Into the tree, then, and up, then screened and with my back against the trunk if possible, I worked with telescope for surveillance and rifle scope for aiming. It then was a matter of resistance: wind against bullet; will to be still and invisible against the tickle of spider, ant, or fly; lungs against the seized breath; finger to trigger; cheek to stock; and, always, despair against an imitation of God Almighty in a tree to smite a boy perhaps not wearing shoes or a man who had removed his officer’s insignia to hide his rank (the sign of value in a corpse) from someone like me. I always shook and wavered, and I always steadied up. I was, finally, a hunter, and I killed them.

At Yale College, where I was to study theology ancient and modern, I read in the novels of Maria Edgeworth and the poetry of Keats. I ate sweets, in other words, and grew chubby of mind. When my uncle Sidney Cowper asked me to name the sage of our time, I told him Washington Irving. He threatened to remove his financial support, and my mother, who had given up life for a career in widowhood, naturally wept. I amended my deposition: William Ellery Channing, I testified. “Though,” I added, for a taste of danger and as a sop to what I thought of as courage, “I do admire Mr. Charles Brockden Brown.” Uncle had clearly read neither. He cleared his throat and urged the conversation toward finances and, in particular, the desperation of the chronically unemployed, among whose number he clearly foresaw me.

Although, I must say, Uncle Sidney Cowper did not dislike me. Indeed, he was as fond of me as any man I knew was fond of any man. He was a great, bulky fellow, as tall as my father and far more meaty. He was handsome in his way, my mother said, and he took his responsibilities — as surrogate for his brother, my father, dead of fever when I was but seven and my mother little more than a girl — with a responsibility I must call overzealous. He always braced me with his large, heavy hands: “Chin back, Billy. Head erect and unmoving. Don’t waver , son! Keep your belly in”—he’d have done well to follow his own advice—“and puff out your chest like a soldier. That’s a man.” Throughout such advice, his hands worked my body as if it were clay, poking at the point of my chin and cupping the back of my head, patting my belly just above the balls and pulling at my tiny tits as if I were to be shaped for once and for all by him. I did not like his hands on me, and when I saw them on my mother — not her belly nor her breast, but over her shoulders and neck of a sufficiency — I decided that my regret over the loss of my father was redoubled: once for his death and my loneliness, and once because greedy Uncle Sidney was going to wear away the flesh of those my father had left behind.

At Yale College, I learned enough to learn enough, and I was therefore situated in Cheerie’s Chop House on an evening in 1867 when I needed to be. It was undistinguished by its food or drink, but for me it was a kind of home. Cheerie had been a drover with us at Malvern Hill, and he had vowed to live as far from horses as he could, if he might live. He did, and so he lived on Eleventh Street and ran his chop house on Twenty-third, and he swore that he rarely roasted a horse to serve as venison to his patrons. He owned, I’d have thought, fifteen hairs, which he pasted with pomade to the top of his oval, pale head. He seated me without my asking it at a recessed table where the shadows fell. He left it to me to light the candle or not, depending upon whether I chose to read as I drank my wine, or eat in the gray-blue light that curtained me, permitting me to remove the mask in something like seclusion and wear only the dark silk veil.

M dined that night at eight. He had stopped on his way to the Customs in the morning, asking Cheerie to hold a small table for his supper. Cheerie was a good comrade. We had nearly died together in a canonade that killed a half a dozen horses and covered us in their blood and ropes of blue intestine. We gave each other courtesies. When he smiled his great white teeth, I thought of horses shrieking and exploding. Christ Himself may know what Cheerie thought of when he looked at me.

I had noticed M on Broadway as I walked the town at dawn and as he was going to his job. I knew his visage from a Boston paper. Then I had observed him; I had, during the War, been excellent at seeing how a man moved through his terrain. And, noting the place at which he worked, I had as well seen an acquaintanceship with him as something to possess. I stood. I was wearing the mask, not yet the veil. I walked slowly across the sawdust of the wooden floor among the peculiar rectangular tables that Cheerie had bought when a ladies’ dresses manufactory had failed in one of the recent economic convulsions. I moved into the man’s soft, myopic vision. Even his beard looked soft. He reminded me, though his hair was darker, of dead Sergeant Grafton.

“Sir,” I said. He look up and squinted, as though I were dozens of yards away. I could study the pores of his strangely youthful skin. He did not, through his complexion, manifest his service on the sea or on the shore.

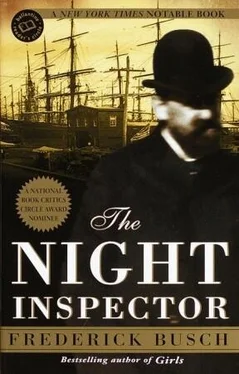

I said, “Sir. I beg your pardon for this intrusion. I have read your work. I have read The Ambiguities and its analysis of your profession. I have read The Whale . I think it a blinding brilliance, the epitaph of our economy.”

His eyes dropped, then returned, squinting at the mask. “No,” he said, “but with thanks. I wrote expressly not for money when I spake my piece about the whale. And I was given justice: I made no money. Though, to be sure, it remains the king of most kings.” He could not keep his eyes from my mask, even as he knew I observed their fascinated study.

“Begging to differ,” I said.

He gestured at the vacant chair, and I nodded, then sat.

“You were differing,” he said.

“The whale does triumph over your captain’s will, and that of the industry on whose behalf he fished. It’s a type of the national economy that founders when nature, in the guise of a whale, decides to strike.”

“But it was Ahab, a man, mighty or not, who struck through the …”

“Mask,” I finished for him.

“My regrets. I could not say my thought without including your misfortune. My most profound regrets.” He swallowed half his glass of claret wine, then waved his arm for a waiter, saying, “Please to dine with me, Mr.—”

“Bartholomew,” I said. “William Bartholomew. I am honored.”

“And I am flummoxed,” he said, leaning back his large head, affecting to laugh, though uttering no sound, as his nose pointed toward the ceiling and his mouth gaped into the air.

My dinner was brought, and wine was poured. He sat silently when I replaced the mask with my veil, although he as well as I heard someone at a nearby table gasp. I watched him close his eyes as the mask came up and the veil dropped over my head. I was charmed by his willingness to shy away from what I thought he’d spent his life in trying to peruse. And then we spoke, as we ate pork and cabbage, of what he called his career. He reserved his anger not so much for those writers who had pronounced him mad, or simply gone dry on him, but for the Brothers Harper, who had printed his books. I noted my recollection of Putnam’s, whose printing of his Piazza Tales I had read at with little interest. He asked me about something called His Fifty Years of Exile of which I had never heard, and I lied that I had read it.

“But it’s the publishers you blame, sir.”

He said, “They are mere manufacturers of black shapes on white pages. They post me invoices still, for books of theirs, often by me! that I’ve been sent. But not a human word about the writing of language to be read by students of human ways.”

Читать дальше