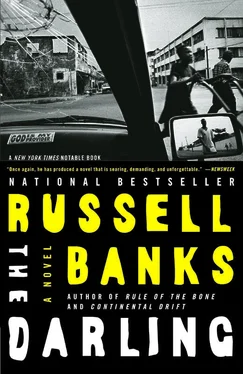

Russell Banks - The Darling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Darling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Darling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Darling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Darling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of Hannah Musgrave, a political radical and member of the Weather Underground.

Hannah flees America for West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends of the notorious warlord and ex-president, Charles Taylor. Hannah's encounter with Taylor ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah's family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

The Darling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Darling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

All at once I seemed to be living a wholly different life from the one I’d been living barely an hour ago, with different rules, different intentions, and utterly different strategies for survival. I flopped down on the sofa, exhausted. What should I do? What could I do? I glanced at the telephone squatting on the table beside me and instantly decided to call Charles Taylor. It wasn’t exactly the next logical step, but I had no idea what was. Maybe Charles would say something that indirectly indicated where I should turn next; or maybe he would even tell me outright what I should do to save my husband. He surely was still Woodrow’s friend. My friend, too. Whatever he was doing tonight, it was against his will. He was acting on the leader’s orders, that’s all.

A quick search of Woodrow’s rolltop desk in the cubicle off the living room, and I had Charles’s home number. After a dozen rings, a woman picked up.

“Mist’ Taylor, him na home,” the woman whined, as if wakened from a deep sleep. One of Charles’s harem girls, I supposed.

“Fine, fine,” I said. “Ask him to call Mrs. Sundiata as soon as he returns. No matter how late,” I added, although I knew at once Charles would likely not get the message and, even if he did, would not call, not yet. I shouldn’t have called him. A mysterious and scary business was unfolding, and Charles was no mere messenger boy for the leader. There was more to come, surely. He owed me nothing anyhow. He was possibly in danger himself, and my call might have made things worse for him. At that time, I rather liked Charles Taylor. Of all Woodrow’s friends and colleagues, he was the most worldly and congenial, and in his relations with me he was downright charming. A ladies’ man, I’d decided, even before I learned of his harem, a claque of teenage girls and very young women, most of them from the backcountry, beautiful, interchangeable parts in Charles’s domestic life and rarely appearing with him outside his compound and never at a government function. I’d seen them mainly at his home, when visiting with Woodrow for drinks and dinner. They were gorgeously plumed birds kept in cages, nameless, for Charles never bothered to introduce them to me. One doesn’t introduce one’s servants to one’s dinner guests. Actually, they were more like groupies than servants. Charles had a rock star’s charisma and presence and generated a sexual force field that made him glow and allowed him to treat those who warmed themselves at his fire with benign neglect.

I’m not sure how benign it really was, though. Each time Woodrow and I visited Charles’s compound out on Caret Street, the girls I’d seen there previously had been replaced by new, younger girls, and I wondered what happened to the caged birds they’d replaced. Set free, flown back to the country? Not likely. More likely they’d become prostitutes, and were possibly now among those who entertained Woodrow and Charles and their friends and colleagues on those increasingly frequent nights when Woodrow didn’t come home from the ministry until dawn. I knew, of course, what went on. A wife always knows, and besides, this was Liberia, not Westchester County. After a while, when new birds appeared and boredom with the old ones set in, Charles probably just recycled the girls by passing them down the chain of command — first to the Assistant Minister of General Services, then to the Administrative Officer for the Ministry of General Services, on to the Director of the Office of Temporary Employment of General Services, all the way to the lowest clerk in the ministry, who could not afford to house or feed anyone but himself and family, and so the girl would turn to the soldiers or hit the streets, which amounted to the same thing.

All night long, I waited to hear from my husband — a phone call or, more likely, as I persisted in thinking, his actual return, angry and humiliated by his treatment at the hands of the leader and his one-time friend, Charles Taylor. You may prefer not to know this about me, but secretly, deep in the dark chambers of my many-chambered heart, Woodrow’s arrest pleased me. It wasn’t very wifely of me, I know, and it certainly was not in my best interests or my sons’, for we were as dependent on Woodrow as his niece Jeannine was. The entire household, even the chimps, were dependent on the man. He had insisted on it. It was, especially for Woodrow, the only way to live together, it was the African way, and all of us, Jeannine and Kuyo and I, had happily complied.

I sat there on the couch and considered my situation and how helpless I had suddenly become. I remembered my vows as a teenage girl and later as a grown woman never, never to become dependent on a man’s fate. I’d seen early on how it had paralyzed my mother, and from that vantage point, still a girl’s, I had looked ahead at what the world would offer me when I became a woman, and had pledged that I would take it only on my own terms. I would gladly accept from a man responsibility, commitment, recompense, and reward, but only if they were reciprocal and I were free to walk away from the man when and if he broke the contract or became a danger to me. The years in the Movement from college on had only reinforced this pledge, educating me as to its inextricable link to my personal freedom. I fought with my male classmates at Brandeis, who called me a bitch, a dyke, a cock-teasing, ball-busting feminist; and I argued with and sternly critiqued my male comrades in SDS and Weather, the boys who called themselves men and the women girls and said they really appreciated my contribution to the discussion, but let’s go back to my room and fuck and then you can make breakfast for me in the morning . Later, underground, I demanded of my cellmates total upfront clarity and agreement on splitting equally all financial, household, and childcare responsibilities and labor, even when the child was not mine and neither of the parents my lover.

Lord, all those vows, all those promises and contracts — broken, abandoned, nearly forgotten! Throughout the night, I lay in bed waiting for Woodrow’s return, for, all evidence to the contrary, I still believed that this was, at worst, another of the leader’s ways of intimidating and keeping loyal one of the most loyal members of his government. The other members of his government, more dangerous than Woodrow, had long since been disposed of. It was a move typical of Samuel Doe. He was famous for it. Arrest the man for a night, and send his best friend and fellow minister to do the job. It’ll keep the both of them in line.

While I waited, tossing restlessly beneath the gauzy mosquito netting, I let myself play out little scenarios, dimly lit fantasies that up to now I’d kept pretty much hidden from myself, like a secret stash of pornography tucked in the dark back corner of a closet. I saw myself settled in a small house, like the old Firestone cottage I’d lived in when I first arrived in Liberia, only with an extra bedroom for the boys to share, and located a few miles inland from Monrovia. The four of us would take care of the chimps, my dreamers. That’s all, a simple life. I’d school the boys at home, and I’d read to them at night, and they’d play with the children of the village, while I socialized with the other mothers, went to market with them, and cooked native food the native way on my own. A very simple life. Just me and the boys and the dreamers and the villagers and the jungle.

And when I grew tired of that fantasy, or it grew too complicated and was no longer sustainable, I envisioned a life here in town, a continuation of my present life, except that now Woodrow was no longer a part of my life, and I was free to be the white American woman with three brown sons living in the big white house on Duport Road with the view of the bay, the woman who ran the sanctuary for the chimpanzees, the woman with the mysterious past who could never return to her native land, who was occasionally seen at one of the better restaurants in town on the arm of an official from one of the European embassies, was sometimes mentioned in the society column of the Post as one of the guests at an embassy party. Or even, why not, seen dancing at a Masonic ball with Minister Charles Taylor. Which would indeed complicate things, no?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Darling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Darling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Darling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.