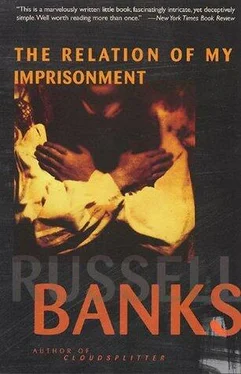

Russell Banks - Relation of My Imprisonment

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Banks - Relation of My Imprisonment» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Relation of My Imprisonment

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Relation of My Imprisonment: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Relation of My Imprisonment»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Relation of My Imprisonment — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Relation of My Imprisonment», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The reader should keep in mind that I did not at this time know what was yet to come, and therefore each new affliction I regarded as the last in a series. When I had developed boils, I did not know that favus would follow and that dry seborrhea would follow the favus. Nor did I know, when the dry seborrhea had cleared somewhat, that I would soon be afflicted by neuralgia, the chief symptom of which is extreme pain that comes on in paroxysms and severe twitching of the muscles of the affected part, in my case the cheeks of my face and the muscles surrounding my mouth. These symptoms took expression as a sudden grimace, practically an open-mouthed but silent laugh, despite the pain, and thus I was often thought to be enjoying some private hilarity, when in fact I was not. To further confuse people, one of the boils from my mouth had relocated in my right ear, to be followed by another in my left, and soon the swelling in the canals had become sufficiently extensive to cause a temporary but total deafness, so that I could not know what was being said to me and thus could not answer questions with regard to the incongruity between my facial expression and the absence of anything particularly humorous in my immediate situation or surroundings.

Along about this time I began to reason that there was a connection between my various afflictions, however tenuous, and I grew fearful, yet none of my diseases were such that they could be cured by any treatment other than rest and cleanliness, which were my habits to encourage anyhow. Unavoidably, one affliction seemed to lead to another, so that one night during my sleep, the neuralgic twitching of the muscles surrounding my mouth caused me to bite into the meat of my tongue accidentally, which in a short time became inflamed, swelling the tongue exceedingly and leading to an ulcerated and very tender condition and also several abcesses there. This condition brought on a constant and copious flow of saliva and also made it difficult and very painful to speak. In a few days I observed that my gums as well had become infected, for they had grown spongy and tender and had puffed out and sometimes bled and from time to time oozed pus from between my teeth. And still there was little I could do to cure myself, except to provide myself with rest and cleanliness.

Here I became sufficiently ill that the jailor at last brought a physician unto me, for there had appeared on the skin of my chest several large thickly encrusted areas of a purplish color. These masses of granulated tissue and tiny abcesses, bathed in a thin film of pus, had come from within my lungs, the physician thought, and indicated a condition he named blastomycosis, which he speculated had been caused by some type of yeast infection somewhere in my body. When I had told him of my dry seborrhea, he chuckled and said that it surely explained the cause but gave not a hint for the cure, for there was no cure, except to treat the affected areas of the skin with certain chemical solutions, which he dispensed to me and which I assiduously applied, bringing about a small measure of relief. I was left, however, with a painful cough and more or less difficulty with breathing, and with chills and sweats in alternation, and an indisputably foul-smelling sputum, these all coming as a result of the lung infection, which the physician told me might in time abate of its own volition.

I lay in my cot for most of my days now as well as the nights and no longer moved outside my cell. The pain from my lungs and from the boils and divers other sores as had appeared across my body and from the neuralgia and the diseases that filled my mouth and stopped up my ears, and the continuous itching in the various parts of my body, made me shrink inside myself like some dumb animal cowering in a corner, and I began to fear that I might be compelled, by my commitment to my life time’s period of penance, to live this way for a long time, and this brought me to conclude that my will to atone was being tested by the dead. I believed that the dead were trying me because there had come into my spirit during these weeks a longing to join them that was exceedingly strong and that was not altogether spiritual. Against this longing I brought forth numerous scriptures and remembered teachings from my youth and all my powers of reason, for this was now a clash that rang out continuously in my mind with all the noisesome fury of a great clash between armies. I know that I often wept and groaned aloud and thrashed helplessly through the long nights.

It was now that the physician began to attend to me daily, as if he did not expect me to live, and it was in that way that I learned of how the abcess in my lungs, when it had somewhat subsided, had created a certain amount of scar tissue adhering to the walls of the entry to my stomach, causing these walls to pull away and form a sac, which he called a diverticulum and which unavoidably, as the sac increased in size, filled with slivers of food. And when the particles of food decomposed there, the sac expanded still further until it had grown to the size of a tobacco pouch and had caused a foul odor and much pain and vomiting. As a joke, the physician told me that the best cure was starvation, for no matter how little I ate or what I ate, there was bound to be some small particle that would be drawn into this ever enlarging pouch. For several days thereafter I did indeed wrestle with the temptation to cure myself by starvation, but after a while I was able to overcome this test also and thus agreed to follow the physician’s instructions and attempted to keep food from entering the sac by laying myself in such a position as to place the sac at a level higher than the entry to my stomach, with the mouth of the sac pointed downward, which is to say, by lying on my right side with my head and shoulders on the floor and my hips and legs on the cot. Thus I was able to take a small amount of nourishment, mainly in the form of dry crumbly cereals so that the few grains which, despite these precautions, nevertheless got into the sac, could be drawn out daily by the physician with his rubber tube and pump.

But the cure for one affliction is frequently the cause of another, and because my diet was now restricted wholly to sips of water and bits of dry cereal, I soon developed the symptoms that accompany the absence of acid in the stomach, abdominal pain, headache, ringing in the ears, and constant drowsiness, a condition which additionally led quickly to pernicious anemia, which brought with it extreme weakness, breathlessness and heart palpitations. My skin all over my body, such of it as was not inflamed with boils and various sores, was a lemonish color, and my feet and hands had puffed out grotesquely. It now seemed to me that I would surely succumb to the temptation to die, for to live meant only to contract yet another, more nearly fatal disease whose cure seemed to be a still worse disease. When I slept, which was only in brief spasms, I had furious dreams, and though I wished for those among the dead to appear to me there and to advise me and I often cried out the name of my wife or of John Bethel or of my parents, none from the dead came to me then. Only the living appeared to me, in my sleep as much as when I was awake, my physician, my jailor, occasionally a curious prisoner who might have heard my groans, until I was no longer able to tell when I was not sleeping from when I was not awake, for in both states did these people appear to me in wildly threatening postures with their faces horribly distorted, as if they themselves had contracted all my diseases and had grown as grotesque to look upon as had I myself.

Now there came upon my body a great fever, which lasted for about ten days and nights and brought with it profuse night sweats and continuous headache, and when it had abated, left me weaker even than before, with certain of my other afflictions somewhat worsened, such as the neuralgic pains in my face and the coughing and the various symptoms of the pernicious anemia. The physician who had taken a sort of scientific interest in my case, for it presented him with many ongoing puzzles, could not at first diagnose this fever, until there had followed several more episodes of about ten days each, coming as if in waves, each one leaving me afterwards weaker than before. These waves, he said, were characteristic of undulant fever, an uncommon disease among the population as a whole but not uncommon among those who are known to deal with the dead, for it is contracted and spread chiefly by having come into contact with a similarly infected body or carcass, but because the germ often lies dormant for years, it is very difficult to trace the path of contagion. Thus, since my calling long ago had been as a coffin-maker, the physician had swiftly concluded that I doubtless at some time long before my imprisonment had dealt with an infected corpse, and it was only now, in my weakened condition, that the disease had made itself known to me. There was no cure for the disease that the physician knew of, but the symptoms could be treated as they appeared, and because he was interested in the course of the disease and in containing its spread, he determined to stay close to me and treat me as kindly as he could. He thought that he might thereby learn something about the disease so as to be able to devise preventive measures against its future occurrence, especially among the prison population.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Relation of My Imprisonment»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Relation of My Imprisonment» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Relation of My Imprisonment» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.