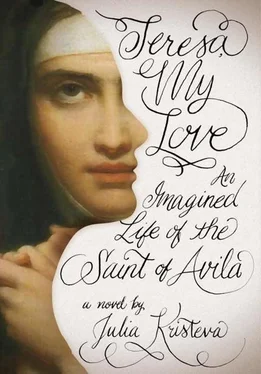

But your genius was not only to make the most of that ecclesial strategy to restore your health. You took possession of the writerly space thus constituted, and your discourse was forged in perfect accord with that scriptorial dynamic whose quintessence you had extracted and into which you drew your scholarly directors of conscience. You confected a mobile idiom that took shape on the page at the same time as in your body.

Hence you were less intent upon what might make a book, and more concerned with the actual transformations this writing worked in your physiology and your relationships with other people: “I shall give you a living book,” as the Lord told you. That “living book” was yourself and your monastic foundations, in the wash of a text made incarnate in actions. Between the loss of your selfhood in a drive whose very frustration was gratifying, and the thought that absented itself from that regression at the moment of the event, only to join it again a moment later: such was the oscillation of your life in writing, a thinking that immersed itself in desire and nevertheless gained mastery over it.

You deployed the whole gamut of psychic capabilities. And you named the sufferings and the pleasures embedded in the palette of sensations — visual, aural, olfactory, tactile, motor — without omitting to bracket them with the intellect, that is, with the ideals of your family and religious upbringing. On the wings of exaltation or in the abyss of despond, you were illusion itself, and yet without illusions. Outside yourself, ek-static, you caught and recentered yourself once more by talking about it, sure that whatever you might have to report was better than the unspeakable. For it has not merely to do with Nothingness, and has certainly nothing to do with death, but rather concerns a “to die,” in the infinitive. Your infinitive dying endures in the range of perceptions that separate the Self from its Self in order to pour it into the Other, to make it become Other. It mutates into rebirth in this Other, but never once and for all, because this infinitive dying is spoken and written indefinitely, in the flux of time and waters. And so your written word paradoxically imbues Truth itself: a floating Truth, programmed but indefinite, infinite.

Such an ambition was folly in the sixteenth century, when many were burnt at the stake for far less. You dodged the Inquisition by persuading the Church that in order to comply, both with the reformed branch’s call for cleansing and with the yearning for miracles proper to an economically and sexually deprived congregation — in order to trim reason to fit faith, in other words — what this era of Lutheran heresy required was an ascetic, ideally female, who happened also to be a supernatural wonder.

You alone could satisfy this double requirement. You — that is to say, the talking and writing that refurbished your body and in which you yourself became embodied. Skillful, astute, indefatigable, energetic, you lobbied the entire Church hierarchy: alumbrados , Franciscans, Dominicans, Jesuits, Carmelites, naturally, the Vatican, obviously — nobody escaped, including the Spanish monarchy and its satellite nobles.

Transcending historical eras to beguile me today, your writing reaches us in the manner of that liquid matter you adored, in watery spurts and streams. The Spanish word agua flows freely from your pen. Water is not so much a metaphor as a sign for the metamorphoses of your supposed identity in the very act of writing: you cascade from one state into another, from convulsion to jubilation, from sensations to their comprehension, from Gospel stories and characters to the virtuosity of the next overwhelming insight, from disclaiming the understanding to claiming knowledge, from looking to listening, from savor to skin and thence to so delicate an intellectuality that it barely brushes the mind before eclipsing it. Movement, flux, dipping and diving, all the facets of a butterfly forever returning to its chrysalis are folded into the dwelling places of the garden: fragments of everything, flashes of nothing.

As a child you evoked “the nothingness of all things [ todo nada ],” 4now you say yes to this all which is nothing, this nothing which is all. Yes to your visionary opus, which is not an obra , an object, thing, or product, but a continual metamorphosis. Your writing, which prefigures and accompanies your commitment as a founder, is really an infiltration of words into things and things into words without collapsing the difference between them. By writing, you hold psychosis in suspense. Your love madness is nuanced, filtered through a mesh of perspicacity in the very midst of swoons and comas, with a clarity that’s infectious.

For all their subtleties, your interior and exterior experiences do not by any means make you into a precursor of psychoanalysis. Still, the precision with which you record your visions of the Beloved, that blend of sexual sensation and fragmentary thought, all dissected by the scalpel of your watchful intelligence and wit, have much to teach the stalkers of the unconscious. It could even instruct Lacanians, who already know a thing or two about those excesses of yours that defeat, I fear, most other colleagues — including Jérôme Tristan, if he will excuse me for saying so.

Indeed it was Jacques Lacan, himself born into the Roman and Apostolic Church, who first extolled the jouissance he thought he detected in you and defined it as other . For it twines around the paternal phallic axis a novel way of being aroused: sensory, forever unsatisfied, and for that very reason outside time, on a cosmic scale. You not only experienced this female jouissance but also, and more importantly, recorded it. Otherwise how should we have known? Your great exploit was not so much to feel rapture as to tell it; to write it. Lacan saw you less as a “case” than as the intrepid explorer of that desired, desiring otherness that used to be called the divine and is at work, according to psychoanalysts, in all human beings, believers and unbelievers alike, as soon as they speak or refrain from speaking.

Nevertheless, unlike some academic critics (such as the great Jean Baruzi) for whom the mystics were forerunners, giants- manqué of the metaphysics to come, 5I do not regard you as agiant- manqué of future psychoanalysis. In your “I live without living in myself,” the “psychic domains”—those constitutive spaces of the soul you so elegantly laid out into seven dwelling places of your “metapsychology”—were in reality more often crushed on top of one other. 6But though this collapsus plunged you into great mental confusion, catatonia, or coma, you proved capable of making your way through and lifting it up as a thought-body, in an unprecedented, exceptional body-thought. You rose there to a grandiose sublimation that most of us have only known in fragments, faltering words, hazy approximations. Few have ever achieved so complete a convergence of regression and reason.

You knew that sexuality is the carrier wave of love, especially the love of God, even if you only said so indirectly, through fiction, fable, and metaphor. You heard the Other whisper: “Seek yourself in Me.” This certainty, this truth was so enthralling that you no longer dared to think outside of Him, in your own name, alone: ego Teresa . Except for a handful of pages (that you cut from the final draft of The Way of Perfection ), your thinking was always to unfold with Him and from Him, and that is why it is a love thinking, rather than reasoning pure and simple. You are not quite a Cartesian, God forbid, but your lucidity prefigures the love in transference and countertransference. And if the narrative of the moods of your soul hardly constitutes a novelistic plot, it is nonetheless a novel about the consciousness/unconsciousness of love.

Читать дальше