He sets the tray onto the folding stand beside the table and very carefully removes first O. J.’s knife, then the dishes and the rest of the silverware and the empty glasses. When he nervously reaches for O. J.’s wineglass the man places his brown football-size hand over it and shakes his head no and the Kid quickly backs off.

Sorry sorry. Very sorry.

I’ll have another glass of the Rhône.

Yessir. I’ll tell your waiter.

The man the Kid thinks is Spanish says, Bring me half a pear .

O. J. laughs and says, Fucking half a pear! Why do you want only half a fucking pear? Get a whole one, for chrissakes, and eat half if you only want half a fucking pear.

I only want half a pear. I wanted a whole fucking pear I’d order a whole fucking pear.

O. J. says to the Kid, Bring my fastidious friend here half a fucking pear.

Yessir.

Dario is standing at the headwaiter’s desk by the door going over lunch reservations. As the Kid passes with his tray of dishes and silver and glassware from table seven he stops for a second and says, O. J. wants another glass of wine. Rhône. Want me to bring him his wine?

I’ll take care of it. Fucking guy never buys a decent fucking bottle himself unless somebody else’s paying. Like he expects to get comped his whole fucking life.

And there’s an asshole over there who wants half a fucking pear.

At that moment the asshole — the Spanish-looking guy with the bad hair — passes behind the Kid on his way to the men’s room. The Kid realizes he’s been overheard.

Oh yeah and this gentleman wants the other half!

The gentleman nods, smiles, and moves on to the men’s room.

Dario places a hand on the Kid’s shoulder. That “gentleman” is the Nicaraguan consul.

No shit? The guy with O. J.?

No shit.

I thought in Nicaragua everyone was a soccer player or a hooker.

Dario gives the Kid a cold look. Then he turns his attention back to the lunch reservations. In a low voice he says, You some kinda wiseguy? My wife’s from Nicaragua. You know that. Everybody works here knows that.

Jeez, Dario, I didn’t even know you were married. What team’d she play for?

Dario takes a step back and squints at the Kid. Is he serious? Is he putting me on? Is he insulting my wife? Or me? The Kid confuses Dario. He’s confused him since the day he walked in and asked for a job that almost always went to a Honduran or a dry-footed Cuban off the boat or a wet-footed Haitian with phony papers. A normal-looking little white American guy in his twenties with a high school diploma, a type that almost never wants to bus dishes except temporarily as a way to become a waiter. He took the Kid’s application anyhow and ran the usual background check. It turned out the Kid was a listed sex offender on parole and was wearing an electronic ankle bracelet. Dario got the picture. But the Kid didn’t seem mentally retarded and he spoke decent English and a little Spanish so he went ahead and hired him anyhow. He figured because of his record and the risk of being sent back to jail he wasn’t likely to cause trouble or steal anything.

He called the Kid in and told him he knew about his past. The Kid said it was all a stupid mistake, he was innocent of everything, he was set up. It looked like he was going to break into tears right there in Dario’s office and Dario felt sorry for him which he rarely felt for anyone especially someone he was interviewing for a job. In the past he’d hired ex-cons, recovering alcoholics, and addicts just out of rehab, men and women he knew were illegals with doctored documents and they usually made good dishwashers, pot scrubbers, and busboys at least for a few months or a season until they fell off the wagon or reverted to their old petty criminal habits or got busted by the INS or Homeland Security and deported or locked up. He figured the shadow hanging over the Kid would keep him in line. Which it has.

But that was ten months ago and the Kid is starting to get on Dario’s nerves. Not for anything he does as much as for what comes out of his mouth. The Kid is a good worker but he’s also a wiseguy. A smart-ass. You never know what he’s going to say or not say. He makes Dario nervous as if the Kid doesn’t give a damn about his job and is periodically tempting Dario to fire him. This is one of those times, Dario decides. Enough already.

Kid, put your tray in the kitchen and take off your jacket and go home.

What?

You heard me. You’re through. Come by the end of the week for what you’re owed.

Why are you firing me?

You got a fucking big mouth. You don’t show respect.

Dario sniffs his carnation, turns away from the Kid, and walks toward the bar. I gotta get the wife-killer his fucking cheap glass of bar wine. Don’t be here when I get back.

Okay. I won’t.

The Kid slowly hefts the loaded tray to his shoulder and heads for the kitchen. To himself since no one’s listening anymore he says, I don’t know where I will be though. I got nowhere left to go.

NOWHERE, EXCEPT BACK TO THE CAMP beneath the Causeway. So he goes there. By the time he steps over the guardrail and cuts down the sharp slope to the concrete island below it’s late afternoon and the camp is shrouded in semidarkness. A few of the rousted residents have returned and are struggling to prop their shanties back up and hanging plastic sheeting over jerry-built frames of PVC tubing and cast-off lumber but otherwise the place is mostly deserted. They too have nowhere else to go. They ignore the Kid and he ignores them. Nothing new — that’s how they usually act. Like they’re covered with shame and are ashamed of each other as well. Him included.

The camp looks like a small tornado blasted through — clothing and papers and blankets lie scattered in no discernible pattern, shacks and shanties have been turned into piles of rubble, tents have been pulled down and tossed into rumpled heaps of canvas and torn pieces of plastic. The Greek’s generator lies on its side half in the water and half out. A strong shove would dump it permanently into the Bay. The few returning survivors of the raid move slowly and silently in the gloom as if merely trying to make the best temporary use of the wreckage they can but with no evident ambition to restore what they built before the raid when it was practically a village down here, a settlement of men, grim and minimal and squalid but an extension of the city nonetheless as if the city had deliberately colonized this dark corner of itself with its outcasts.

A couple of residents are fishing for their supper from the edge of the island. Someone in the cavern beneath the far on-ramp has set a grill on bricks and built a driftwood fire and is boiling water in a pan probably for spaghetti or a one-pot meal from a box. These are the only signs of domestic intent.

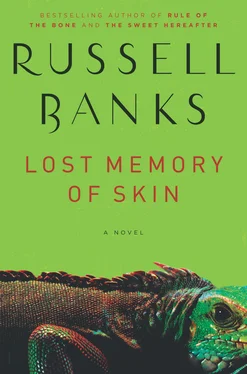

From a short distance the Kid spots his bike still chained to the pier where he left it and his tent collapsed in a pile next to it. No sign of Iggy — which he’s desperate enough to take as a good sign. This is not the same as optimism. The Kid is definitely not an optimist. Even so he thinks maybe Iggy somehow escaped and is hiding in the shadows or under a pile of wreckage waiting for the Kid to come back for him. It’s possible but not very likely that the cops called the SPCA or some kindly animal rescue organization and they unhooked his chain from the cinder block and hauled him off to Reptile Village where he’s already found himself a cave to sleep in and a tree to climb and a friendly female iguana to warm his cold reptilian blood.

Читать дальше