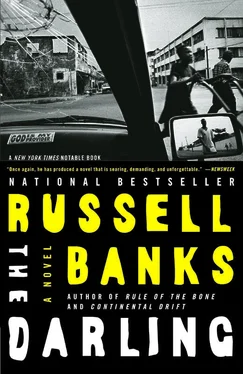

Russell Banks - The Darling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Darling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Darling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Darling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Darling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of Hannah Musgrave, a political radical and member of the Weather Underground.

Hannah flees America for West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends of the notorious warlord and ex-president, Charles Taylor. Hannah's encounter with Taylor ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah's family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

The Darling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Darling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When I was a little girl, from as early as I can remember, we had a dog who loved me the same way I loved her, a white female Samoyed named Maya. Her name suggested Daddy’s taste, surely, not Mother’s, but I didn’t think of it that way then: Maya’s name came with her, and she embodied it, just as I did mine. I had no invisible friend to keep me company, and never wished for a brother or sister. I had Maya. Before all others, I loved Maya, and knew her, and she loved and knew me. We were authentically whole individuals to each other, unique and irreplaceable. Not that I thought she was human or that I was a dog — our species difference mattered less than if we’d had different genders. We played and studied together, slept together, even talked to one another in a language that only we two understood. But Maya grew old faster than I did, and when I was eleven and she was eleven, she developed arthritis and took to snoozing in the shade under Daddy’s car. Her habit was to lie under the rear bumper after she’d gone outside in the morning and had finished her business, as if the effort of peeing in the side yard necessitated a short period of private rest and reflection afterwards. This was before I went away to Rosemary Hall, and every morning, when he was not traveling, Daddy drove me to school at Huntington Chase. His habit was to start the car and run the engine for a minute before backing it out of the driveway, to give Maya time to crawl from beneath the car. But then, inevitably, there came the day, a blustery, unseasonably warm, spring-like February morning, when Daddy turned on the ignition, waited the usual ninety seconds before putting the car into reverse, and as soon as the car began to move, we heard and felt a bump underneath, and he and I knew instantly that he had run over Maya and killed her. I had just begun to insist on being called Scout then, and Scout didn’t cry when her dog was killed by her father. Without looking up from the open schoolbook in her lap, Scout said simply, “You ran over Maya.” I remember Daddy practically leaping from the car and lifting Maya in his arms. He held her as if she were a full-length fur coat and stood by the open car door, looking back at me with a strangely puzzled expression on his face, as if he couldn’t quite believe what he had done. “I’m so sorry, dear,” he said. I didn’t respond. In my rapidly hardening heart I knew that he’d grown weary of her inconvenience and the demands that her old age put on us and for an instant had willfully blocked out the fact of her existence. I had no word for it yet, but I believed in the unconscious and knew that it was very powerful, especially when it came to adult behavior. He said, “I think she was already dead, though. She was very old. Old and weak. I think she must have died before we came out. Or she’d have moved from under the car the way she always does. We’ll bury her in the backyard, okay? We’ll stay home this morning, you from school and me from the office, and we’ll bury her by the pear tree. How does that sound, Hannah?” “Scout,” I said and went back to my book. “Scout,” he repeated, his voice dropping to a whisper. Mother suddenly appeared at the door behind him. “What happened to Maya?” she asked. Daddy turned and showed her, and she said, “Oh, my! Are you all right, Hannah dear?” “Scout,” I corrected. “I’m fine,” I said and looked up at her. “It’s Maya who’s dead.” “Yes, of course. Yes. Poor Maya,” she said. I turned back to my book and pretended to read, while my parents stood there by the car, my father with the dog in his arms, my mother wringing her hands uselessly, the two of them staring in hurt confusion at their cold child. Without looking at them, I said, “It’s not like Maya’s a person, you know. A human being. And we don’t have to bury her by the pear tree. We can take her to the vet’s, and they can do whatever people do with dogs that die of old age.” And then I told my father to hurry up and drive me to school or I’d be late.

Dear Hannah, how I would love to be able to hug you and sit face to face with you and talk the night through. I wonder if it’s possible for us to visit you there. I understand, of course, that you can’t visit us here, but maybe we could fly over to Africa and be with you for a few days. It would mean so much to us if we could all be together again, however briefly. I would love to see where you work, meet your friends (especially this mysterious new man-friend you mentioned), and travel about the countryside some and “see the sights.” Neither your father nor I have been to Africa before, you know, although your father keeps saying he wants to go to South Africa and support the anti-apartheid movement in some fashion that’s appropriate to his profession and his public standing here in the U.S., probably by forming an international organization of physicians opposed to apartheid. It’s possible that we could come first to Liberia for a few days or a week and then fly on to South Africa. What would you think of that? Naturally, we wouldn’t want to inconvenience you in any way and would stay in a nearby hotel, rent a car, and so on, and would amuse ourselves quite capably while you were at work. We could hire a local guide and go sightseeing, then meet up with you afterwards. The very idea of it is exciting to me, and when I suggested it to your father, he was thrilled.

It amazed and disappointed me to see the ease with which my parents, simply by presenting themselves to me, could turn me into that cold child again. I read their letters and was transformed into Scout. Here I was, a woman in her middle-thirties who had accumulated a lifetime’s experiences that her parents would never even know about, let alone experience for themselves; yet, in their presence, even in as disembodied a form as an exchange of letters, my world shrank to the size and shape of theirs, as if I’d never left it.

I’ve gone on and on, especially for a letter that I’m not one hundred percent sure will even get to you, and so I really should close now. I love you, darling, and miss you terribly. Please write back soon.

All my love ,

Mother

I didn’t take the time to refold her letter and put it back into the envelope, before I was writing my answer. My hand trembled as the words scrawled across the page, and when I had finished, I did not bother to reread what I had written. I immediately sealed it, slapped on an airmail stamp — one of those famous Liberian chimpanzee stamps printed in small editions for foreign collectors — and headed straight for the little neighborhood post office, where, after a ten-minute wait for the postmistress to return from lunch, I handed it to her.

Dear Mother ,

The last thing I need is for you and Daddy to show up at my door! How can you even think of doing such a thing! I’m not a post-deb taking her Grand Tour in Africa and I’m not in the Peace Corps, thank you very much, Daddy. Please understand that my situation vis-à-vis the government of Liberia and the U.S. State Department is extremely delicate, and I’m more or less free to stay here solely by their leave. And I mean that, more or less free. And by their leave. The American authorities pretty much run the show in Liberia and they know who I am. I’m no longer underground, but as you surely must remember, Mother, there is still a federal warrant for my arrest that could be acted on any time they wish, for any reason they wish. Relations between the two countries are conducted not as between equals but rather on the basis of what’s in the best interests of the U.S. At the moment, because of an acute shortage here of medically trained personnel, it’s in the interests of the U.S. State Department and probably a few congressmen from New York and New Jersey to allow me, even with my low-level skills, to be employed basically as a lab assistant for an academic front financed by some huge, politically connected pharmaceutical company. The university is doing research that requires blood from chimpanzees, an animal that happens to be abundant in this region, research that, if successful, will some day produce the patent for an anti-hepatitis drug that will generate enormous profits for the pharmaceutical company sponsoring the research and in the end will make the shareholders of the company obscenely rich. Thus the complicity of the U.S. government and thus their interest in having me employed here. (I can’t believe I have to explain this to you!)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Darling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Darling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Darling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.