“This is when I ask why you want this information,” she said.

“Some unfinished business. Nothing for you to worry about.”

She squinted at me. “You know what Confucius said?”

“Remind me.”

“ ‘Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.’ ”

“I’ve always found ancient Chinese wisdom overrated.” I took out an envelope and handed it to her. It contained three thousand dollars in cash. She shoved it inside her bag, zipping it closed.

“How’s your German shepherd?” I asked.

“He died three months ago.”

“I’m sorry.”

She brushed her spiky bangs off her forehead, scrutinizing an elderly man who’d just boarded.

“All good things must come to an end,” she said. “We done here?”

I nodded. She looped the strap of her bag over her shoulder and was about to get up when I thought of something else and grabbed her wrist.

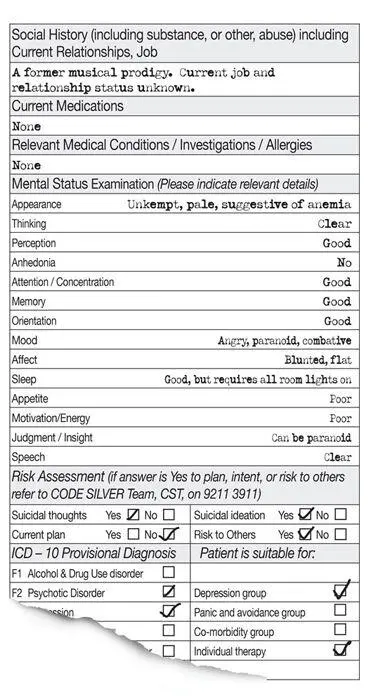

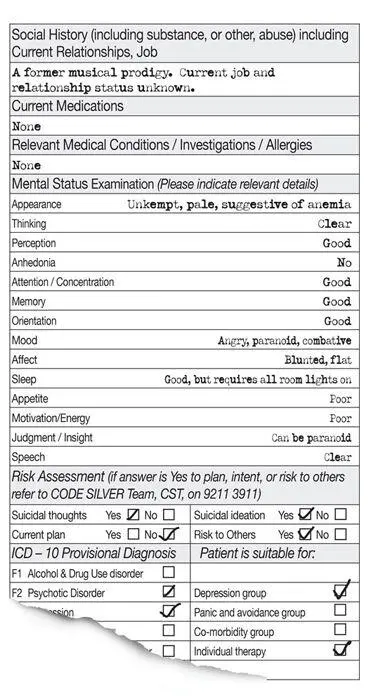

“What about a suicide note?” I asked.

“They didn’t find one.”

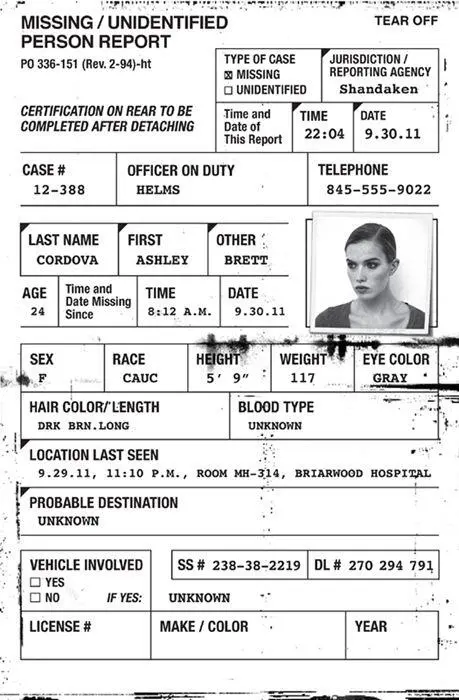

“Who identified Ashley at the morgue?”

“An attorney. The family hasn’t said a word. I hear they’re out of the country. Traveling. ”

With a look of regret but little surprise, she stood up, moving to the front of the bus. The driver instantly pulled over. Within seconds, she was scurrying down the sidewalk, though she didn’t walk so much as plow, shoulders hunched, eyes fixed on the ground. As the bus took off again with a belch, veering into the road, Sharon became just a shadowed figure moving past the closed stores and barred windows, swerving quickly around a corner — and she was gone.

“ Who is zis?”

The woman’s voice — thick, with a Russian accent — came out scratchy over the intercom.

“Scott McGrath,” I repeated, leaning toward the tiny black camera above the door buzzers. “I’m a friend of Wolfgang’s. He’s expecting me.”

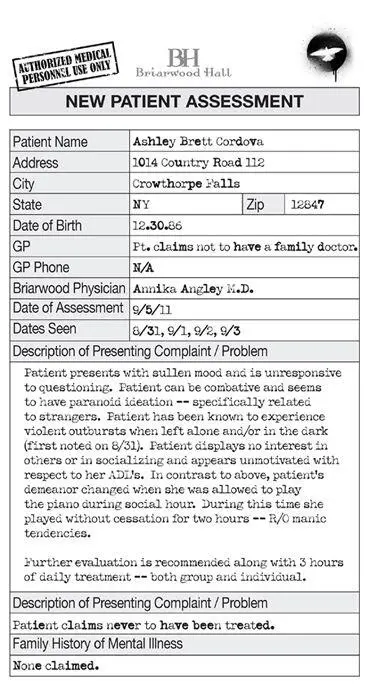

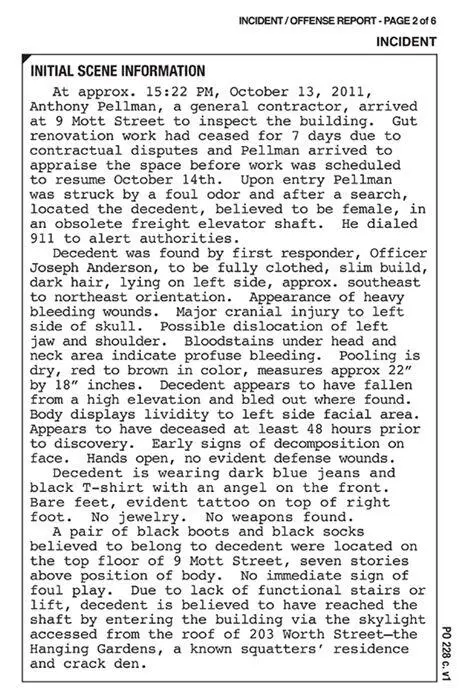

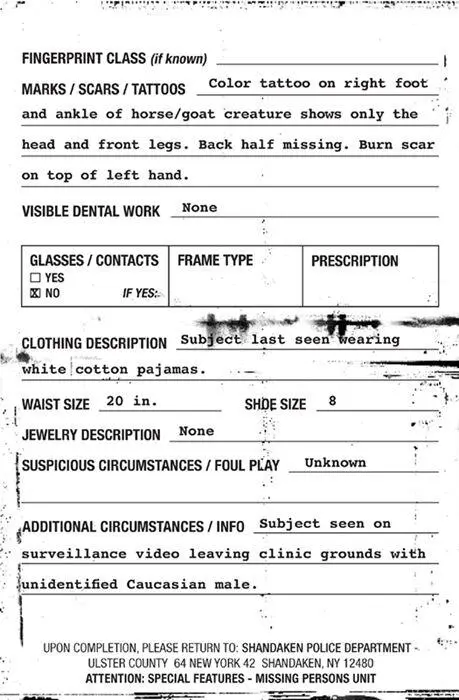

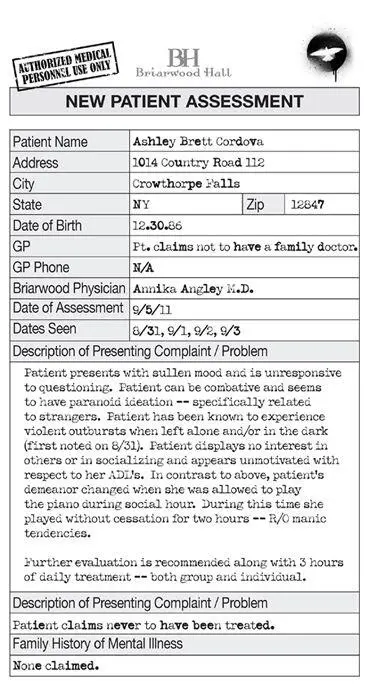

It was a lie. This morning, after reading through Ashley Cordova’s NYPD file, I’d spent the last three hours trying to track down Wolfgang Beckman: film scholar, professor, rabid Cordovite, and author of six books on cinema, including the popular tome on horror movies American Mask.

I’d tried his office in Columbia’s Dodge Hall, got his class schedule from the office, only to learn he was teaching just one class this semester, “Horror Topics in American Cinema,” Tuesday nights at seven. I’d called his office and cell but they clicked to voicemail, and given our last encounter more than a year ago — when he’d not only told me he hoped I rotted in hell, but had taken two wild, vodka-induced swings at me — I knew he’d sooner call back the pope. (There were two things Beckman truly loathed in life: sitting in the first three rows of a movie theater and the Catholic Church.) My last resort was to show up here, a run-down building on Riverside Drive and West Eighty-third, where I’d spent many an evening listening to him lecture in his mole burrow of an apartment, joined by his fleet of cats and a crowd of students who drank in his every word like kittens lapping up cream.

To my surprise, there was a scratch and a loud buzzing, letting me inside.

When I knocked on the door marked in tarnished numbers, 506, a tiny woman answered. She had cropped black hair that sat on her head like a cap on a pen. She was Beckman’s latest housekeeper. Ever since his beloved wife, Véra, had died years ago from cancer, Beckman, totally unable to take care of himself, hired a multitude of petite Russian women to do it for him.

They were uniformly short, severe, and middle-aged, with blue eyes, chapped hands, hair dyed the color of artificial candy, and Bolshevik Don’t even sink about it personalities. Two years ago, it was Mila, in stonewashed jeans and rhinestone T-shirts, who spoke relentlessly of a son back in Belarus. (And when she wasn’t talking about Sergio, most of what she said could be summed up with a single word: nyet. )

This one had a hawk-beak nose, wore pink dishwashing gloves and a long black rubber apron, the kind welders in factories wear for forging steel. She appeared to be wearing it to mop Beckman’s kitchen.

“He’s expecting you ?” She inspected me from head to toe. “He’s at denteest. ”

“He asked me to come in and wait.”

She squinted, skeptical, but shoved the door aside.

“You like tea ?” she demanded.

“Thank you.”

With a final look of disapproval, she disappeared into the kitchen and I stepped down the hall into the living room.

The place hadn’t changed. It was still dark and morose, smelling of dirty socks, festering humidity, and cat. Faded fleur-de-lis wallpaper, the ceiling sagging like the underside of a sofa — at Beckman’s, one always had the persistent feeling water was about to come seeping up through the wood floors. Never had I been inside an apartment so scrubbed (Beckman’s housekeeper was always armed with mop and bucket, cans of Lysol, Clorox wipes) that still felt so insistently like a bog deep in the Everglades.

I strolled to the mantel, framed pictures lined up along its edge. They, too, hadn’t changed. There was a color photo of Véra on her wedding day, beaming with joy. Next to her was a signed photograph of Marlowe Hughes, the legendary beauty and Cordova’s second wife, star of Lovechild. Beside this was a picture of Beckman’s son, Marvin, the day he graduated from law school; he looked shockingly normal. Next to him: a still from Cordova’s Thumbscrew, when Emily Jackson eyes her husband’s mysterious briefcase; a photo of Beckman, Indian-style, enthroned like a gleeful Buddha on Columbia’s Low Library steps, surrounded by fifty worshipful students.

Hanging to the right of the mantel was the framed poster of the wrinkled and creased close-up of the Cordovite’s eye. The poster had been here as long as I’d known Beckman. He’d torn it off a Pigalle Métro station wall after attending a red-band screening for Cordova’s At Night All Birds Are Black, held back in 1987 in the Parisian catacombs, one of the first events of its kind. Scribbled along the bottom by hand was the designated meeting spot: Sovereign Deadly Perfect N 48° 48 21.8594″ E 2° 18 33.3888″ 1111870300 .

A few feet to my right, in the corner, was a wooden desk and Beckman’s old Apple computer. It was humming, which meant it was actually on.

“Your tea.”

The housekeeper had materialized behind me. She slid the tray across the coffee table, glaring at me as she shoved aside a black Chinese wooden box and piles of newspapers, then stalked back into the kitchen.

I waited for her to resume cleaning, then tapped the keyboard. I wasn’t exactly proud of myself, snooping on an innocent man’s computer, but desperate times called for desperate measures.

Читать дальше