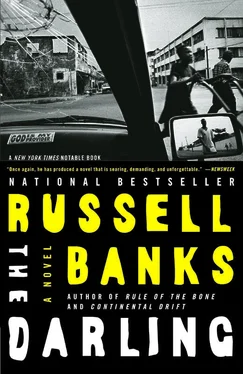

Russell Banks - The Darling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Darling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Darling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Darling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Darling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of Hannah Musgrave, a political radical and member of the Weather Underground.

Hannah flees America for West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends of the notorious warlord and ex-president, Charles Taylor. Hannah's encounter with Taylor ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah's family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

The Darling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Darling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I steeled myself and slowed the car and pulled up before the closed gate. I didn’t remember closing the gate, but must have, to keep the dogs inside the yard. But had I locked it? I wondered, for I saw in the headlights that the padlock had been hooked into the hasp and was snapped shut.

I got out of the car and walked to where Woodrow had been murdered. There was a splash of moonlight through the trees on the ground where he’d been forced to kneel and a pool of blood where he’d fallen. But his body was gone. I crossed to the gutter where his head had been tossed like garbage and grimaced as if I were already looking at it in the muck and refuse. But it was not there. Someone, something, had taken my husband’s decapitated body and his head, his remains . Someone had taken first my children and now the remains of my murdered husband.

I stumbled back to the car, and as I got inside, looked up and saw that the gate was swung wide open, and standing behind it in the driveway was Sam Clement. He waved me forward, and I drove the car in from the street. As I stepped from the car, Sam clanked the gate shut again and locked it.

“You left the key in the lock,” he said. “Not a good idea. It’s lucky I came by before anyone else did, or you wouldn’t have much to come home to.”

My entire body was shaking, and I started to cry. Sam put his arms around me and held me until I could finally speak. “Woodrow … he’s dead, Sam. They killed him. And the boys, my sons, they’re gone. I don’t know where they are! I’ve been driving around all night trying to find them. Can you help me, Sam? I don’t know what to do anymore.”

“C’mon inside,” he said in a low voice. “I know about… Woodrow. I saw his body when I got here.”

“His body! They cut off his head, Sam. It was Satterthwaite, him and three other men. They weren’t soldiers, but I know Doe sent them.”

“Probably, yes. He’s gone all paranoid and wiggy and is sending out all kinds of headhunters. They’re doing their dirty work all over the city. C’mon, I’ll get you a drink. I found some candles inside and Woodrow’s whiskey. Hope you don’t mind,” he added as we crossed the terrace and went inside.

“But the boys, Sam? Doe wouldn’t take my sons, would he?”

“Can’t imagine he’d bother,” he said and in the flickering candlelight stepped quickly to the liquor cabinet and half filled a glass with scotch. “Besides, they’re Americans.”

“What?”

“Well, half and half.” He handed me the drink, took up his own, and sat in Woodrow’s easy chair.

I fell back into the chair opposite, suddenly exhausted. The whiskey burned my throat, but it calmed my shaking limbs and brought my thoughts more or less back into focus. I realized that I hadn’t heard or seen the dogs. “Where are the dogs?”

Sam exhaled heavily. “Yes, well, the dogs. When I got here, with Woodrow’s body out in the street and the car gone and the house dark and silent, I was afraid something equally bad had happened to you and the boys. I had to get inside. I unlocked the gate easily enough, due to your leaving the key in it, but the dogs wouldn’t let me pass. I’m sorry, Hannah. I had to shoot them. There was no other way to get inside the house.”

“Oh, God, you shot our dogs?” I put down my glass. “Sam, you carry a gun?”

“I do.” He touched the breast pocket of his suit jacket.

“Christ,” I said. After a few seconds of silence, I asked him again about the boys. “I’m terrified. They’re my babies, Sam.” I started to cry again. “Damn it, I hate my fucking crying!” I yelled, and stopped immediately.

Sam asked if the boys had seen Woodrow killed.

“Yes. They watched from the car. Satterthwaite and three others pulled him out of the car and made him get down on his hands and knees. And then one of them cut off Woodrow’s head, Sam. It was … awful. He did it with a machete. And the boys … they watched it happen.”

He stood and refilled his glass at the bar. With his back to me, he asked, “Did they know it was Doe who had Woodrow killed?”

“Dillon, I think Dillon knew. Woodrow came home afraid and crazed and insisted on driving to Fuama with the boys tonight. He said Doe had turned on him. I’m sure that registered with Dillon and very likely with the twins, too. They’re fourteen and thirteen, Sam. They don’t miss much.”

“So they know,” he said, still with his back to me.

“Yes.”

He turned and sat back down in Woodrow’s chair. “That’s too bad, then.”

“Why? I don’t understand.”

“Yes, you do,” he said quietly. “You just don’t want to admit it to yourself. You probably knew it the second you realized they were gone.”

For a long moment neither of us said anything. Distant gunfire rattled the windows. Otherwise, silence. Finally, I said, “You’re right. I’ve been driving all over the city tonight as if I were looking for my sons. But I knew the whole time I wouldn’t find them.”

“So you understand that by now they’re either with one of Prince Johnson’s outfits on the other side of the river or else with one of Charles Taylor’s.”

“Yes.”

“More likely Prince Johnson’s. Charles’s people are still pretty much locked down at Robertsfield for the time being. Johnson’s just over the bridge.”

I nodded. I understood what was happening, I was living inside it; it was my life, but I couldn’t quite believe that it was real. I asked Sam if he had moved Woodrow’s body.

“Yes. I dug a shallow grave out there in back of the house. It’s in the flower garden. When this is over, you can put together a proper funeral for him. I’ll show you later where I buried him.”

“You found … the head, too?”

“Yes, I’m afraid so.”

“Thank you.”

“You’re welcome.”

“Sam, what am I going to do? What can I do?”

He took a swallow from his drink. “Only one thing you can do now.”

“What?”

“Get the hell out of Africa.”

BUT I DIDN’T LEAVE. For a while I was able to continue searching for my sons and caring for my dreamers. There was murder and mayhem all around me during those weeks, but strangely very little of it touched me directly. At least at the time it seemed strange. Later, I understood.

Every morning I drove through the nearly deserted streets of Monrovia, passing bodies, many of them mutilated and half devoured by dogs and other scavengers during the night, with smoke rising from the outskirts where fighting continued between Doe’s dwindling forces and Prince Johnson’s bands of men and boys in the eastern suburbs. Charles Taylor’s forces were approaching from the south. Rumors of Doe’s imminent collapse and surrender floated through the city like errant breezes. There were hourly radio broadcasts and declarations of victory by all three parties to the war, each of them in turn denying the claims of the other two, until it became impossible to gauge the direction or flow of the conflict. Because I seemed to be immune to its effects, of so little value or threat to any of the warring parties that I was able to pass through the checkpoints more or less at will, I was able to ignore the daily advances and retreats and dealt with the war as if its outcome would have nothing to do with me or my sons or my dreamers. I was too numb with fear and grief, too horrified and shocked by the killing of Woodrow and my sons’ disappearance, to worry about the larger effects of the war.

And so I moved more or less freely throughout the city, while the war raged around me. There were checkpoints all over now, run by boys not much older than Dillon, heavily armed and wearing looted clothing and gear, bizarre combinations of women’s clothes, formal wear, and shirts and shorts plastered with the logos of American sports teams. They wore juju amulets that were supposed to make the boys bulletproof and heavy gold chains and medallions that made them look like deracinated rap singers. Regardless of the time of day or night, they were high on drugs and raw alcohol, their minds deranged by what they had seen and done in the war. At every stop they demanded money from me, and as soon as I gave them a few dollars, they let me pass. Every time I saw a new group of boys coming towards my car with their guns cocked and their hands already out for money, I asked them if they knew the whereabouts of the sons of Woodrow Sundiata, and usually they cackled and laughed at my question, as if I’d asked if they knew the whereabouts of Michael Jackson, or they ignored my question altogether, took my money, and waved for me to go on.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Darling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Darling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Darling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.