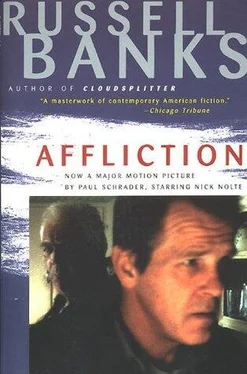

Russell Banks - Affliction

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - Affliction» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: HarperCollins Publishers, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Affliction

- Автор:

- Издательство:HarperCollins Publishers

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Affliction: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Affliction»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Affliction — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Affliction», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“About what?”

“About living here with me.”

“With you, maybe. With you and your father, though?”

“He’ll be all right,” Wade said firmly. “I promise you. I can control him. He’s like a child now, a kid who’s lost his mother, almost.”

“Are you talking about getting married, Wade? You and me? Like you were last night?”

“Well … yeah. Yes, I guess I am.”

Margie got up from the sofa and crossed the room to the doorway to the kitchen, where she stood looking at the old man. Slowly, he turned his head and looked back at her. He was like an old bony abandoned dog — skinny neck, dark sad eyes, slack mouth and slumped shoulders.

“How are you doing, Mr. Whitehouse?” she said.

His eyes filled with tears, and he opened his mouth to answer but was unable to make words come. He moved his head from side to side, like a gate, and lifted his open hands to the woman as if asking for coins. She walked forward and embraced him and stroked his tousled white hair. “I know, I know, you poor thing,” she said. “It’s hard. It’s very hard.”

Then suddenly Wade was beside her, and he wrapped his large arms around both of them, enclosing his father and the woman he would soon marry. He held the old man he would take care of from now on and the woman who would be his helpmate and partner in life, the woman whose presence in his life, in this old house way out in the woods, would help make Wade’s life a proper father’s life, one he could happily bring his daughter home to at last.

By the time I arrived at the house, three days later, Wade and Margie had already moved in. It was eleven in the morning, and the funeral was scheduled for one in the afternoon — at the First Congregational Church, Reverend Howard Doughty officiating.

Wade had been a busy fellow, I later learned. Sunday night, he had fixed the furnace and stayed over at the house with Pop, sleeping on the couch. Before going to bed, while Pop sat and drank by the fire in the kitchen, Wade went through our parents’ scattered papers and dug up, among other useful things, the documentation that he needed to make the insurance claim and finance the funeral, burial and gravestone. The next morning, he arranged all three. He notified the Littleton Register and the remaining members of the family — Lena and Clyde down in Massachusetts and Lillian and, of course, Jill, although he asked Lillian to “break the news to her,” as he put it, when she got home from school. Then he telephoned the dozen or so people in Lawford whom Ma would have wanted at her funeral, leaving it to them and to the newspaper to pass the word on to the outer circle of friends and acquaintances.

Though Wade managed to direct traffic at the school Monday morning, he did not go in to work — when he called to explain, LaRiviere was surprisingly understanding and sympathetic, Wade thought. By noon, he had put his trailer up for sale, and that afternoon he carted his and Margie’s clothes and personal belongings out to the house and stashed them in the larger of the two upstairs bedrooms. When Margie arrived, after work at Wickham’s, the two of them cleaned the house thoroughly. Ma’s effects — her clothes and personal papers and photographs and her knitting tools and yarns; there was not much else — they boxed and stored in the attic.

Tuesday morning, he directed traffic at the school and then drove to work as usual, and when he walked into the shop, LaRiviere told Wade, in front of Jack Hewitt and Jimmy Dame, that he could forget about well drilling for the rest of the winter, Jack could handle the work they had left till the ground froze, while Wade worked inside. “Learning the business from the business end,” LaRiviere said, with a beefy arm slung over Wade’s shoulder. Wade slipped from under the arm and stepped away, suspicious: this was a very different tone from the one Wade had long ago grown used to.

Jack glowered and lunged into the cold to finish the well they had started the previous week in Catamount, and Wade, as instructed, pulled off his coat and, clipboard in hand, started to make an inventory of all of LaRiviere’s material stock, equipment and tools. “I want to know my assets, Wade,” LaRiviere said in a confiding tone, “and I want you to know them too. I want to know what we need for a year’s work and don’t have on hand, buddy, and then I want you to sit yourself down and order it.” When Wade asked him if he could have Wednesday off, for the funeral, LaRiviere told him not to worry about it, and then added that from now on Wade was going to be paid a salary, instead of by the hour, same as if he were working a forty-hour week, whether he put in forty hours or not. And notto worry, buddy, about being paid for Monday and Wednesday this week: it was done. Wade almost heard him say “partner.”

He wants something from me, Wade thought, and I won’t find out what it is unless I smile and go along with him.

During his lunch break, Wade mailed his divorce decree and a check for five hundred dollars, borrowed the day before from Pop’s modest savings account, to Attorney Hand, and afterwards, by telephone from Wickham’s, he informed Hand that he would soon be getting married and was moving with his fiancée into his father’s “farm.” He also mentioned, as if in passing, his discovery that Lillian was having an extramarital love affair with Hand’s colleague Jackson Cotter, and Attorney Hand said that was a very interesting aspect to the case. “Tantalizing,” he said, and Wade could almost hear him smack his lips, the way he had almost heard LaRiviere say “partner.”

By Wednesday, the day of the funeral, so much had happened in Wade’s life that it seemed Ma had been dead for months.

Out at the house, the freshly plowed driveway and a specially cleared parking area by the side porch were full of cars, as if a celebration were going on. I parked my Volvo behind what I assumed was the minister’s car — a maroon station wagon with REV on the vanity plates — and got out and stretched and smelled the silvery wood smoke drifting from the kitchen chimney. I heard the sounds of distant gunfire crackle erratically against the wind in the pines, and I suddenly remembered that the forests and fields just beyond the house and in the hills and valleys for miles around were still dangerously populated by deer hunters.

There were a few cars and a blue pickup truck, LaRiviere’s, that I did not recognize and several that I knew— Wade’s Ford with the police bubble on top and Pop’s old pickup, still covered with snow and parked in the deep drift at the side of the house, as if stuck there permanently. I spotted the VW microbus that belonged to Lena and her husband, their fifteen-year-old recidivist hippie van plastered with born-again Christian bumper stickers instead of peace signs. The emblem of the Rapture — a black arrow shaped like a fishhook descending in a silver field against a vertical arrow ascending — and the cryptic question “Are You Ready for the Rapture?” and “Warning: Driver of This Vehicle May Disappear at Any Moment!” along with the more usual crosses and fishesin profile and mottoes like “Jesus Saves” and “Christ Died for Our Sins” were stuck all over the sides of the van, as if the vehicle were a huge cerulean cereal box promoting apocalypse and everlasting life and promising redeemable gift certificates inside.

Lena and her husband, Clyde, had made Christ their personal savior, apparently the result of a visit from Him — a type of house call was the way they explained it — one night of despair four or five years earlier, and while the chaos of their life had not changed one iota, it had gained significant meaning, since they and their five children were now devoted to the life of the spirit and the next world instead of to the body and this one. Their disheveled and deprived daily lives were now regarded as evidence not of incompetence, as in the past, but of their new priorities. I did not pretend to understand the nature of the conversion experience, of being “saved,” one way or the other, or the teachings of the Bible Believers’ Evan-gelistical Association, to which they belonged, but it was clear to me that whereas before they had been depressed and frightened, for what seemed very good reasons, such as poverty, ignorance, powerlessness, etc., they were now optimistic and unafraid. Of course, according to the pamphlets Lena mailed to me from time to time, what they were looking forward to was the imminent end of the world, to earthquake and famine, to seas turned to blood, to plagues of sores, to legions of demons and the writhing demise of the antichrist, events that those of us who were not scheduled for rescue by the Rapture might find even more depressing and frightening than poverty, ignorance and powerlessness.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Affliction»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Affliction» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Affliction» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.