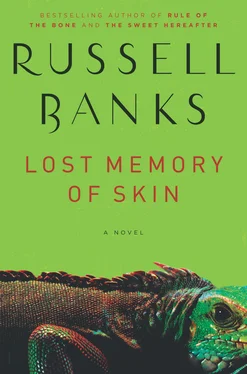

Russell Banks - Lost Memory of Skin

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - Lost Memory of Skin» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Ecco, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lost Memory of Skin

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ecco

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lost Memory of Skin: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lost Memory of Skin»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

and

returns with a provocative new novel that illuminates the shadowed edges of contemporary American culture with startling and unforgettable results.

Suspended in a strangely modern-day version of limbo, the young man at the center of Russell Banks’s uncompromising and morally complex new novel must create a life

Lost Memory of Skin — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lost Memory of Skin», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He can’t set up camp in the parking garage at Terminal G or sleep on one of the benches in the waiting area inside. The airport’s a favorite cul-de-sac for homeless crazies, drug addicts, and alcoholics to panhandle harried travelers who are usually flush with cash and more or less confined to the terminal waiting for their delayed flights to arrive or depart. People like that are easily hit for a buck or two just to make the panhandler go away, since they’re stuck at the airport and can’t go away themselves. The homeless crazies, addicts, and alcoholics end up nodding out or falling asleep on a modernist stainless steel bench inside the terminal stinking up the place or else they look for an unlocked car in the garage or failing that break into a locked car where they can hole up till the owner comes back from his trip. Which is why there are so many cops patrolling the area. The Kid would be busted in an hour for vagrancy and sent back to prison for violating parole.

That leaves the Great Panzacola Swamp. The vast grassy marshland is a fourteen-thousand-square-mile national park that sprawls across the entire southwest quarter of the state, extending all the way east into Calusa County to where it was partially drained a generation ago by a concrete grid of thirty-foot-deep canals creating the cane fields, citrus groves, and truck farms that bump up against the expanding suburbs and tract-house developments of Greater Calusa. West of the suburbs, fields, farms, and groves, there is a sizable chunk of the swampy waters, lakes, slow shallow streams, mangrove islands, low hummocks, and grasslands — some five hundred thousand acres of the Panzacola National Park — that remains within the borders of Calusa County. The Kid can legally reside there.

Though less than thirty miles from so-called civilization, the swamp is home to alligators, small deer, the last of the American cougars, and hundreds of species of birds. Out where the freshwater streams and the shallow run-off from the lakes farther north mingle with the saline waters of Calusa Bay and the Gulf there are diminishing numbers of crocodile colonies and manatee pods. Also in recent years many Calusans have released into what looks to them like the wild exotic pets grown too large for their cages or too dangerous for domestic life with humans. The swamp has become the home away from home of twenty-foot-long Burmese pythons and other large Asian, African, and South American snakes, huge snapping turtles captured as babies in Georgia and Alabama ponds, pet wolves, feral cats, parrots and cockatoos, and in a few cases monkeys, macaques, gibbons, and at least two pet chimpanzees grown from cute little humanoids into powerful destructive adults that a year ago had to be shot by park rangers for attacking a group of their Homo sapiens cousins visiting the park from abroad.

At the ranger station located near the entrance to the park you can buy a ticket for a thirty-minute tour-boat ride through a small part of the swamp and out into Calusa Bay to watch the sunset. Or if you prefer to penetrate to the heart of the swamp on your own you can rent a canoe by the hour for the day. If you want to stay longer than a day but are not eager to sleep in a tent at one of the flea- and mosquito-infested campsites you can rent one of the half-dozen small underpowered flat-bottomed houseboats, stock it with water, food, iced beer or wine, fishing gear, and plenty of sunscreen and bug spray and with a topographical map of the entire multimillion-acre park in one hand and the tiller in the other you can disappear into the depths of the swamp for days or weeks or even longer if you can afford the rent.

Though he’s never been to the Great Panzacola Swamp in person and doesn’t know much about anything that he hasn’t experienced in person the Kid knows all this. He learned about the swamp and the houseboats from the Rabbit one night back when he first pitched his pup tent under the Causeway. Still unused to the noise of the traffic overhead, the filth, stench, and crowdedness of the place and the sometimes erratic scary behavior of the other residents, he was grousing to the Rabbit who was the only one living down there who had befriended him and didn’t seem to want anything from him in return. The Kid whined that there’s got to be a better place than this rat hole where they could legally reside.

The Rabbit told him there wasn’t. But if they had enough dough they could rent a houseboat and live in the Great Panzacola Swamp and still be in Calusa County. Nobody hassles you out there, Kid. They got a store at the ranger station where you can buy what you need. You can even rent a post office box there for your Social Security check or if you’re on welfare. Once a week or so you come in off the swamp, pick up your mail and restock your supplies, fill up the gas tanks and head back out the same day. ’Course, it’s probably pretty boring after a while. And there’s all kindsa dangerous snakes and animals out there. And it’s buggy. I mean, Kid, it’s a fucking swamp! They probably got malaria out there. But nobody can bust you as long as you can pay your rent for the boat and obey the park rules.

The Kid asked him what the rules were and the Rabbit said he wasn’t sure but figured you couldn’t toss any trash overboard or pick the flowers or use firearms or make campfires except in designated spots. That sort of thing. He said he heard there were still a few Indians living deep in the swamp way west and north of the Calusa County line, descendants of the Seminoles and escaped slaves who fought the white Americans to a standstill back in the nineteenth century getting by on hunting and fishing for food, living in hidden huts and tents on the mangrove islets and now and then guiding fishing parties out of the lodges located near the highways and in the small towns on the far edges of the park. He thought they signed a peace treaty years ago that gave them some special park privileges. He heard there were a few fugitives hiding out in the swamp too. Outlaws, Kid. Sort of like us. Only without electronic GPS anklets, so nobody knows where they are. If you cut the fucking thing off your leg, nobody’d know where you were, either. The cops’d never think of looking for you in the swamp. They’d just think you booked for Nevada or somewhere in the West. They’d put out an APB to have you picked up and wait for you to turn up busted for vagrancy in Salt Lake City or someplace.

The Kid was interested in the idea. That sounds awesome, man! I hate this fucking bracelet.

It’s an anklet, Kid. And if you cut it off you’d be an outlaw too, the Rabbit pointed out. A fugitive. You’d have to live in the swamp the rest of your fucking life. For me, no big deal maybe, but for you, different. If you ever wanted to come back to civilization for a visit or to get laid you’d get busted the first day just on suspicion of being alive, and they’d nail you for cutting off your tracker and you’d be back in the can. ’Course, as long as you kept your tracker on and the battery charged, which you could probably do at the ranger station, and didn’t go beyond the county line, they couldn’t legally stop you from living on a boat in the swamp.

The Kid asked him if he was up for it. Why not? They could rent one of those houseboats and live in the swamp together. It had to be an improvement over living in a tent under the Causeway.

The Rabbit laughed and agreed, sure, it would be a decided improvement. But forget about it, Kid. Those houseboats go for like fifty bucks a day. Maybe more. Who’s got that kinda bread? Not me. And not you either.

But that was then. This is now. The Rabbit may be gone to the bottom of the Bay with Iggy, but thanks to the Professor’s upcoming suicide, the Kid’s got plenty of bread now.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lost Memory of Skin»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lost Memory of Skin» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lost Memory of Skin» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.