‡ Situationist International Anthology , trans. Ken Knabb (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2007).

§ Which doubled as foreplay. — CD

On April 16, 2010, Taer was drinking red wine alone in Molly Metropolis’s two-story office, trying to focus on a proposed addition to the Purple Line circa 1950, meant to more fully accommodate the expanding western suburbs. (The proposal wasn’t considered cost-efficient and the Transit Committee rejected it.) Taer couldn’t concentrate; she found herself standing in front of Molly’s full-length mirror, experimenting with drugstore eye shadow. With a glass of red wine in her left hand and a makeup brush in her right, she listened to Cause Célèbrety and watched a “smoky-eye tutorial” on YouTube. She then wrote a Tumblr post, complete with selfies, describing her lack of proficiency with eyeliner and comparing the helpfulness of a variety of tutorials.

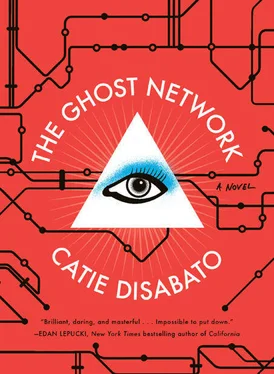

Half an hour later, her eyes were very smoky and she was significantly more drunk. As she later described to Berliner and Nix, Taer stumbled back to Molly’s desk and, humming along to “Famous Case,” Taer opened the MollyMaps program. She clicked around aimlessly for a while, not researching so much as stumbling through the program, drunkenly ambling from corner to corner of the crowded virtual map.* She turned on the voice recorder on her iPhone and rambled for a bit about wanting to meet Molly, how happy she was to be with Nix, who her Carey Mulligan — inspired character Jenny had been, what she had wanted in life, and what, exactly, Molly meant when she was going on about the “Pyramid Eye.”

“There is a website that says pop stars are Illuminati puppets,” Taer said, “which is of course ridiculous until you start thinking about how I’m sitting alone in a secret headquarters basement place, which is so weird, and maybe she was just in the Illuminati and all the rest is bullshit to trap me and trap Jenny in a triangle forever, just walking around in the same terrible triangle her whole life. How sad is that? We’re all trapped all the time aren’t we, except Molly who got out of here. But I bet even Molly had a triangle! I wish I could—”

Taer stopped talking and for nearly ten minutes, her phone’s voice recorder only picked up some faint clicks from the mouse on her computer.

Then she spoke again, one final rejoinder: “Oh holy fuck.”

Maps have never been accurate. The best they can achieve is a high navigability. In the Exploratory Age, during the first big brouhaha over mapmaking, early cartographers with imperfect knowledge of foreign geographies used flawed equipment to draw maps with as many errors as accuracies. Cultural biases, such as those displayed in the Edge of the World maps, created absolutely abysmal conditions for rigorous accuracy. While Christopher Columbus attempted to circumnavigate the globe in search of gold and spice, most of the “rude class” still believed sea monsters filled the boundary waters between the safe continents and the black void of the unknown.

Modern day maps are still full of inaccuracies. They do a terrible job documenting borders, and are a hopeless match for the rural dirt roads that run between corn and sod farms in Ohio. Lazy mapmakers who use blueprints provided by city planners, rather than conducting their own cartographic surveys, accidentally include “paper streets” on their maps: streets that city planners or subdivision developers include on their blueprints but, for a variety of reasons, never get built.

Beyond even these unintentional discrepancies, some maps have inaccuracies deliberately added, those maps offered up as consumer products like London’s ubiquitous street guide, A — Zed . They are called “trap streets,” and they are purposefully fictitious; map publishing companies add them to protect their copyright. If another company sells a map that includes their false trap street, the first company knows their copyright has been violated and can sue. Trap streets are used as a weapon in corporate warfare, but in certain circumstances, trap streets can be used to fight a different kind of battle. Molly Metropolis certainly understood the importance of trap streets, and as she constructed her map of real train lines and paper ones, she included traps of her own.

Molly’s trap street was a train line that didn’t exist on any of the historic maps. By the time Taer was looking through The Ghost Network, it had been reduced to one errant, and tiny, dot. On the digital version of The Ghost Network, each train line was marked in a different color, and every dot that represented a station on the line was the same color as the line. Clicking drunkenly through The Ghost Network, in her digital dérive , Taer got lucky and stumbled upon a dot not connected to any train line.

At first, she thought she’d accidentally deleted the connection between the dot and the next nearby station. Then Taer noticed that the color of the dot, a pale and almost metallic pink, didn’t match any other dots and lines nearby, nor any other dot she could see. The dot had been placed on the map at the intersection of Armitage and Racine, at the location of the very building Taer was then sitting inside. Taer scoured the map for any other trace of the distinctive pink. She didn’t see it, but she wasn’t discouraged.

She flipped to a particularly oblique passage in Molly’s notebook:

I found that the [New Situationists] left enough marks to follow, toeing the Party Line but didn’t leave their Pyramid Eye to make an easy path. I can’t tell if they were performing or acting, or if there is a difference between performing or acting, but I will find out and if I find anything, I’ll leave my Third Eye behind to make a map on top of a map on top of a map like I’ve always done. To be fair to them (Debord and my sweet Nick, who answers to a higher power [currently incarcerated]), I won’t leave an A — Zed sort of a guide, will I? Everyone will have to find something in the lattice. Who am I to deny my dearest ones the fun of their own mystery to solve?

Taer copied the passage into her own journal, circled the word “marks” in the first line, and next to it, she wrote: “pink one at A&R.” Taer also wrote several question marks next to the phrase “Party Line,” and wrote: “Why capitalize this?” Next to the words “Third Eye,” Taer wrote: “Third Eye equals a Pyramid Eye equals a triangle, like Jenny’s triangle. We have to find Molly’s triangle.” She thought the errant pink dot was one apex of a secret triangle, not present on any of the historical maps, which Molly had embedded into The Ghost Network.

For the next several hours, Taer searched the map for the second point in Molly’s triangle, and finally found another pink dot outside of Chicago proper, at the Chicago Executive Airport in Wheeling, Illinois.

The wine caught up with Taer then. She took off her bra and fell asleep on Molly’s couch. She slept until nine the next morning when Berliner nudged her awake and playfully flung her bra at her head. Rather than share her discovery with Berliner immediately, Taer decided to investigate the pink dots herself. Berliner and Nix still don’t understand why.

“She’s motivated by emotions rather than thought,” Nix said.

“She was ,” Berliner corrected, and Nix flinched.

“You don’t think she wanted to find something without you?” I asked Nix.

“Maybe. I don’t know. It’s frustrating to try to guess about it now. I thought maybe she had written something to explain why she would go searching without us, after everything, but there was nothing in her journals.”

Читать дальше