest (its driver, we later learned, had fallen down drunk and been trampled by his own horses), and Anders was forced to finish the journey on the back of a mule cart that happened to be on its way to the town of Golly, his final destination. If not for this setback, perhaps history would have been quite different for Anders, for our Academy — and for science.

Читать дальше