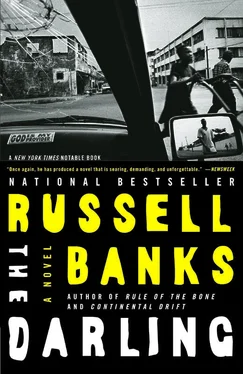

Russell Banks - The Darling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Darling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Darling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Darling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Darling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of Hannah Musgrave, a political radical and member of the Weather Underground.

Hannah flees America for West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends of the notorious warlord and ex-president, Charles Taylor. Hannah's encounter with Taylor ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah's family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

The Darling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Darling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When I look back now, so many years later, an old lady sitting on her porch here in Keene Valley or sipping her beer at the Ausable Inn or out on the lawn in the shade of a maple tree, telling my story to a friend and remembering the world I lived in then, I know what I could and should have been doing with my time and riches and my abundant privileges. I was surrounded daily, after all, by abject poverty so pervasive and deeply embedded that, though I could never have alleviated it in the slightest, I could have altered significantly the lives of at least a few individuals, people to whom I was related by marriage, for instance, and people who worked for us, and even neighbors, for, although we lived in one of the poshest neighborhoods of Monrovia, there were huts and tiny, sweltering, tin-roofed cabins tucked into the warren of back alleys nearby that housed whole families just barely scraping by and always on the verge of starvation. But even within that small circle of desperately needy family members, friends, and neighbors, I provided no meaningful, lasting help. Whether the poverty inside that circle was truly unalterable, like that of the rest of the country, I couldn’t say even today, but it seemed to me then a fixed and hopelessly unfixable condition, as permanent and unalterable as a gene code.

Beyond that small circle, of course, poverty was indeed fixed. If I bothered to walk ten blocks beyond our Duport Road enclave, I’d find myself in the middle of a workers’ quarter jammed with mostly illiterate young men from the country, tens of thousands of them with only a farm boy’s skills who had drifted into the city to find work, and finding none, had stayed to see their lives die on the vine, unplucked. They became thieves, pickpockets, extortionists, and beggars. They became drunks and drug addicts. Or they joined the army solely for the shelter and clothing it promised, and because they almost never got paid, they continued to steal, extort, and beg, only now with a gun in their hands. Joining them, plying their trade on these narrow streets at night, were loosely organized troops of prostitutes, most of them girls from the country following the boys, or girls kicked out of their villages by their husbands for having gotten pregnant in adultery or by their parents for having gotten pregnant out of wedlock. There were the so-called rope hotels, muddy, room-size squares of ground surrounded by a head-high cinder-block wall with a thatched roof on poles. Inside the walls, at the height of an adult’s armpit, ropes were strung like clothesline across the enclosed space. For a dime, a homeless man or woman could drape his or her weight over the rope like a blanket and sleep all night, dry and more or less safe from the dangerous streets and alleys. Babies, naked and crusted with fly-spotted sores played listlessly in puddles of sewage. Vast midden heaps at the edge of the city were ringed by settlements of huts made from refrigerator cartons, the rusted carcasses of wrecked cars, cast-off doors and broken crates — whole villages of human scavengers sifting the towering, constantly expanding piles for scraps of cloth or paper that could be used or sold, kids and old women fighting with the rats and packs of wild dogs for bits of tossed-out food. It all seemed so hopeless to me that I averted my gaze. I did not want to see what I could not begin to change.

Yet at any time, once my babies were born, I could have put my shoulder to the wheel of one or several of the dozens of volunteer and non-governmental charitable organizations that were stuck to their hubs in the mud of Liberian corruption, cynicism, and sloth. I could have distributed condoms, medical supplies, food, clean water, information. It was eight years between my marriage to Woodrow and my first return to America (an event I’ll tell you about very soon), and in those years I could have taught a hundred adults to read. I could have bribed a hundred parents to keep their daughters from working in the fields or on the streets and paid for the girls’ secondary-school education. I could have been a one-woman Peace Corps with no nationalist agenda, a one-woman charity with no religious program, a one-woman relief agency with no bureaucracy or salaried administrators to answer to. It wouldn’t have changed the world or human nature, and probably wouldn’t have altered a single sentence in the history of Liberia. But it would have changed me. And, a different person, I might have avoided some of the harm I inflicted later both on myself and others.

Instead, I gave out tips and Christmas bonuses and little presents on Boxing Day, a holiday that Liberians, not letting a good thing pass unappropriated, had borrowed from Sierra Leone. I dropped dimes and quarters into the cups of crippled and deformed, leprous, and amputated beggars on the streets of Monrovia, gave pennies to children who clustered around me whenever I stepped from the Mercedes, and although I myself did not attend services (a girl has to have some principles, I suppose), I supported Woodrow’s church by sending our children to its Sunday school with dollar bills for the collection plate tucked into pledge envelopes.

It was as if the people who lived there and the events that took place in those tumultuous years were deadly viruses, and I lived behind glass, a bubble-girl protected against infection from the outside world. Meanwhile, beyond my bubble the president and his cohort, which, despite my husband’s best efforts and advantageous marriage, still did not include him, grew fatter and richer and ever more flagrantly corrupt. They skimmed the cream off American foreign aid, blatantly stole from any and all non-governmental and UN public service allocations, took their cut from World Bank and IMF grants to the financial sector, and pimped the country’s natural resources, selling off at special, one-day-only rates Liberia’s rubber, sugar, rice, diamonds, iron, and water, peddling vast stands of mahogany and timber to companies owned and run by Swedes, Americans, Brits, Germans, and, increasingly, Israelis. Foreign distributors of beer, gasoline, motor vehicles, cigarettes, salt, electricity, and telephone service haggled over lunch for bargain-priced monopolies; by sundown they had the president’s fee safely deposited in his Swiss bank account and, after the celebratory banquet, partied the night away at the Executive Mansion with Russian hookers, smoking Syrian hashish, snorting lines of Afghan cocaine, and guzzling cases of Courvoisier.

The few Liberian journalists and politicians who dared to criticize the president and his cronies simply disappeared. As if sent on permanent assignment to Nigeria or Côte d’Ivoire, they were not mentioned again in public or private. Newspapers were locked down by judicial fiat, and radio stations were silenced, until the only news, little more than recycled releases from the president’s press office, was no news at all. Meanwhile, the president’s personal security force grew larger in number and actual physical size — big, scowling, swaggering men in sunglasses looking more and more like an army of private body guards than an elite corps of enlisted men — while the men in the regular army seemed to diminish in number and size, their uniforms tattered, torn, and dirty, their boots replaced by broken-backed sneakers and plastic sandals. Compared with the glistening black AK-47s carried by the president’s men, their rifles, obsolete U.S. Army leftovers from the Korean War, looked almost antique and were without ammunition. More like dangerous toys than deadly weapons, they were used mainly as clubs.

I knew all this as it happened, saw it with my own eyes, and learned the details and background and the names and motives of the people involved from Woodrow, from the few of his colleagues in government who, like Charles Taylor, trusted him, and from our social acquaintances — and, of course, I learned of it from Jeannine, who loved showing me that she knew more about the world of Liberian big men and their affairs than I did, and from Elizabeth, who had taken over my old job at the lab and whom I visited daily to be with the chimps. For, when it came down to it, the chimps had become my closest friends in Liberia, my only confidants, the only creatures to whom I entrusted my secrets, and whose secrets I kept and carried.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Darling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Darling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Darling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.