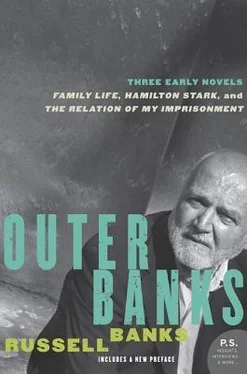

Russell Banks - Outer Banks

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - Outer Banks» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Outer Banks

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Outer Banks: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Outer Banks»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

and Family Life: Hamilton Stark: The Relation of My Imprisonment:

Outer Banks — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Outer Banks», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I will tell you how I arrived at such a notion.

It fascinated and amazed me that a person born into squalor such as this could grow to his adulthood in that same neighborhood and yet could possess qualities which, upon close examination, could be seen as both wisdom and passion.

How was that possible? I asked myself.

And then I asked myself if A. possessed these qualities (wisdom and passion), in fact, or if he were merely peculiarly mad. But on the other hand, I countered, even if he were peculiarly mad, and if his peculiar madness, which sometimes took forms that could be construed as wisdom and passion, happened to be a condition necessary for the man’s mere survival — after having been born and raised in social circumstances that ordinarily dun a human being to death, turning him wormy with passive, quiet desperation long before he reaches adolescence — why, then madness was indeed wisdom, and to cling to such madness was passion!

That way, spiritual survival became, in my eyes, self-transcendence, practically an evolutionary move on the part of the organism. The question of love, its mere possibility, a question that had haunted me in my long consideration of A.’s character, thereby became wholly irrelevant. He was beyond offering love, above it and superior to it — at least the kind of love that I, from my indulgent background, had learned long ago to value in myself and seek from others.

This was, for me, a welcome series of insights, and I felt greatly relieved, as if from a dreaded, demeaning chore, like cleaning out a septic tank. I thought: Any person whose life provides us with that particular relief is worth writing a novel about. For who among us has not wished to be freed of his need to love and be loved?

IT WAS WITH considerable excitement, then, that I approached the turnoff from the paved to a dirt road, practically a trail, that led through a quarter-mile of approximately flat and unkempt fields to A.’s home. The fields on both sides of the deeply rutted road, lined with slowly collapsing stone walls, had retreated to furzy bushes and scrambling tangles of wild blackberries, sumac, and poison ivy. Scattered over the fields in no discernible pattern were ten or twelve rusting shells of windowless cars and trucks, some of them further decomposed and more nearly destroyed than others, also several farm vehicles — harrows, plows, cultivators — a one-handled wheelbarrow, an outhouse lying awkwardly on its side, rusty bedsprings and swollen mattresses spitting yellowish stuffing onto the ground, a pile of fifty-gallon oil drums, an engine block and a transmission housing, both lying atop a child’s crushed red wagon which lay atop an American Flyer sled in splinters, next to a refrigerator (with the door invitingly open, I noticed), and a red, overstuffed couch which had been partially destroyed by fire. None of this wreckage was new to me. I had observed, enumerated, and reflected on all of it many times, both alone and with friends, especially with my friend C. (about whom more later).

The fields and the road were all part of A.’s property, but a stranger, noting the broad, carefully maintained lawns, gardens, house and outbuildings which spread out from the closed gate at the end of the cluttered fields, would surely infer two separate and probably quarreling owners, one for the fields and badly maintained roadway, another for the house and grounds. But that was not the case. A. was fastidious and energetic, even compulsive, about the maintenance of the house and the yards, gardens and outbuildings that surrounded it. The region that lay beyond the white, iron rail fence, however, he cared for not at all, even though some seven hundred acres of that region was his private property, had been deeded to him with the houses and outbuildings by his parents.

Actually, it was fortunate that so much of the world beyond the fence was A.’s private property, because for years he had been tossing his garbage over that fence, throwing his rubbish, all his used-up tools, vehicles, furniture, even his old newspapers, over the fence and into the field. Every now and then, perhaps once a year, depending on domestic changes, he rolled out his bulldozer, took down a section of the fence, and shoved the rotting garbage and trash roughly toward the main road and away from the house, to make more room near the fence. It was a casual operation. The vehicles stayed pretty much where he had left them, and he usually left them where they had got stopped, either because of running aground on a huge boulder, of which the field had an abundance, stalling or coughing out of gas, getting stuck in the mucky, tangled ground, or ramming into another car or truck from a previous year’s trash. He used his vehicles until they were too weary and broken to drive any farther than to this odd burial ground, and he always tried to make that last drive as exciting as possible. Then he would hitchhike twenty miles to Concord, where there were half a dozen automobile dealers, and buy a new vehicle, usually a different type from the one he had just interred — a pickup truck if last year’s had been a sedan, a station wagon if a convertible. Because of the intense way he drove them, his new vehicles rarely lasted longer than a year.

Similarly, whenever he disposed of furniture, tools, garden implements, waste or rubbish of any kind, he took from the act whatever last pleasure he could wring from it — making bets, and usually winning them, that he could lift and throw a sofa over the fence, or hurl a transmission housing from his pickup bed onto a pile of old toys, and then an engine block onto the transmission housing; or that he could carry a refrigerator in a broken wheelbarrow for a quarter of a mile over a rough surface under a hot August sun. Afterward, to complete the act, he liked to sit up on his porch, usually in the admiring company of a friend or one of the local adolescent boys he permitted to hang around him, and while guzzling Canadian whiskey and ale, fire his rifle at the new trash. He shot his rifle at many things, animate and inanimate, but he always seemed to enjoy it most when he was shooting at the things he had used up and thrown out.

On this particular day, a blotchy, glutinous gray afternoon with a cold rain lightly falling, as I neared the gate where the road ended and A.’s wide, paved driveway began, I noticed a high, wobbling stack of what appeared to be new furniture — a Formica-topped kitchen table and four chairs, a double bed with bookcase headboard and matching dresser, several table lamps, and two or three cardboard cartons filled with pastel articles of clothing and possibly curtains and bedding. This carefully constructed stack, with all the articles balanced and counter-balanced, was located a few feet from the fence and about twenty feet from the roadway, and I had never seen it before. I assumed, therefore, that these were his fifth wife’s leavings, her effects, an assumption which later proved correct.

I got out of my car, walked up to the gate, unlatched it, and swung it open. I could see A. in the distance, sitting on the porch of the house at the far side, swinging slowly in the wood glider. Neither of us waved or signaled to the other. That was customary. I returned to my car, drove it through the gate, got out again, and closed the gate behind me, as I knew I was supposed to do, and then drove up the long, curving driveway past the smooth, freshly greening lawns to the house, and parked next to the house on the side opposite the porch, where the driveway ended, facing the entrance to the small barn, which under A.’s care had been converted after his father’s death into a modern garage and workshop. Behind the house loomed the humpbacked profile of the mountain, Blue Job, adding its shadow to the day’s gray light and casting the darker light like a negating sun across the house and onto the fields in front.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Outer Banks»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Outer Banks» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Outer Banks» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.