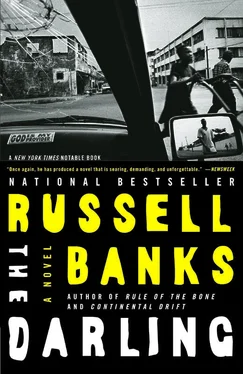

Russell Banks - The Darling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Darling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Darling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Darling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Darling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of Hannah Musgrave, a political radical and member of the Weather Underground.

Hannah flees America for West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends of the notorious warlord and ex-president, Charles Taylor. Hannah's encounter with Taylor ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah's family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

The Darling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Darling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the mornings before leaving for school, Bettina sat silently at the table and ate her Cheerios, while I, also silent, braided her long, pale hair into pigtails like mine, and Carol slept in. At night, before Bettina went to bed, I brushed her hair out again. Grooming. Before long, my days and nights were organized around Bettina’s, which helped me avoid thinking about what I was doing living here with this child and her mother and what I would do when my money ran out. It helped me avoid thinking about Liberia and Charles’s promise to give the country back to its people and what that might mean to Woodrow and our sons and to me, which meant that I didn’t have to ask myself if the promise Charles had made to me was as empty as the promise he’d made to poor, gullible Zack. And it helped me avoid thinking about the children I had left behind in Monrovia, my three African sons and their father, and the life I had, after a fashion, led there. Then one Friday late in September, Carol borrowed my car — my mother’s car — and she and Bettina and Carol’s mother drove to the White Mountains of New Hampshire to view the technicolor fall foliage, an annual rite for them, apparently, but for me little more than an occasion for making intelligence-deprived declarations about the beauty of nature. Not my cup of tea. I declined the invitation to join them, and for the first time since my return to America was alone for two whole days and nights. In the gray silence of the empty apartment — once I had vacuumed and dusted every room, finished the laundry, mopped the kitchen floors, and scrubbed the refrigerator down, once I was unable to come up with anything else to do that was in the slightest way necessary or merely useful to me or anyone else — my thoughts turned helplessly to my home in Monrovia. I sat down at the kitchen table with Bettina’s school tablet in front of me, opened it, and began a letter to my husband.

Dear Woodrow,

It feels strange to be writing to you like this, as if we’re on different planets. In spite of everything, however, you are still my husband and I’m still the mother of our three sons. Yet from this distance and for a variety of reasons which I’ll not trouble you with, I feel like an unnatural wife and mother and have no idea of how you and the boys feel towards me. Do you hate me? Are you glad that I am so far from you? I sometimes think that my absence has freed you to live a more natural life, a normal life, something that my presence made nearly impossible for you.

I wondered if now I was living a more natural life, too, if this was my normal life, or if I even had one. What were other women like me, my social peers and contemporaries, doing now? I wondered. They were white, American baby boomers born to privilege and trained to sustain that privilege and pass it on to their children. They’d had their taste of political activism in the sixties, “experimented” with drugs and sex, and after a year or two of graduate school had chosen mates with the same degree of ease and confidence with which, thanks to the women’s liberation movement, they’d slid into professions. By now they’d had two-point-three babies, at least one short-lived love affair, and seen a shrink once a week for a year or two to deal with guilt, marital strife, and early-onset depression generated by the failure of the women’s liberation movement to make them feel liberated. Most of them had resolved the conflict between child-rearing and career by temporarily shelving the career, and half of them had gone through a divorce, or would as soon as the children became teenagers and went off to boarding school. They were worried about their weight and their husbands’ eye for younger women. They were becoming their mothers. But what about me? What had I done all those years? Who was I becoming?

I don’t want to burden you with my feelings. They haven’t been of much use or interest to you in the past and are probably even less so now. I’m writing so that you and the boys (if you choose to relay this information to them) will know where I am and that I still love you. Though it has been very painful for me to have been exiled like this, I do not blame you for it. I know that you (and I) had no choice in the matter. I also know that someday this separation will be over and we will be together as a family again. Perhaps you have worried about me since I left Monrovia three months ago. Perhaps you haven’t. I have no way of knowing. Surely the boys have wondered how and where I was? I think of them all the time, especially at night when I am alone, and I can hardly keep from crying. I’m living with an old friend who has taken me in and I’ll soon be working as a volunteer at the school that my friend’s daughter attends. I’ll be the school librarian and will be with children all day long. My friend’s daughter is a lovely child and we’ve grown close, but it only makes me miss my own children all the more. Please tell me how they are faring without me. Naturally I hope that they are doing so well and are so happy that they barely notice my absence. At the same time I want to think that they miss me as much as I miss them.

It wasn’t true that I could hardly keep from crying at night. Nights, after I put Bettina to bed, I sat up reading paperbacks of nineteenth-century English novels — Dickens, mostly — waiting for Carol to come home from work. She got back to the apartment shortly before ten, and on Fridays and weekends came in around midnight. Our routine varied little. We’d smoke a joint together, watch a half-hour of television, and go to bed, and once a week or so, seduced more by the pot than each other’s bodies, we’d make slow, languorous love to one another. It was more a form of mutual masturbation than actual love-making, and afterwards I slept deeply and without dreams.

There is some sad news — sad to me, at least. Within days of my return to the States, my father passed away. I know you always thought of me as something of an orphan, a woman without a family, but I’m not. I loved my father very much, although from afar, and always hoped that you and the boys and my parents would come to know one another. Now that’s impossible — at least with regard to my father. Perhaps someday you will know my mother, however, even though I myself find her very difficult to be with, for reasons I’m sure you would never understand or respect. But that’s all right. I’ve grown used to the deep differences between you and me and accept them and do not mind them. I hope you can feel the same way.

A week earlier, I’d suddenly found myself worrying about my mother’s health and telephoned her in Emerson. Relieved when she didn’t pick up, I left a message on her answering machine “It’s Hannah. I’m staying with friends. If you need to reach me in an emergency, call The Pequod Restaurant in New Bedford and ask for Carol. She’ll know how to reach me. But call only if it’s an emergency. And don’t worry about your car. I’ll return it as soon as I have one of my own. ’Bye.”

That night I said to Carol, “If anyone ever calls you at work and wants to send a message to someone named Hannah, it’s okay. That’s me.”

“Who is?”

“Hannah. It’s not really me. It’s what my mother calls me.”

“Don, that’s weird.”

“It’s just a family nickname.”

“No, weird that you never talk about her.”

“Who?”

“Your mother.”

“I know.”

“That’s weird, Don.”

“I know.”

You can write to me (if you wish to) at this address as I expect to be here until I’m able to return to Monrovia without endangering you or the boys in any way. From this distance it’s hard for me to believe that you are in danger, yet I know it’s true. There is no news here of Liberia, and I have no Liberian contacts except through the embassy in Washington and the consulate in New York, and I’m afraid to get in touch with anyone there, for reasons I’m sure you understand all too well. I don’t know how private this letter is, so there are certain personal matters I won’t go into here, for obvious reasons. We are still husband and wife, after all, and I still have many wifely thoughts that are meant for your eyes and ears only. You were never much for writing letters, unless on official ministry business, but I do hope you’ll write back to me and tell me as much as you can of your and the boys’ circumstances. I’ll understand if you have to be circumspect. These days one can’t be too careful. But surely the boys can write to me? And I to them? We haven’t been forbidden that, have we? Well, I’ll know the answer to that if this letter goes unanswered by you and I do not hear from my sons. I don’t know if I could bear that, Woodrow. But I don’t know what I can do about it. My life as a wife and mother is not in my hands anymore. Perhaps yours, as a husband, is not in your hands anymore either. I don’t mean to sound overly dramatic, but I need you to tell me what I am to do with my life. I have very few options, and they are somewhat extreme. What I want is to come home to Monrovia (yes, it is my home, I have no other). I want to come home to my husband and my three sons.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Darling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Darling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Darling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.