The colonel’s mouth moved less, but I thought he said either Yes or, more dramatically, Sure , as if he knew that he’d run into his destiny as a man in the dark walks into a wall.

The captain stood where he was, for the time it takes a frightened heart to beat, say, half a dozen times. I thought him brave to have paused there so long. He dove, as if into water, and landed on his belly and balls. His legs were moving to scrabble at the ground they had stood upon, and they finally took purchase, and he lurched, flailing his arms, for the roped-in paddock they had fashioned on a sparse field where the horses grazed. He rolled under the rope and into their legs. They danced about, but were too used up to more than dart and paw, then steady down and drop their heads. I followed the captain’s progress an instant, and then I swung back to the colonel, who surely could have escaped. I’d calculated he wouldn’t, and I was right. He had stood to await me. He was a very brave man. I took him with a head shot, assuring that he would not feel his end, and I was gone from there like a ghost. They thought of me, I think, as ghostly. They thought me, maybe some of them, a ghost. Walking in Manhattan, inspecting the people of the nighttime streets while walking hard, a nearly military march, to tire myself, I laughed and didn’t know why. I wish now that I knew. How I wish I could be gone like that, the ghost disappeared from the killing ground. How I wish I could be gone.

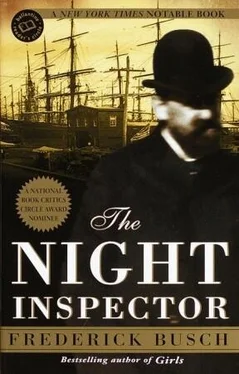

At Washington Street, where the Hudson is a harbor, and where funnels squat filthily on ships among the high wooden masts, carriages rumble and groan with God knows what inside them. Two vehicles resembling the lower Broadway horse cars, but with no roofs, rolled up toward Laight Street with a dozen or more Negro immigrants on board: The Freedman’s Bureau had carried them from South Carolina or Georgia to what might have been considered safety, and even, they might have thought, opportunity, in Manhattan. I wondered if they would live in Africa, the Five Points, or the Tenderloin. Some of them grinned, perhaps in embarrassment. They wore dark seamen’s clothing and fishermen’s caps. Most of them seemed stilled by the weight of their fright. It is a hard city, and as full of cul-de-sacs as large opportunity. They had used to be a kind of currency. Now they sought the common coin in competition with the rest of us. With some of us. Perhaps, of course, as they jolted and wobbled past, they had smiled because they saw a clownish mask. I waved at the second wagon, and a small black child, with no expression, waved in return.

Two ships, arrived overnight or at dawn, were visible at the mouth of the Narrows, lying- to in quarantine before luggage was brought to the public store for appraisal and the cargo was evaluated at the sample offices. M had a hand in all that, he had told me with self-importance and denigration at once; he was complexity, this fellow who made so much and so little of himself. As our waiter had begun to stack the dishes and cutlery, my brand-new friend held dishes, glassware, and an empty bottle from wine in one broad hand. He watched me as I noted the muscularity of his hand and fingers, and I understood how proud he was to have been a powerful deckhand and how powerful he thought himself now. His pride would be useful to know, I thought.

The wind shifted, the masts of the smaller vessels rocked, and gulls, as if tilted by strings, adjusted their angle of descent and the pitch at which they skimmed the murky, broad water. The sun took on aqueous tones; water was everywhere in the air, and the small rowing boats of chandlers and lightermen grew hazed and hard to follow. Even his name, I thought, brought on a drizzle. He gave me a case of what my mother used to call the collywobbles — the usual, at once, seemed untoward, and you thought the village dogs were wolves, and were hungry, and were waiting for you.

I walked above the docks, but the collywobbles came along. I thought of my room, or Jessie’s room at Mrs. Hess’s house, or the several snuggeries at Cheerie’s with their oak and frosted glass partitions, or the carriage cars uptown from here. Once, I was at home in the open. I had even occasionally slept away from lodgings and in the woods around New Haven while at school, though speculators were building houses there, and timber merchants were clearing whole half-acres a day. I had been at home, that is, in the world. Now I lived within. The silences, the gasps, the shrill queries of puzzled children — my neighbors in the Old Brewery had little ones who peeped about maschera —that were hushed by hard hands; I found these preferable now to the vulnerability in open spaces.

The more I stalked them, of course, the more they’d stalked me. It hadn’t occurred to me, probably until after the eighth or ninth, that they had given me a vulgar name and had come to think of me as a person instead of a series of events. Nor did I soon enough suspect that those men, woodsmen since birth, had started, in an uncoordinated but persistent way, to hunt for me. Naturally, once I had sensed it, I took to shadows, to edges, to the safe-seeming side of broad trees. I eschewed a horizon line. I slept restlessly, and I listened hard, sniffed deeply into a wind. My escort, I knew, would fret for their own safety and would not, in all likelihood, kill me out of fear or some holy distaste while I slept. But I had no other assurances, and I stood long watch on my life. For the duration of my war, I peered instead of regarded; my eyes were squinted, not open; and I slept, ate, stooled, and bathed with a weapon ready to hand.

I had asked him, “Do you see us all like your man Ishmael? In a perpetual November gloom? Peering out at the world from nooks and corners and … inner places?”

He sipped a Dutch gin and grimaced as he leaned back. I caught his arm, for we sat now in the saloon bar on benches across a narrow table.

“Shipmate,” he said, “a provident lunge. I thank you. Now. November? Modern man, you suggest, a creature of perpetual gloom. Well.” He sipped. “I used to deal, you see, in concrete realities, not assurances or declamations of the more general sort.” He stroked the spade-cut bottom of his beard. “But.” He held a finger in the air. “I did, for certain, stride along the back of the particular toward certain broad conclusions. What did you think — that is, did you find a moment for those poems of mine?”

“How I wish you were publishing your tales.”

He nodded. “Yes. I cannot do that, though. I am by circumstance as well as volition in a kind of retreat from such efforts. You behold the nutmeg grater grated thin. But the poems …”

He waited.

I lied.

I looked out at him, and I lied.

But is there not something — especially in this engine of a city, this rattling, black heart that pumps the capital and laborers and stockyard animals out and about and in and under, through darkness, filth, and the forge-bright fire — is there not a sense of the new creatures of this time and place as peerers from secret places? Do we not live, somehow, within? Cleave to privacies, spy from transoms, and listen to the sounds through one another’s wall?

Once I hunted. Now I lurk.

And he threatens now to write a poem about a man called Billy. He drinks too much. He writes too many poems.

I rambled in them all, in Squeeze Gut Alley and the Yankee Kitchen and Coenties Slip. Walnut Street was seven blocks of nastiness at night, where in the rain or mist the great mounds of coal and the mountainous granite dumps shone as if lighted from within. Vast, twisted shapes sat like immense dying animals as they rusted in the yard of the Allaire Iron Works, and still, not so far from the Hook that you might see a flesh-peddler discipline his girl — as I once saw — by slapping her with a flail of wet, rolled cloth; she would feel the pain and be frightened to obedience, but he would leave her without scars. It was business, I remember thinking. It was a conservation of inventory. The new world was business, with a frontier broader than the overall combined dimension of our every western state. It was how the national greatness, or its subtle, dark, most woeful appetites, would be expressed. As in the case of my friend M, the deputy inspector of Customs. He was a resource, and that I knew. As I surveyed the city by night and by the wet, gray dawn, so I surveyed the man who was capital to me.

Читать дальше