“This is it for me,” Cecilia said. “This has to be it. It’s not healthy to dwell on this for too long.”

Bert nodded and Delia said, “For us too. Absolutely. This is goodbye. That’s what I keep telling Bert. We have to move on. Right, Bert?”

“Right,” he said. “Yes.”

The helicopter banked left, and they fell forward into their seat belts. For a moment Bert feared the pilot was trying to toss them, but then the craft evened out, and they were on their way home.

• • •

His oldest daughter was visiting from out West the day three large cardboard boxes showed up on the doorstep. They contained some of his brother’s belongings, the tapestries and photographs from his apartment, the stone Ganesha. He paraded it into the kitchen, where his wife and daughter were boiling water for tea.

“No,” Delia said. “Absolutely not. Not in this house.”

“Oh, he’s not so bad,” his daughter said, holding it under its lowest arms like a toddler. “He’d make a pretty good doorstop, I’ll bet.”

“I’m taking him to work,” Bert said to Delia. “You won’t have to ever look at him again, I promise.”

“You’ll scare off all the customers,” Delia said, pouring water into mugs. “People will lose their appetites. The business will go under.”

It had been almost a year since their helicopter ride, and in that time he’d scrapped plans for a fourth Pop-Yop franchise and sold his third location to its manager, a nice young girl who, he had to admit, deserved most of the credit for its recent success. Bert wasn’t ready for retirement, not yet, but he could feel himself losing steam. He had plenty of savings. He and Delia had even talked about traveling more, possibly on a cruise, in the Caribbean or in the Baltic or, eventually, both. He imagined himself standing on the lido deck with a cigar and seeing, in the gray distance, his brother’s ship. Wouldn’t that be something, brothers on tandem ships.

Rob was out there, somewhere. Mrs. Oliver, who’d been emailing him less and less frequently, sometimes wrote Bert notes that included only GPS coordinates. To keep track of his brother’s movements, he bought a small world map that he could fold and keep in his wallet. He recorded Rob’s route as a series of dots across the latitudinal and longitudinal lines. His brother traveled south across the Atlantic, around the Cape of Good Hope, and then east across the Indian Ocean, where he was transferred to a military plane and flown to an undisclosed location off the Australian coast. He was there for a full six months before details surfaced that he was on the move again, this time north to a research facility off the coast of Japan.

There, they dipped and froze Rob’s body in a mixture of gelatin and water and then cut the entirety of him into wafer-thin sheets. Each slice, only a millimeter thick, was scanned and digitized. Scanning one layer meant obliterating the previous one, and by the end of the process, Mrs. Oliver explained, there was nothing left of him, as he’d been ground up into a fine and invisible dust, neutralized and vacuumed into nonexistence.

God forbid Rob should ever rise from the dead: Bert wrote this to Mrs. Oliver with a glint in his eye, as a joke, but after pushing Send, he realized it was no joke at all. Some part of him really did wonder if there was something to it, to the idea of a physical resurrection, of the roaming spirit’s future need for its body.

Mrs. Oliver never addressed that particular concern, not explicitly, but she did say that she didn’t want Bert to worry. In fact, she saw no reason why Bert shouldn’t get his own copy of the slides. His brother was computerized now and, as a digital entity stored on a number of servers, he would quite possibly outlast them all.

And so she began transmitting his brother electronically as a tremendous file that contained over two thousand high-resolution images. The software that assembled them did so in real-time, and over the course of an afternoon Bert watched his brother load onto his computer, the layers stacking into a familiar shape — toes, feet, ankles, legs, knees, all of it adding up to…

… to what, exactly? Entire parts, he realized, were missing: an arm, a section of shoulder, his mouth, an eye. Though Bert could flip through his brother’s body like the pages of a book, could click down through the pale skin, could rotate each bone and navigate the world of his organs, Rob remained an incomplete specimen, a redacted document. When he let Mrs. Oliver know this, she was embarrassed to admit that she hadn’t yet secured the rights to certain slices, the scans of which were currently on lockdown for reasons she couldn’t disclose.

To Bert, this latest — and possibly final — hiccup was so absurd he considered breaking off communication with Mrs. Oliver altogether. He printed out his brother’s incomplete naked body on his office printer and called up Mrs. Oliver. “You’ve done all you can,” he told her. “And I’m grateful for that.”

“We’ll get the clearance,” she said. “Eventually. I promise you that.”

The stone Ganesha was on the shelf above Bert’s desk, and he stood up from his roller chair so that he was eye-level with it. “And I don’t doubt you,” he said to Mrs. Oliver, cradling the hot phone between his ear and shoulder so that he could fold up the printout of his brother and stick it under the statue. It was off-balance now and seemed to lean forward. Bert stepped back and bounced the floor to make sure the statue wouldn’t come tumbling off the shelf. It seemed sturdy enough.

Mrs. Oliver was still on the line, reiterating how committed she was to securing the rest of the files and completing the process. She would be there for him, she said, almost pleasantly. She would continue to work on his behalf with the powers-that-be. “More as I have it,” she said, and hung up.

The zoo, finally, was going to let the public see its baby Pippin Monkeys.

“I bet we won’t be able to get very close,” Val said. Like always, he had on his blue backpack, the one that contained what I understood to be his novel-in-progress, plus his supply of granola bars, arrowroot cookies, popcorn, and insulin injections. The water bottle clipped to the side of the backpack was metal and shiny in the cloudless afternoon heat. Val was my girlfriend’s twelve-year-old son, and I wanted him to like me.

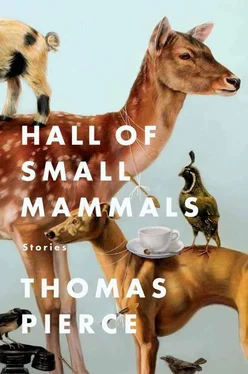

We were at the back of a very long line that began near the Panda Plaza and wound all the way around the Elephant House. Nobody was very interested in the elephants or the pandas at the moment. Everyone was at the zoo for the baby Pippins. If just one of the three Pippin Monkeys survived to maturity, it would apparently be a major feat for the zoo, since no other institution had been able to keep its Pippins alive for very long in captivity. The creatures came from somewhere in South America. They were endangered and probably would go extinct soon. But before they did, Val wanted to see one up close: the gray fuzzy hair, the pink face, the giant empty black eyes. Val wanted to take a picture to show his friends.

“I can turn off the flash,” he said, messing with his camera phone. We had just passed a sign that banned all photography once we were inside the Hall of Small Mammals, where the Pippins were on display for one weekend only. “No one will notice,” he said.

“Just be covert about it,” I said, though I didn’t really approve. Generally I don’t condone rule-breaking of any kind. I’ve always been this way. At the airport, when there’s a line roped off for the check-in counter, I will walk the entire maze, back and forth, even if I’m the only one there to see me do it. If my car barely protrudes into a nonparking zone, I will drive for miles in search of another spot.

Читать дальше