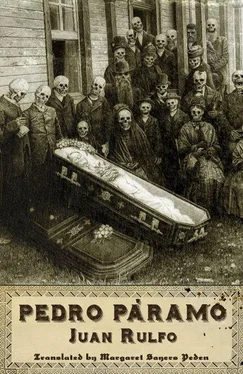

“Until tomorrow, Fausta.”

The two old women slipped through the half-open doors of their homes. And the silence of the night again fell over the village.

My mouth is filled with earth.”

“Yes, Father.”

“Don’t say, ‘Yes, Father.’ Repeat with me the words I am saying.”

“What are you going to say? You want me to confess again? Why again?”

“This isn’t a confession, Susana. I’ve just come to talk with you. To prepare you for death.”

“I’m going to die?’

“Yes, daughter.”

“Then why don’t you leave me in peace? I want to rest. Someone must have told you to come keep me awake. To stay with me until sleep is gone forever. Then what can I do to find him? Nothing, Father. Why don’t you just go away and leave me alone?”

“I will leave you in peace, Susana. As you repeat the words I tell you, you will drift off, as if you were crooning yourself to sleep. And once you are asleep, no one will wake you….

You will never wake again.”

“All right, Father. I will do what you say.”

Father Renteria, seated on the edge of the bed, his hands on Susana San Juan’s shoulders, his mouth almost touching her ear to keep from being overheard, formed each word in a secretive whisper: “My mouth is filled with earth.” Then he paused. He looked to see whether her lips were moving. He saw her mouthing words, though no sound emerged: “My mouth is filled with you, with your mouth. Your tightly closed lips, pressing hard, biting into mine….”

She, too, paused. She looked at Father Renteria from the corner of her eye; he seemed far away, as if behind a misted glass.

Again she heard his voice, warm in her ear:

“I swallow foamy saliva; I chew clumps of dirt crawling with worms that knot in my throat and push against the roof of my mouth…. My mouth caves in, contorted, lacerated by gnawing, devouring teeth. My nose grows spongy. My eyeballs liquefy. My hair burns in a single bright blaze….”

He was surprised by Susana San Juan’s calm. He wished he could divine her thoughts and see her heart struggling to reject the images he was sowing within her. He looked into her eyes, and she returned his gaze. It seemed as if her twitching lips were forming a slight smile.

“There is more. The vision of God. The soft light of his infinite Heaven. The rejoicing of the cherubim and song of the seraphim. The joy in the eyes of God, which is the last, fleeting vision of those condemned to eternal suffering. Eternal suffering joined to earthly pain. The marrow of our bones becomes like live coals and the blood in our veins threads of fire, inflicting unbelievable agony that never abates, for it is fanned constantly by the wrath of God.”

“He sheltered me in his arms. He gave me love.”

Father Renteria glanced at the figures gathered around them, waiting for the last moment. Pedro Paramo waited by the door, with crossed arms; Doctor Valencia and other men stood beside him. Farther back in the shadows, a small group of women eager to begin the prayer for the dead.

He meant to rise. To anoint the dying woman with the holy oils and say, “I have finished.”

But no, he hadn’t finished yet. He could not administer the sacraments to this woman without knowing the measure of her repentance.

He hesitated. Perhaps she had nothing to repent of. Maybe there was nothing for him to pardon. He bent over her once more and said in a low voice, shaking her by the shoulders: “You are going into the presence of God. And He is cruel in His judgment of sinners.”

Then he tried once more to speak into her ear, but she shook her head:

“Go away, Father. Don’t bother yourself over me. I am at peace, and very sleepy.”

A sob burst forth from one of the women hidden in the shadows.

Susana San Juan seemed to revive for a moment. She sat straight up in bed and said: “Justina, please go somewhere else if you’re going to cry!”

Then she felt as if her head had fallen upon her belly. She tried to lift it, to push aside the belly that was pressing into her eyes and cutting off her breath, but with each effort she sank deeper into the night.

I… I saw dona Susanita die.”

“What are you saying, Dorotea?”

“What I just told you.”

Dawn. People were awakened by the pealing of bells. It was the morning of December eighth.

A gray morning. Not cold, but gray. The pealing began with the largest bell. The others chimed in. Some thought the bells were ringing for High Mass, and doors began to open wide. Not all the doors opened; some remained closed where the indolent still lay in bed waiting for the bells to advise them that morning had come. But the ringing lasted longer than it should have.

And it was not only the bells of the large church, but those in Sangre de Cristo, in Cruz Verde, and the Santuario. Noon came, and the tolling continued. Night fell. And day and night the bells continued, all of them, stronger and louder, until the ringing blended into a deafening lament. People had to shout to hear what they were trying to say. “What could it be?” they asked each other.

After three days everyone was deaf. It was impossible to talk above the clanging that filled the air. But the bells kept ringing, ringing, some cracked, with a hollow sound like a clay pitcher.

“Dona Susana died.”

“Died? Who?”

“The senora.”

“Your senora?”

“Pedro Paramo’s senora.”

People began arriving from other places, drawn by the endless pealing. They came from Contla, as if on a pilgrimage. And even farther. A circus showed up, who knows from where, with a whirligig and flying chairs. And musicians. First they came as if they were onlookers, but after a while they settled in and even played concerts. And so, little by little, the event turned into a fiesta. Comala was bustling with people, boisterous and noisy, just like the feast days when it was nearly impossible to move through the village.

The bells fell silent, but the fiesta continued. There was no way to convince people that this was an occasion for mourning. Nor was there any way to get them to leave. Just the opposite, more kept arriving.

The Media Luna was lonely and silent. The servants walked around with bare feet, and spoke in low voices. Susana San Juan was buried, and few people in Comala even realized it. They were having a fair. There were cockfights and music, lotteries, and the howls of drunken men. The light from the village reached as far as the Media Luna, like an aureole in the gray skies. Because those were grey days, melancholy days for the Media Luna. Don Pedro spoke to no one. He never left his room. He swore to wreak vengeance on Comala: “I will cross my arms and Comala will die of hunger.” And that was what happened.

El Tilcuajte continued to report: —“With Carranza now.”

“Fine.”

“Now we’re riding with General Obregon.”

“Fine.”

“They’ve declared peace. We’re dismissed.”

“Wait. Don’t disband your men. This won’t last long.”

“Father Renteria’s fighting now. Are we with him or against him?”

“No question. You’re on the side of the government.”

“But we’re irregulars. They consider us rebels.”

“Then take a rest.”

“As fired up as I am?”

“Do what you want, then.”

“I’m going to back that old priest. I like how they yell. Besides, that way a man can be sure of salvation.”

“I don’t care what you do.”

Pedro Paramo was sitting in an old chair beside the main door of the Media Luna a little before the last shadow of night slipped away. He had been there, alone, for about three hours. He didn’t sleep anymore. He had forgotten what sleep was, or time. “We old folks don’t sleep much, almost never. We may drowse, but our mind keeps working. That’s the only thing I have left to do.” Then he added, aloud: “It won’t be long now. It won’t be long.”

Читать дальше