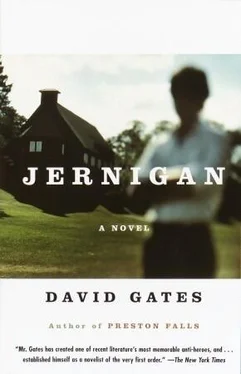

David Gates - Jernigan

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Gates - Jernigan» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Jernigan

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jernigan: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Jernigan»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Jernigan — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Jernigan», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Some,” he said.

“Stuff for Clarissa?”

“Dad, I don’t get why you’re asking me this stuff. You mean if we already bought Christmas presents we shouldn’t let them go to waste or something? I can’t see what you’re saying.”

“I’m just trying to think,” I said.

“Look, we might as well just stay, you know? You and Mrs. Peretsky are doing okay again, and I get along with her really good and I can handle Clarissa okay. I mean maybe she’ll OD or something.”

That got me to look up.

“I’m kidding,” he said. “Dad? It was just a joke. You know. Joke?”

“Well,” I said, “I guess we better get this done.” I got to my feet, leaning again on the ax handle. “Here. What’s the problem with this one right here?”

He looked. “Come on”

“Seriously,” I said. “Take it down and just use like the top six feet of it. It’s got a nice shape up there.”

“You’re going to cut the whole — look, sure, I don’t care.”

“Good,” I said. “Decided. Now let’s clear away some of the little brush over that side, okay? And then we’ll be in business.”

He started just whanging away with the scythe.

“Hold it, hold it,” I said. “Let me show you.” I took the scythe from his hands. “You want to keep the blade level, okay? And …” I demonstrated. “Like so. Short strokes. It shouldn’t take a lot of effort.” I showed him again.

“Okay, okay,” he said. “Let me try.” He tried. “Right,” he said. “Works better.”

“Thought it might,” I said, with fatherly understatement. So this was the moment I thought we’d never have together. However I might eventually come to remember it, it wasn’t much right now.

When he finished, I went in and hacked away the tree’s bottommost limbs to give a clear shot at the trunk. “What do you say?” I said. “You want to do the dirty deed?”

“Yeah, I guess.” I handed him the ax and he stood up to the tree as if at home plate.

“Okay, now—”

“I know,” he said. “Cut it like you’re cutting a thing out of it, right?”

“And don’t chop off your foot in the process,” I said.

Danny managed to get the tree down, then I took over the rest of it. Cutting off the top six feet was tricky, with the tree on its side and the trunk way up off the ground and springing back every time you hit it. I got it done, finally. The bottom half of the tree looked sickening lying there, like the body of a deer you’d killed to take the head and feet for a coat rack. We dragged the shapely treetop down the hill and left the rest behind. Not wholly without compunction, at least on my part. Just without compunction that did any good.

5

When we got back to Martha’s house, there wasn’t much left of the day but some orange-pink sky off in the direction of Hamilton Avenue. I had a headache from squinting into the sun. We’d stopped at a Lum’s on the way back, and I was able to get a couple of beers (in other words, three), which took the edge off things a little. To avoid talking about the immediate future — not, I swear to God, to nag — I’d brought up college one more time. He said he’d been thinking about Berklee, as in Berklee College of Music, and of course I thought he was saying Berkeley, as in the University of California at . So there was a big go-around about that, where I was saying he didn’t have the grades to get into Berkeley and he was saying what did Berklee care if he’d gotten a C-minus in Ancient and Medieval. Oh, I’d heard of his Berklee, just wasn’t thinking. It sounded like Danny, all right: trade school for musicians. What, I wondered, was the aspiration: to be in the house band on David Letterman? He had my blessing, I told him. (For what that was worth.) As long as he was really being honest with himself about his ability, I told him, and as long as that was what he really wanted to do. So nonjudgmental. Though come to think of it the artist’s life had got my father a lot more than the drudge’s life had got me. I mean, at least you could still find an early Francis Jernigan — they usually chose Arrangement 3 —poorly reproduced in a few books. My best shot at having made a contribution to humanity would be giving Danny a couple of unharassed years in which to play scales. But Christ, did he even remember how to read music? He’d stopped going to his guitar teacher after Judith died, claiming he wasn’t learning what he wanted to learn; since then he’d been spending hours a day in there playing God knows what through the Rockman and back into his own head. Well, fine: that showed dedication. Though that’s probably not all it showed. But wasn’t a place like Berklee going to demand some sort of basic proficiency? And, horrible thought: wouldn’t he need a recommendation from the music teacher at his high school, and wasn’t that Martin Sanders?

I worried about these things while driving back to New Jersey, as Danny napped, or feigned to nap. Then I worried about other things. Apparently I hadn’t imbibed much tranquillity from being up on a quiet hilltop. Imbibe. I wanted to fucking imbibe something all right.

Martha’s Reliant, as usual, was gone. I turned off the engine, and Danny, a bit theatrically, opened his eyes. “We’re back,” I said. “Like Nixon.”

He made no move to open his door.

“So Dad?” he said. “We’re just going to stay here and go along like we were? Do Christmas and everything?”

“I guess so, Dan,” I said. “For now at least. I can’t think what else to do, can you? Unless you just feel like, I don’t know, packing your stuff right now and just lighting out. I’d do it, if that’s what you felt like.”

“Okay, thanks,” he said. “That’s all I wanted to know.” He opened his door and got out.

“Hey,” I said. “Wait a sec.”

“I’m going to go in and see if Clarissa’s home,” he said. “I’ll help with the tree after if you want.”

“Don’t knock yourself out,” I said when I was sure he was out of earshot. Then I just sat there until it got too cold to sit there. Whatever that means. I suppose it means until the discomfort from the cold seemed worse than the other discomfort.

I dragged the treetop around back to the toolshed, found a handsaw and cut the trunk off straight where I’d mangled it with the ax. I also found a galvanized bucket, which I brought into the kitchen and filled with water. I set it outside by the kitchen door and balanced the tree on it, bottom branches resting on the rim, lopped-off stub of trunk down in the water. Dead but drinking deep. Now what we needed was a Christmas tree stand and we’d be all squared away here. Probably be easier just to go buy one instead of poking through the whole damn house looking for where Martha kept Christmas stuff. What could a thing like that run you, five ten dollars?

Thing was, I suddenly didn’t feel up to dealing with the mall and trying to find a Christmas tree stand in Caldor’s or some God damn place, with the people and the Christmas music and lines at the registers snaking back so far you couldn’t push a carriage around the front of the aisles. What I felt like doing was going to the liquor store and calling it a day.

I knew I should at least get something and clean the pine pitch off Martha’s saw. Gasoline, maybe? I always kept a hose in my trunk for emergencies; I could siphon a little out of the tank. But.

That headache wasn’t getting any better.

And I suppose, judging by what I found myself doing next, other stuff must have been bothering me that I wasn’t quite coming to grips with.

I went into the bathroom and took the last two Advils in the bottle, that’s how it began, and then two of Martha’s Pamprins. I was afraid to take the Pamprins, but that head really hurt, and I reasoned it out as follows. Once, years ago, I’d taken one of Judith’s birth control pills to stop her from taking it because I was sure they were killing her. This was back before people noticed that so many other things were also killing women. Nothing had happened to me from taking the birth control pill — I mean, I didn’t grow tits and my dick didn’t shrivel — so probably Pamprin was all right too. Then I went to the kitchen, feeling as if I were watching myself doing all this, to see what alcohol there was. Zilch, as I knew already. I would have to go out. I couldn’t go out. In the refrigerator I found one beer. Drank it in four swallows, then went back to the bathroom and took six more Pamprins and drank what was left of a bottle of Nyquil.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Jernigan»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Jernigan» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Jernigan» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Маргарет Миллар - The Iron Gates [= Taste of Fears]](/books/433837/margaret-millar-the-iron-gates-taste-of-fears-thumb.webp)