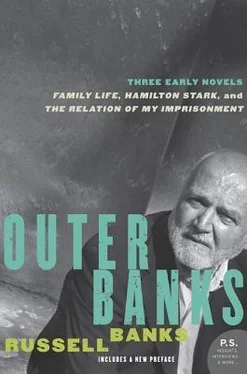

Russell Banks - Outer Banks

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - Outer Banks» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Outer Banks

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Outer Banks: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Outer Banks»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

and Family Life: Hamilton Stark: The Relation of My Imprisonment:

Outer Banks — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Outer Banks», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“A little,” Ham said somberly.

“A lot, I bet.”

“Yes, a lot.”

“Did you learn something?”

“Yes. I guess so.”

“What?”

“To stay away from your fighting cocks?” he tried.

“No, not exactly,” his father said to him. “I don’t want you to be afraid of them, boy. And if you just stayed away from them, that’s all you’d be. Afraid. I want you to respect them. Do you understand the difference?” his father asked. “Respecting something that can hurt you is different from just being afraid of it. And to respect the fighting cocks you’re going to have to deal with them face to face. Maybe that way you’ll get over being afraid of them,” he promised. “Do you understand?”

“No … not really. Maybe I do.”

“Well, it doesn’t matter. You will,” his father told him. And then he told him that he had a “job” for him. Every morning from then on Ham would have to feed and water the hens and roosters, including the fighting cocks. He would start the next morning, when they would do it together, so he’d know how much corn to give them and how to handle the fighting cocks so they wouldn’t hurt him or escape from their cages. But after that he would have to do it alone. It was a “job,” his father explained, because he was going to be paid for it — fifteen cents a week, every Sunday morning before church.

But Ham could not stop being afraid of the fighting cocks. He might have if one morning early that first week Gene, the yellow one, had not nipped off a piece of the meat of his hand between thumb and forefinger. After pitching corn into Gene’s cage, Ham simply had not been fast enough in pulling his hand away, and the bird had got him.

His father had showed him how to do it, but true safety depended on speed, so he was not sorry for Ham. “If you’d done it the way I showed you, he never would have got you. You’ve still got to learn how to respect those birds. It’s not fear that’ll get your hand out of that cage in time. It’s respect.”

So Ham had concentrated on speed that he believed was derived from respect rather than from fear. He practiced on old Henry, the Rhode Island red, whom he knew he respected and of whom he had no fear whatsoever. He would walk into the henhouse carrying a can of corn, and extending a handful of it, he would call, “Here, Henry! Here, Henry! Corn, Henry!” and the bird, head cocked to one side like a partially deaf old man, would stalk somewhat wobbly toward the boy, and when his beak was a few inches from Ham’s hand, the boy would throw the corn onto the cold, bare ground, and Henry would dive for it.

If that’s what respect feels like, Ham thought, I like it. I especially like it better than being frightened.

Nevertheless, when it came time to feed the fighting cocks, the only speed Ham developed seemed to depend on fear. He was terrified of the birds — their endless anger, their suddenness, the weapons they carried. Whenever he neared their twin cages in the corner of the henhouse, his hands started to throb, his arms grew weak, and his back and shoulder muscles stiffened. One night he dreamed that as he opened the sliding door to feed Jack, both cocks had flown out and had furiously attacked his face, hunting madly for his eyes, and he had awakened screaming. When his mother tried to get him to tell her about the dream that had frightened him, he had refused to tell her. “I can’t remember,” he had lied.

Throughout the fall, Ham struggled to overcome his fear of the fighting cocks. The birds had grown used to his feeding and watering them every morning, so they no longer treated his arrival as a chance to attack or escape but instead waited patiently for their food, which, as soon as Ham had slid back the door to their cage, they greedily devoured, swinging their heads like short hatchets swiftly chopping the corn to bits.

In spite of this change in the birds’ expectations regarding Ham’s arrival, a change that in some sense gave them a measure of reliability and even a type of kindness toward him, he was still frightened of them, and he continued to move his hand with the food or water dish in and out of their cages as if he were plucking hot coals from a fire. He tried to respect them for their new restraint, but he couldn’t. He knew that the reason they were no longer flying at him was merely because they were hungry and had realized that it was his job to feed them.

They didn’t like their cages, especially when every day the hens and old Henry left the henhouse to scratch in the fenced-in yard outside. Also, the daytime proximity of Henry and his harem amiably socializing together seemed to enrage the fighting cocks, and every hour or so the pair would crow angrily at the other birds. As always, Henry continued to crow only at sunrise and sunset.

Ham’s father no longer talked about arranging cockfights and making lots of money from Jack and Gene. Ham’s mother explained that it was illegal anyhow. “And with good reason,” she had said angrily, but that was as much as she would say.

Every Sunday morning, before Ham and his mother got into the pickup truck and drove to the church in the Center, his father, who never went to church except at Christmas and Easter, paid Ham his fifteen cents — a dime and a nickel. “Put the nickel in the collection plate. Save the dime,” he told his son each time he paid him.

And Ham did save the dimes. The first Sunday he had been paid, he had taken the calendar down from the kitchen wall, and studying it a while, had calculated that by Christmas he would have saved almost two dollars, which, he decided, he would use to buy Christmas presents — for his parents and his cousins. Until then, he had been too young to have any money of his own, and he had not been able to buy any presents for anyone. Like a baby, he had been forced only to accept. But now that he had a job, he was not a baby anymore.

Then one Sunday morning in early December, after it had snowed heavily all night long, the milky, overcast sky in the morning and the dense silence of the first snow caused everyone in the family to sleep a few minutes later than usual. Even old Henry overslept and didn’t crow until almost eight o’clock — a half-hour late at that time of the year.

In a rush to feed and water the birds, Ham neglected to close the door to Jack’s cage with the snap that locked it. He hurried back through the foot-deep snow to the house, and while his father shoveled out the long driveway to the road, he gulped down his breakfast and got dressed for church. Before he and his mother left, his father paid him.

Later, when they returned from church and walked into the kitchen, his father said somberly to Ham, “Leave your coat on, boy. I want you to come out to the henhouse and see something.” He got up from his chair, put on his own coat and hat, and led his son outside and along the narrow path he had shoveled to the henhouse.

At the door to the henhouse, his father stopped and lit a cigarette. Then he said, “Go on in,” and Ham swung open the door and stepped inside.

The cold-eyed fighting cocks, locked inside their cages, were striding rapidly back and forth. Across from them, in the farthest dark corner of the henhouse, the hens were huddled silently together in a rippling mass, all of them facing the wall. And in the center of the packed dirt floor lay the body of old Henry, shredded at the breast and head, with a flurry of blood-tipped feathers scattered about it on the floor.

Ham turned around and stepped back outside to where his father stood smoking and waiting for him. The sky had begun to clear, and the snow glared brightly in the sunlight, so that for several seconds Ham could not see.

He heard his father say, “You know what happened, don’t you?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Outer Banks»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Outer Banks» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Outer Banks» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.