Maybe he was Charon, ferryman of the River Styx, transporting all newly dead souls into the underworld.

I turned back, staring ahead, trapped in the feeling that something was about to appear and the horror that nothing ever would. We continued on, I didn’t know how long. I couldn’t release my grip on the sides of the boat to check my watch or the compass, the waves growing violent, ocean spray soaking me as they turned upon themselves, beating the boat. Slowly I began to surrender to the possibility that we’d go on and on like this, until the gas ran out, and when it did, the boat’s motor would clear its throat like an exhausted opera singer leaving the stage, and I’d turn to find that even the old man was gone.

But when I did turn, he was still hunched there, squinting far off to our left, steering us toward another massive green-black island growing out of the horizon, this one with a narrow beach fringed with foliage and beyond that, immense cliffs rising like muscular shoulders out of the sea. The man grinned as if recognizing an old friend and when we were some twenty yards offshore, abruptly he cut the engine, staring at me expectantly as the boat pitched and jerked. I realized, as he extended one oil-blackened index finger toward the water, still smiling, it was my cue to jump.

I shook my head. “What?”

He only jabbed that finger toward the water, and when I waved my arm, trying to tell him to forget it, a heavy swell blasted the boat. Before I could brace myself, I was abruptly tossed forward.

I was spinning upside down in the freezing waves. I broke the surface, gasping, seawater filling my mouth, but as the ground found my feet I realized it was shallow. I kicked my way to shore, struggling to stand, bending over, coughing. But then I whipped around, horrified. I’d neither paid the man nor made any arrangements to get back.

He’d already restarted the motor and was circling the boat around.

“Hey!” I shouted, but again, the wind erased my voice. “ Wait! Come back!”

He didn’t react or didn’t hear me. Shoulders hunched, bracing himself against the wind, he was speeding across the water, motor screeching, and within minutes he was nothing but a speck of black on the sea.

I looked around. There was just enough light left to see, farther down the beach, where the sand narrowed as if brutally shoved aside by the cliffs, a giant boulder. It had a hole through it.

The trap of the mermaids.

Stunned, I stumbled toward it, then quickly realized that an immense flock of seagulls, their cries extinguished by the ocean, were swarming not only around the boulder but most of the shoreline, feasting on something scattered across the rocks. The rain began to fall harder, so I took off, taking refuge under the foliage fringing the beach.

I noticed, just a few yards away, a plank jutting across the sand.

A series of boards had been flung over a muddy path leading straight back into the forest. I checked the compass, the needle resolutely pointing east, and then stepped onto the wood, the mud underneath belching from my weight. I followed it, instantly hit with stagnant air, humid and thick, but also something else — a rush, a sensation that I was sliding toward something, being funneled into a hole I couldn’t climb out of and shouldn’t try. Twisted branches wound around one another growing so dense all that was left of the rain was the sound of it, like a crowd whispering overhead. I began to walk faster, and the walk became a run, the run a sprint, the uneven planks hitting my feet, some snapping in half, sending me knee-deep in mud. I didn’t stop, streaking past spider ferns and bobbing flowers, waist-thick tree roots climbing out on either side of the path, as if trying to escape. My only company appeared to be a single bird, which dogged me like a final warning, fluttering, chirping in the overgrowth until it flew right at me, black wings grazing my cheek, emitting a sharp cry before diving again into the dark. The pathway was becoming an incline, growing steeper as if trying to shake me off, but I didn’t stop, ascending so rapidly, after a while I couldn’t feel the ground under my feet.

There was a house ahead. Nestled in the trees, it looked like so many others I’d seen on the main island, battered, covered in wooden shingles, a splintered shutter dangling from a window. Gasping to catch my breath, I slung myself up onto the porch, grabbed the rusted knob, and opened the door.

It was a deserted room — stark wooden furniture, dim light, an old ceiling fan whirling overhead.

A large oil painting hung directly across from me on the wall. It was a man’s portrait, his warped and chalky face retreating into a black background as if melting. I stepped inside, then froze, my eyes drawn to movement in the far corner. There, by a wall of dark windows, sat two leather-and-wood mission chairs like waiting thrones. On a small table beside one, a cigarette was burning— Murad, no doubt — white ribbons of smoke uncoiling off the end.

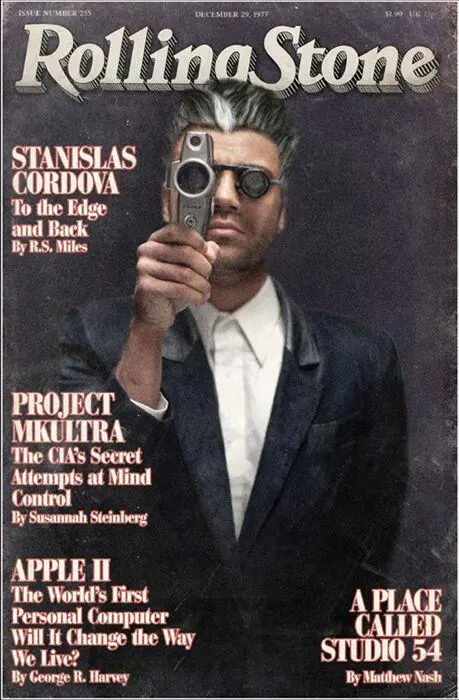

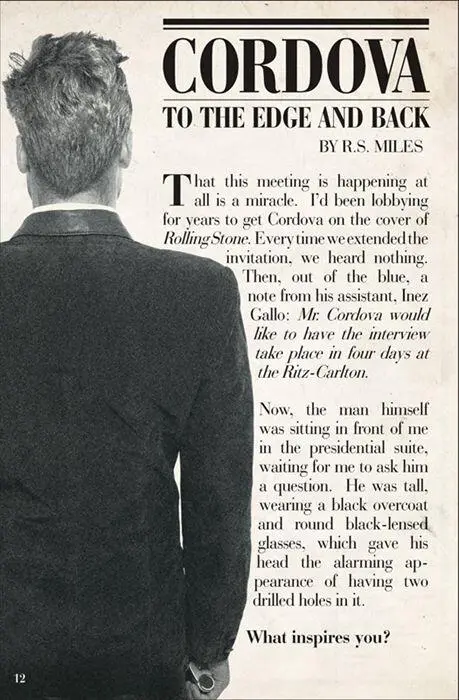

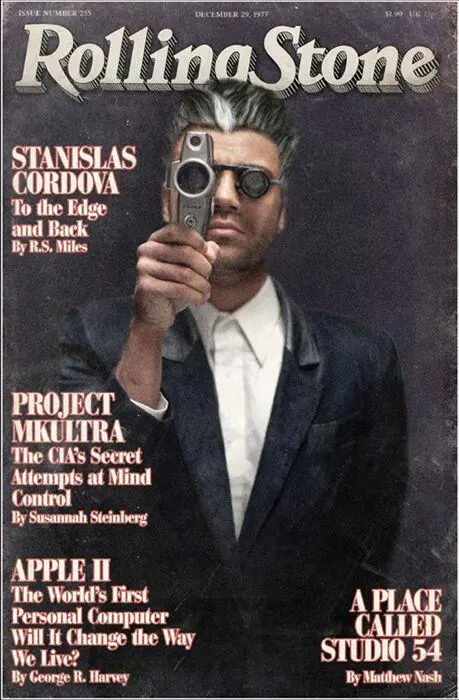

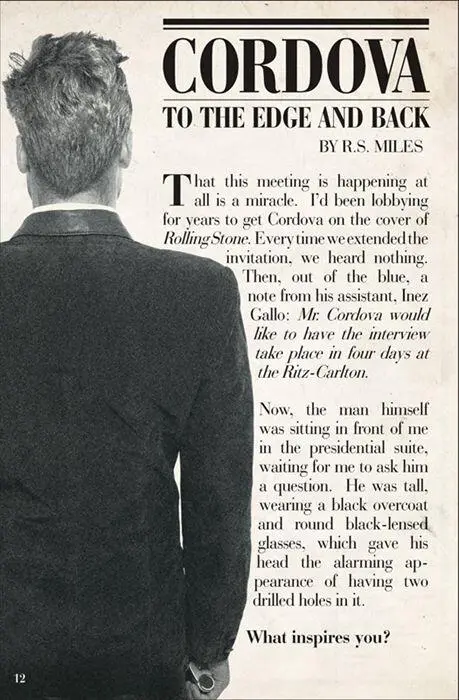

I moved toward it and spotted a pair of folded wire glasses, the lenses round and pitch black. Beside them was a bottle of Macallan scotch— my scotch, I noted with astonishment — and two empty glasses.

I turned, sensing someone watching me.

He was there, a hulking dark silhouette in the doorway.

Cordova.

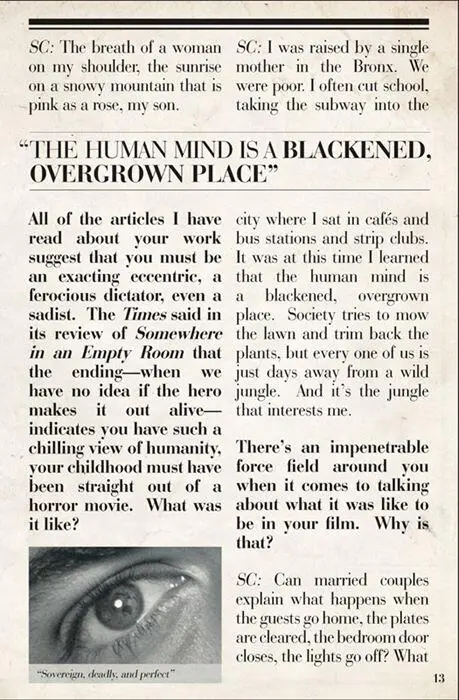

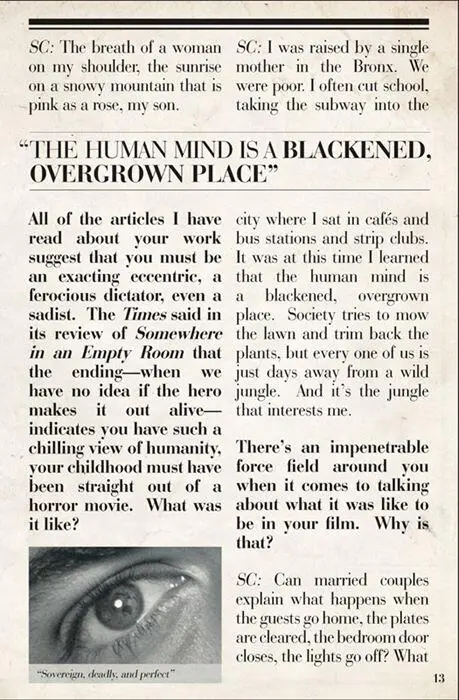

A hundred things went through my head in that moment. Hunters stare their prey in the eyes and what do they see? I hadn’t known I’d ever find him, and, if I did, whether I’d have the impulse to kill him, condemn him, or weep. Perhaps I’d pity him, brought to my knees by the vulnerable child inside every man. But I had a feeling he’d been expecting me, that we were going to do nothing more than sit down in those empty chairs, one father with another, and as the rain fell and the smoke coiled around us, weaving another hypnotic spell, he’d tell me. There would be unimaginable darkness and streaks of blood inside it, this tale he told, which would probably last for days, screams and bright red birds, and astounding hints of hope, as the sun, in an instant, can christen the blackest sea. I’d learn more about the lengths people went to feel something than I ever thought possible and I’d hear Sam’s laughter inside of Ashley’s.

I didn’t know the end or what I’d find when it was over — if I’d stare at the rubble and recognize his story as one of evil or fallen grace, or if I’d see myself in all he’d done, trying to save his daughter, in his insatiable need to stretch life as far as it would go, risking it breaking.

Somehow, I sensed as soon as he told me, he’d find a way to be gone, faster than the wind across a field. I’d wake up somewhere far away, wondering if I’d imagined it, if he’d been here at all, inside this quiet house poised at the edge of the world.

The one thing I did know, as I stepped toward him, was that he was going to sit down beside me and tell me his truth.

And I would listen.

Читать дальше