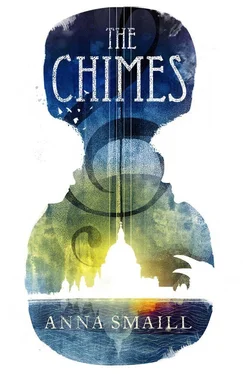

‘It’s not your mother’s memory,’ I say. ‘And it’s not yours either. It’s Sonja’s.’

Lucien stares blank. ‘But it’s my mother’s ring,’ he says. ‘She never took it off.’

I think through the pictures of the memory lento. I want to tell him exact. ‘I was walking down a white corridor. It was, I think, inside the Citadel. Then I was with your mother in a room at her bedside.’ I pause. I don’t know how to say it. ‘Your mother’s hair…’ I start.

Lucien pushes himself to standing. He does it presto like if he moves fast enough, he can push away from what is coming. But when he speaks, his voice is calm.

‘Her hair was combed out and twisted, and it was threaded with glass beads,’ he says. ‘Her hair was like a stave, and the beads formed a melody that sounded along it.’

I nod.

‘I always hated that ritual,’ he says, and his calm scares me. ‘How can you take a person’s life and make a single melody from it? Everything they’ve ever said or done. All they were to other people. As if a tune can sum that up.’ He spits on the ground. ‘The magister musicae composes all of them, you know. And then he sings them into death. People he probably barely even recognises. People he wouldn’t have deigned to speak with. Whose names he never even knew.

‘I hate it. A neat glass tune for a life and how grateful we are all meant to be. But it’s just lies.’

He stops. His shoulders are shaking. His voice is cold, as if I am a student and he has been given the task of stripping away my illusions. ‘ Grief is not a note to be sustained after death ,’ he says. ‘The threnody becomes the melody simple of the funeral mass. I must have been in London when they played my mother’s, then. I didn’t even get to hear it.’

I sit next to him. He looks up like he is surprised. His eyes are dry and staring. I take his hand.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say. Then, ‘Don’t.’

‘Was it easier?’ he asks. ‘Knowing you would forget them?’

I don’t answer that. Just sit with him while he cries.

The next morning is cold and sharp. I wake on hard ground in the corner. From where I lie there’s a clear view of the wooden cross at the end of the room. The wooden man on it stretched somewhere between life and death. The look on his face like the rigor of chimesickness. Lucien’s arm lies over my shoulder and my chest. I lie as still as I can so as not to disturb him.

It’s a while before Matins. The window at the end with the chips of coloured glass still in it shows no light shining through. I would gladly lie still with Lucien’s arm over me until next Allbreaking, but I can tell by his breath that he is already awake. He sits, stretches.

I watch him. He stands and shakes the stiffness out of his legs, and then he walks from one side of the crosshouse to the other, turns and returns to stand just behind me, out of the line of my sight.

‘I dreamt that I could see,’ he says. ‘I was due to go on stage to play the Carillon for the induction ceremony. I was all ready and I sat down. And it was as if my fingers were sick. The muscles acted against me. They didn’t believe anymore what I was doing. I could hear the music, but it meant nothing. There was no time in it, and no time for it. No future and no past… I can’t explain it. I knew it wasn’t part of any world outside of the concert chamber. There were red velvet drapes drawn, beautiful heavy velvet. They were there to keep out light. And they were keeping out time, and death also.

‘I was so desperate to leave the stage. I couldn’t even remember what I was meant to play. But I didn’t have anywhere else I could go, and I didn’t know what to do, so I sat down and played the piece through. I could see the audience’s faces, and they were horrible. There was nothing inside them. No pleasure or disappointment or anything. And it was like I was crumbling on stage, cracks forming in my fingers and through my head, and I knew I would break at any moment.

‘I tried to tell them. It seemed they should understand — they could see it in front of them. But I couldn’t stop playing. My fingers wouldn’t let me. The playing was ugly and clumsy, but I couldn’t stop. I wanted to shout out that they needed to let me stop, but I couldn’t. And they just kept staring, waiting for me to finish.

‘I must have finished at last, because at some point the hall, the magisters, the students, all of them rose up in one single movement to applaud. I saw their dead eyes and their hands clapping and it was just the same empty sound and it meant nothing. So there I was dying, and they clapped. And I realised that not a single person among them, including my father, cared who I was, cared if I lived or died.’ He takes a breath. ‘That is the life of the Order. I’ve been deaf to it as well as blind. We go on as before,’ he says. ‘There’s nothing else we can do.’

‘We need to get a message to Sonja,’ I say.

Lucien is silent for a while.

‘There used to be a viol maker across the east side of the market place,’ he says. ‘He was the best in the city. He and his prentiss used to enter the Citadel every eightnoch to sell bowhair and strings to the Orkestrum and do repairs. I am sure he is still alive.’

‘We gave the last of our tokens to Callum,’ I say. ‘We’ve nothing to trade for a favour.’

‘Then you will have to rely on your good looks and native charm,’ says Lucien.

After Matins I leave Lucien, whose eyes will betray him, and I head east toward the pull of the Lady. The streets are filled with people. I watch the ones carrying shopping baskets and follow their path until I reach an open market in a large cobbled square.

Buyers walk calmly, and talk is muted. All the flinty chaffer and dash of bargaining is missing. No roughcloth on the cloth vendor’s cart, just linen in pale creams and whites. Gold and silver broderie thread on large wooden reels. The traders’ eyes slide over me, too full of their own dignity for spiel or swagger.

Off the market street and down the wide avenue to its east. All of the shops are large and well kept, and they’re hung with the guildsigns of instruments. Highboy. Trompet. Clarionet. Flute. The thick, clear para windows are polished bright and behind them strange and inventive displays. I stop at a casement backed in rich blue velvet. Dozens of trompets hang inside, tied by invisible thread and spinning tacet, sending out sparks and rays of golden light across the street.

Basson. Klavier. Slip horn. Cello. I stop in front of a red door. Viol.

A low chime from the doorbell and I’m inside. Candles bright against the dark of the windows and the smell of rosin rich and piney in the air. Scent of glue and varnish and the warmth of wood. Viols hang on the walls, their scrolls resting between specially turned pegs. The bows lie in a field of green velvet inside a low case. They are wonderfully beautiful, inlaid with ivory and coloured stones. I can see through to the adjoining workshop. A bench covered in leather. Two heads, one grey and one blond, inclined over a curved piece of wood, the belly of a viol.

The viol maker takes his time in looking up. When he sees me, he hands the woodplane to his prentiss and says something under his breath.

Then he walks into the showroom slowly, rubbing his hands on a cloth.

‘What can I do for you, young man? A new string, perhaps? A block of redpine rosin? Or does something else catch your eye?’ There is humour in his words, but he moves with caution, a wary eye on the precious goods around me.

The prentiss watches from the workshop. He has taken in my ragged clothes and grimy face and is waiting to be entertained. I will not disappoint.

Читать дальше

![Чарльз Диккенс - Колокола [The Chimes]](/books/395589/charlz-dikkens-kolokola-the-chimes-thumb.webp)