“I guess I just can’t help identifying with the guy,” Roman allows as he pokes the coals with a stick. “I hate to admit it, but not so many years ago it could easily have been me in the same kind of predicament. When I first started coming to Alaska, I think I was probably a lot like McCandless: just as green, just as eager. And I’m sure there are plenty of other Alaskans who had a lot in common with McCandless when they first got here, too, including many of his critics. Which is maybe why they’re so hard on him. Maybe McCandless reminds them a little too much of their former selves.”

Roman’s observation underscores how difficult it is for those of us preoccupied with the humdrum concerns of adulthood to recall how forcefully we were once buffeted by the passions and longings of youth. As Everett Ruess’s father mused years after his twenty-year-old son vanished in the desert, “The older person does not realize the soul-flights of the adolescent. I think we all poorly understood Everett.”

Roman, Andrew, and I stay up well past midnight, trying to make sense of McCandless’s life and death, yet his essence remains slippery, vague, elusive. Gradually, the conversation lags and falters. When I drift away from the fire to find a place to throw down my sleeping bag, the first faint smear of dawn is already bleaching the rim of the northeastern sky. Although the mosquitoes are thick tonight and the bus would no doubt offer some refuge, I decide not to bed down inside Fairbanks 142. Nor, I note before sinking into a dreamless sleep, do the others.

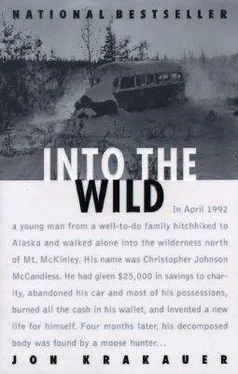

THE STAMPEDE TRAIL

It is nearly impossible for modem man to imagine what it is like to live by hunting. The life of a hunter is one of hard, seemingly continuous overland travel… A life of frequent concerns that the next interception may not work, that the trap or the drive will fail, or that the herds will not appear this season. Above all, the life of a hunter carries with it the threat of deprivation and death by starvation.

john M. campbell, the hungry summer

Now what is history? It is the centuries of systematic explorations of the riddle of death, with a view to overcoming death. That’s why people discover mathematical infinity and electromagnetic waves, that’s why they write symphonies. Now, you can’t advance in this direction without a certain faith. You can’t make such discoveries without spiritual equipment. And the basic elements of this equipment are in the Gospels. What are they? To begin with, love of one’s neighbor,which is the supreme form of vital energy. Once it fills the heart of man it has to overflow and spend itself. And then the two basic ideals of modem man-without them he is unthinkable-the idea offree personalityand the idea of life as sacrifice.

boris pasternak, doctor zhivago – passage highlighted in one of the books found with christopher mccandless’s remains;underscoring by mccandless

After his attempt to depart the wilderness was stymied by the Teklanika’s high flow, McCandless arrived back at the bus on July 8. It’s impossible to know what was going through his mind at that point, for his journal betrays nothing. Quite possibly he was unconcerned about his escape routes having been cut off; indeed, at the time there was little reason for him to worry: It was the height of summer, the country was a fecund riot of plant and animal life, and his food supply was adequate. He probably surmised that if he bided his time until August, the Teklanika would subside enough to be crossed.

Reestablished in the corroded shell of Fairbanks 142, McCandless fell back into his routine of hunting and gathering. He read Tolstoys “The Death of Ivan Ilych” and Michael Crichtons Terminal Man. He noted in his journal that it rained for a week straight. Game seems to have been plentiful: In the last three weeks of July, he killed thirty-five squirrels, four spruce grouse, five jays and woodpeckers, and two frogs, all of which he supplemented with wild potatoes, wild rhubarb, various species of berries, and large numbers of mushrooms. But despite this apparent munificence, the meat he’d been killing was very lean, and he was consuming fewer calories than he was burning. After subsisting for three months on an exceedingly marginal diet, McCandless had run up a sizable caloric deficit. He was balanced on a precarious edge. And then, in late July, he made the mistake that pulled him down.

He had just finished reading Doctor Zhivago, a book that incited him to scribble excited notes in the margins and underline several passages:

Lara walked along the tracks following a path worn by pilgrims and then turned into the fields. Here she stopped and, closing her eyes, took a deep breath of the flower-scented air of the broad expanse around her. It was dearer to her than her kin, better than a lover, wiser than a book. For a moment she rediscovered the purpose of her life. She was here on earth to grasp the meaning of its wild enchantment and to call each thing by its right name, or, if this were not within her power, to give birth out of love for life to successors who would do it in her place.

“NATURE/PURITY,” he printed in bold characters at the top of the page.

Oh, how one wishes sometimes to escape from the meaningless dullness of human eloquence, from all those sublime phrases, to take refuge in nature, apparently so inarticulate, or in the wordlessness of long, grinding labor, of sound sleep, of true music, or of a human understanding rendered speechless by emotion!

McCandless starred and bracketed the paragraph and circled “refuge in nature” in black ink.

Next to “And so it turned out that only a life similar to the life of those around us, merging with it without a ripple, is genuine life, and that an unshared happiness is not happiness… And this was most vexing of all,” he noted, “HAPPINESS ONLY REAL WHEN SHARED.”

It is tempting to regard this latter notation as further evidence that McCandless’s long, lonely sabbatical had changed him in some significant way. It can be interpreted to mean that he was ready, perhaps, to shed a little of the armor he wore around his heart, that upon returning to civilization, he intended to abandon the life of a solitary vagabond, stop running so hard from intimacy, and become a member of the human community. But we will never know, because Doctor Zhivago was the last book Chris McCandless would ever read.

Two days after he finished the book, on July 30, there is an ominous entry in the journal: “EXTREMLY WEAK. FAULT OF POT. SEED. MUCH TROUBLE JUST TO STAND UP. STARVING. GREAT JEOPARDY.” Before this note there is nothing in the journal to suggest that McCandless was in dire circumstances. He was hungry, and his meager diet had pared his body down to a feral scrawn of gristle and bone, but he seemed to be in reasonably good health. Then, after July 30, his physical condition suddenly went to hell. By August 19, he was dead.

There has been a great deal of conjecture about what caused such a precipitous decline. In the days following the identification of McCandless’s remains, Wayne Westerberg vaguely recalled that Chris might have purchased some seeds in South Dakota before heading north, including perhaps some potato seeds, with which he intended to plant a vegetable garden after getting established in the bush. According to one theory, McCand-less never got around to planting the garden (I saw no evidence of a garden in the vicinity of the bus) and by late July had grown hungry enough to eat the seeds, which poisoned him.

Potato seeds are in fact mildly toxic after they’ve begun to sprout. They contain solanine, a poison that occurs in plants of the nightshade family, which causes vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and lethargy in the short term, and adversely affects heart rate and blood pressure when ingested over an extended period. This theory has a serious flaw, however: In order for McCandless to have been incapacitated by potato seeds, he would have had to eat many, many pounds of them; and given the light weight of his pack when Gallien dropped him off, it is extremely unlikely that he carried more than a few grams of potato seeds, if he carried any at all.

Читать дальше