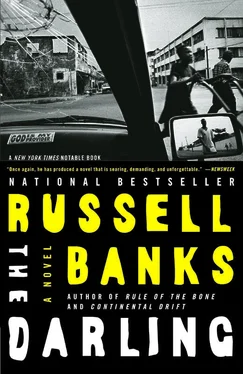

Russell Banks - The Darling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - The Darling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Darling

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Darling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Darling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is the story of Hannah Musgrave, a political radical and member of the Weather Underground.

Hannah flees America for West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends of the notorious warlord and ex-president, Charles Taylor. Hannah's encounter with Taylor ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah's family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

The Darling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Darling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

TEN DAYS LATER, I rode overland in the dark, traveling northwest from Côte d’Ivoire into Liberia and down to the coast from the Nimba highlands, most of the time hidden under a tarpaulin in the back of a truckload of milled boards. At first and for several hours, I rode up front beside the trucker. I had crossed the border illegally, but with no more difficulty than if I’d been a crate of Chinese rifles or a case of Johnny Walker whiskey. In West Africa, if you’re carrying enough U.S. cash, nearly any legal technicality can be erased. It had been a quick, hundred-dollar arrangement made with the driver of the truck, a slim, middle-aged Lebanese from Monrovia, a man with yellow eyes who licked his lips a lot and smiled like a lizard. His name was Mamoud. He owned the truck and was able to buy gas for it and bribe the guards at the borders — obviously an intelligent man thriving in evil times, and was dangerous therefore. I’d been passed on to Mamoud by the driver of the bush taxi I’d hired at the Abidjan airport to take me as far as Danane, a few kilometers east of the Liberian border. I hadn’t known it, but they were a team, the taxi driver and the trucker. Everyone in West Africa eventually turns out to be a member of a team.

At this particular crossing I was only smuggled goods, contraband, but at Robertsfield Airport in Monrovia or at one of the more carefully patrolled crossings, I’d have been a potential enemy of the state, stopped for certain and turned around and sent back to Côte d’Ivoire or possibly arrested and jailed. Which is why I had flown from JFK into Abidjan, on a Côte d’Ivoire tourist visa with no entry visa for Liberia. There had been no point in my even applying for one, and no reason to fly directly from Abidjan to Monrovia — quite the opposite, if I wanted to get into Liberia at all. Although the war was officially long over, the man who’d begun it, Charles Taylor — with whom I had once enjoyed a longtime personal relationship, let me say that much, and I will eventually tell you about that, too — was now president, elected by people who had voted for him to stop him from killing them. His enemies, the few who had come out of the war alive, had scattered into the jungles and across the borders into Sierra Leone or Guinea and had regrouped or, like me, had made their way to North America and Europe, where they plotted the death of the president and their own eventual return.

We had no problems at the border crossing, where Mamoud was evidently known and liked and must have had outstanding favors owed him. The soldiers simply waved him through, even with an unknown white woman sitting beside him. Mamoud’s French girlfren’, prob’ly. Dem Lebaneses got a taste for dem skinny ol’ white ladies . Laughter all around.

And then I was back in Liberia once again, passing darkened daub-and-wattle huts with conical thatched roofs and clusters of small cinder-block houses with roofs of corrugated tin and bare front porches and swept dirt yards and, alongside the road, a barefoot man or boy walking, suddenly splashed by the glare of the headlights, refusing to show his face or turn, just stepping off the road a foot or two, then disappearing into the blackness behind. Inside the roadside huts and houses I saw now and then a candle burning or the low, orange glow of a kerosene lantern, and here and there, close to the door, the red coals of a charcoal fire pit, and I caught for a second the smell of roasted meat and a glimpse of the ghostly figure of a woman tending the fire, her back to the road. It was all immediately familiar to me and comforting, and yet at the same time new and exotic, as if this were my first sight of the place and people and I had not lived here among them for many years. It was as if I had only read about them in novels and from that had vividly imagined them, and now they were actually before me, fitting that imagined template exactly, but with a sharpness and clarity that subtly altered everything and made it fresh and new.

It was the same anxious, edgy mingling of the known and unknown that greeted me when I made my first journey into the American South nearly forty years ago, when I was a college girl using her summer vacation to register black voters in Mississippi and Louisiana. I was an innocent, idealistic, Yankee girl whose vision of the South had arisen dripping with magnolia-scented decay and the thrill of racial violence from deep readings of William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor. A newly minted rebel, fresh faced and romantic, I rode the bus south that summer with hundreds like me into Mississippi, confident that we were about to cleanse our parents’ racist, oppressive world by means of idealism and simple hard work.

Up to that point, my most radical act had been to attend Brandeis instead of Smith, and I had done that solely to please my father and to avoid granting my mother’s unspoken wish that I follow her example. I’d never been out of New England, except for a high-school civics class trip to Washington, D.C., and a flight to Philadelphia for an admissions interview at Swarthmore, my second choice for college after Brandeis and my father’s first choice. But I had gazed overlong into those Southern novels and stories, and for many weeks that first summer in the South they provided the reflecting pool in which I saw where I was and the black and white people who lived there. Eventually, of course, literature got displaced by reality, as it invariably does, but for a while my everyday life had the clarity, intensity, and certitude of fiction.

A FEW MILES WEST of the town of Ganta, the road bends perilously close to the Guinea border, where, as I knew from the newspapers at home, there had been sporadic fighting in the last year between small bands of regular and irregular soldiers from the two neighboring countries — the usual jockeying for control of the Nimba diamond traffic. Even the New York Times seemed to know about that, which had surprised me. It was here, in the middle of a long stretch between rural villages, that Mamoud abruptly pulled over and parked the truck by the side of the road.

He told me to get out and bring my backpack, and I thought, Damn him! Damn the man. He knows who I am, or he’s just figured it out and he’s got evil on his mind . Back at the border, just as we crossed, he had insisted on learning my last name. When I said it, Sundiata, Woodrow’s well-known last name, he didn’t react. But I knew at once that I should have said only what it read on my passport, Musgrave, my father’s last name. Mamoud had merely smiled and then said nothing for the entire two hours after.

The old, all-too-familiar, Liberian paranoia came rushing over me. It’s in the air you breathe here. It’s like a virus. You can’t escape or defeat it. It hits you suddenly, like when you’ve had a close call. At first you feel foolish for not having been more frightened and warily suspicious, and you promise yourself that it won’t happen again, it had better not, because next time you may not be so lucky. From then on, you assume that everyone is lying, everyone wants to hurt you, to steal from you, and may even want to kill you.

I got slowly down from the truck, slung my pack onto my back, and made ready to bolt. On the near side the jungle came up tight to the road, but on the far side of the road I saw a field of high sawtooth grass and knew that if I got there before him, he’d have trouble catching me in the dark. I had no idea what I’d do after he gave up the chase and drove on. If he gave up and drove on. I was three hundred kilometers from the city of Monrovia, a white American woman afoot and alone. Never mind that there was probably a standing warrant for my arrest and the U.S. embassy would do nothing to protect me. All my chits with the Americans had been spent a decade ago. And never mind that there would probably be rumors of a reward offered by Charles Taylor personally, making me a target of opportunity for any Liberian with a knife or machete to slice my throat or take off my head. Liberia is a small country, and in any village, even out here in Nimba, my corpse could be exchanged for a boom box or maybe a motorbike and passed along in a farther exchange and then another, the price going up with each transaction, until finally what was left of my body, maybe just my head with its telltale hair, got dropped at the gate of the Executive Mansion in Monrovia.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Darling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Darling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Darling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.