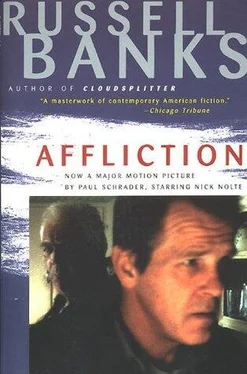

Russell Banks - Affliction

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - Affliction» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: HarperCollins Publishers, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Affliction

- Автор:

- Издательство:HarperCollins Publishers

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Affliction: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Affliction»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Affliction — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Affliction», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Wade took two more steps forward and leaned into the brightly lit office. LaRiviere looked up and wrinkled his broad pink brow in puzzlement, and as he started to open his mouth, Wade snapped his middle finger at him and said, “Fuck you, Gordon.” LaRiviere’s expression did not change; it was as if Wade and he were in different time zones. Wade pushed his cap onto his head, turned and left the office.

Five minutes later, he was up inside the flapping canvas cab of the grader, driving it across the parking lot and down the driveway to the road, the long narrow plow blade bouncing along under the high belly of the machine like a gigantic straight razor.

Jack Hewitt stood at the lip of the incline and peered across the tops of the trees through the dip in Saddleback all the way to Lawford Center. The wind had shifted slightly, or perhaps the falling snow had eased somewhat, for he could see the spire of the Congregational church and the roof of the town hall in the valley below. He might have been trying to figure out where among the distant trees his father’s house was located, when Twombley come puffing up behind him.

Red-faced and out of breath from the effort of trying to keep up with the younger man, Twombley was about to speak, no doubt with irritation, but Jack lifted one finger to his mouth and silenced him. Then, stepping off the edge of the low ledge, he leaned into Twombley’s ear and said, “Stay here, stand where I am.”

Twombley took two steps forward, peered over the edge at the lumber trail twenty feet below and the field of strewn boulders beyond it.

Jack came up alongside him and whispered that he was going to circle back around the ledge on the west. He would cut down to the trail through a stand of pines there and drive the deer back along the trail to where the animal would come into clear view just below Twombley and fifty yards to his left. He told him to make sure he was ready to shoot, because he would only have one shot.

Twombley unslung his rifle, checked the chamber and flicked off the safety. “What’d you see?” he asked.

Jack told him about the tracks and the moist dark-brown pellets of deer shit.

“Fresh?” Twombley said.

“Yup. And wicked big, too. This here’s your buck, Mr. Twombley. The one you been thinking about all fall, right?”

Twombley nodded and edged closer to the drop-off. “Get going,” he said to Jack. “You only got a little while if you want that extra hundred.”

Jack looked at the man for a second, and his mouth curled into a slight sneer. Then he turned abruptly away, as if to hide the sneer, and started walking toward the stand of pines that ran in a ragged line uphill from the ledge. On the farther side of the pines the ground sloped more softly, and the trail nearly flattened out for a ways, and there were several head-high heaps of dead branches and brush that had been stacked along-side the trail some years back by the lumbermen. Jack knew that the big buck was hiding in one of those brush piles, that he was lying down, listening to gunfire in the distance and the snap of a twig fifty feet away, sniffing for the sour smoky odor of humans, large brown eyes wide open and searching for any movement in his field of vision that did not fall into the familiar rhythm of a world without humans. Jack was adjusting, narrowing, his own field of vision, bringing his gaze to a sharp focus on the tangled heaps of brush so that he could determine which of the three hid the big deer, when he heard Twombley cry out, and he started to turn. At the same instant, he heard the gun go off, and he knew that the stupid sonofabitch had slipped and had shot himself.

He thought about it that way and that way only, and he walked slowly, angrily, back to the edge of the incline where Evan Twombley had stood, and he looked down at the man’s body splayed in the snow below him. He shouted at the body, “You’re an asshole! A fucking asshole!”

Twombley lay face down, with his arms and legs spread as if he were free-falling through space. His new rifle lay beside him, a few feet to his right, half buried in the snow.

Jack pulled out a cigarette and lit it and stuffed the crumpled pack back into his pocket. He dearly hoped the man was dead, stone cold dead, because if he was still alive, Jack would have to lug the stupid sonofabitch all the way back up to the truck and probably haul him all the way to Littleton. “Stupid, arrogant sonofabitch,” he said in a low voice, and he started down, slowly, carefully, to find out if indeed, and as he hoped, Evan Twombley had killed himself.

Not until he reached Toby’s Inn did Wade — hunched over the large steel steering wheel in the painfully cold windblown cab of LaRiviere’s blue grader — finally catch up to Jimmy Dame in the dump truck. This was as far as the town plows went; they and the state DPW plows met and turned around at Toby’s and went back to their respective territories. Jimmy had zipped a few complimentary passes over Toby’s lot and was sitting in the truck in the far corner of the lot, enjoying coffee and Danish from Toby’s kitchen and watching Wade as — compulsively and with great difficulty, because of the size and awkwardness of the grader — he finished scutting Jimmy’s residue off to the side of the rutted parking lot.

Jimmy liked watching Wade try to use the grader as if it were a pickup with a flat plow on the front, driving the enormous and grotesquely shaped vehicle forward ten feet, then backward ten feet, short half turn to the right, short half turn to the left, wrenching that huge steering wheel like the captain of a ship trying to avoid an oncoming iceberg. It was crazy, Jimmy thought, and Wade was crazy. He did it every winter: got to LaRiviere’s shop late the first day of a snowstorm because of directing traffic at the school, then got stuck with the grader, which naturally pissed him off, since it was like being in an icehouse up there, except that then he’d drive the damned thing like he was glad to have it, really pleased to have the chance to show folks what this here grader could do when it came to plowing snow. After knowing him all his life, Jimmy still did not know if he liked Wade or not.

Jimmy Dame, like Jack Hewitt, was one of Wade’s helpers on the well-drilling crew. Wade was the foreman and had been for a decade. But when they were not drilling wells, they all three tumbled to the same level and were paid accordingly. When the ground froze solid and well drilling was no longer feasible, LaRiviere put them to work first on snowplowing, and when that was done, on maintaining equipment, vehicles, tools and materiel, and when everything LaRiviere owned had been brought up to his fastidious snuff, which is to say, in as-new condition, and the garage and toolboxes and storage bins had been swept and squared as smartly as a marine barracks, LaRiviere promptly laid off Jimmy. A few weeks later, he laid off Jack, and last of all, Wade. This usually occurred late in February, which meant that Wade was out of work no more than six weeks.

It was hard to know what factors determined LaRiviere’s policy of laying off first Jimmy, then Jack, then Wade. Both Jimmy and Wade had worked for LaRiviere since getting out of the service, and Jack had come on only three years ago, so it was not seniority. And it was not age, either, as Jimmy was two years older than Wade, twenty-two years older than Jack. And it was not on the basis of who had the widest range of skills, because Jack could type and Wade could not, and when given the opportunity to do it, Jack liked office work, whereas Wade felt worse than peculiar, he felt downright terrified, when, as inevitably happened on a cold dark snowy day in February, LaRiviere asked him to come into the office, get out the calculator and an architect’s scale and take measurements off a blueprint stretched across the drafting table and help prepare a bid on some spring work for the state. Wade pulled off his jacket and cap and sat on the stool and went to work, listing sizes and lengths of pipe and fitting required, converting those figures into man-hours, calling Capitol Supply in Concord for prices, clicking away on the calculator and every time, without fail, coming up with totals that were so much over or under what simple horse sense told him the job should cost that he felt compelled to start the process all over again. The second time through, his totals once again were so far off, and in the opposite direction of the first set, that Wade could trust nothing — not the drawings and not the architect and engineer who made them, not the calculator, not the supplier and, most of all, not himself. He knew the work, the figures for the materials were all fixed in black and white, and he could read blueprints with ease; but somehow, every time he added up his figures he fumbled, skipping a whole column of figures one time, doubling sums the next. Was he brain-damaged, missing a few crucial cells someplace? Was there something wrong with his eyes, some mysterious affliction? Or was he just made so nervous by LaRiviere sitting a few feet away from him that he could not concentrate on the rows of numbers in front of him? Usually, after a dozen failed attempts to come up with an estimate that approximated his commonsense knowledge of the cost of a job, Wade would start to growl audibly from his stool at the drafting table, a low rumbling canine growl, and LaRiviere would look up from his desk, blink his tiny pale-blue eyes three or four times and tell Wade to go on home for the rest of the winter.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Affliction»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Affliction» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Affliction» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.