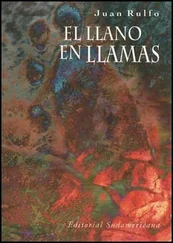

“Go with God.”

He rapped on the window of the confessional to summon another of the women. And while he listened to “I have sinned,” his head slumped forward as if he could no longer hold it up. Then came the dizzyness, the confusion, the slipping away as if in syrupy water, the whirling lights; the brilliance of the dying day was splintering into shards. And there was the taste of blood on his tongue. The “I have sinned” grew louder, was repeated again and again: “for now and forever more,”

“for now and forever more,”

“for now…”

“Quiet, woman,” he said. “When did you last confess?”

“Two days ago, padre.”

Yet she was back again. It was as if he were surrounded by misfortune. What are you doing here, he asked himself. Rest. Go rest. You are very tired.

He left the confessional and went straight to the sacristy. Without a glance for the people waiting, he said:

“Any of you who feel you are without sin may take Holy Communion tomorrow.”

Behind him, as he left, he heard the murmuring.

I am lying in the same bed where my mother died so long ago; on the same mattress, beneath the same black wool coverlet she wrapped us in to sleep. I slept beside her, her little girl, in the special place she made for me in her arms.

I think I can still feel the calm rhythm of her breathing; the palpitations and sighs that soothed my sleep…. I think I feel the pain of her death…. But that isn’t true.

Here I lie, flat on my back, hoping to forget my loneliness by remembering those times.

Because I am not here just for a while. And I am not in my mother’s bed but in a black box like the ones for burying the dead. Because I am dead.

I sense where I am, but I can think….

I think about the limes ripening. About the February wind that used to snap the fern stalks before they dried up from neglect. The ripe limes that filled the overgrown patio with their fragrance.

The wind blew down from the mountains on February mornings. And the clouds

gathered there waiting for the warm weather that would force them down into the valley.

Meanwhile the sky was blue, and the light played on little whirlwinds sweeping across the earth, swirling the dust and lashing the branches of the orange trees.

The sparrows were twittering; they pecked at the wind-blown leaves, and twittered.

They left their feathers among the thorny branches, and chased the butterflies, and twittered. It was that season.

February, when the mornings are filled with wind and sparrows and blue light. I remember. That is when my mother died.

I should have wailed. I should have wrung my hands until they were bleeding. That is how you would have wanted it. But in fact, wasn’t that a joyful morning? The breeze was blowing in through the open door, tearing loose the ivy tendrils. Hair was beginning to grow on the mound between my legs, and my hands trembled hotly when I touched my breasts. Sparrows were playing. Wheat was swaying on the hillside. I was sad that she would never again see the wind playing in the jasmines; that her eyes were closed to the bright sunlight. But why should I weep?

Do you remember, Justina? You arranged chairs in a row in the corridor where the people who came to visit could wait their turn. They stood empty. My mother lay alone amid the candles; her face pale, her white teeth barely visible between purple lips frozen by the livid cold of death.

Her eyelashes lay still; her heart was still. You and I prayed interminable prayers she could not hear, that you and I could not hear above the roar of the wind in the night. You ironed her black dress, starched her collar and the cuffs of her sleeves so her hands would look young crossed upon her dead breast — her exhausted, loving breast that had once fed me, that had cradled me and throbbed as she crooned me to sleep.

No one came to visit her. Better that way. Death is not to be parceled out as if it were a blessing. No one goes looking for sorrow.

Someone banged the door knocker. You went to the door.

“You go,” I said. “I see people through a haze. Tell them to go away. Have they come for money for the Gregorian masses? She didn’t leave any money. Tell them that, Justina. Will she have to stay in purgatory if they don’t say those masses? Who are they to mete out justice, Justina? You think I’m crazy? That’s fine.”

And your chairs stood empty until we went to bury her, accompanied by the men we had hired, sweating under a stranger’s weight, alien to our grief. They shoveled damp sand into the grave; they lowered the coffin, slowly, with the patience of their office, in the breeze that cooled them after their labors. Their eyes cold, indifferent. They said: “It’ll be so much.” And you paid them, the way you might buy something at the market, untying the corner of the tear-soaked handkerchief you’d wrung out again and again, the one that now contained the money for the burial….

And when they had gone away, you knelt on the spot above her face and you kissed the ground, and you would have dug down toward her if I hadn’t said: “Let’s go, Justina. She isn’t here now. There’s nothing here but a dead body.”

“That you talking, Dorotea?”

“Who, me? I was asleep for a while. Are you still afraid?”

“I heard someone talking. A woman’s voice. I thought it was you.”

“A woman’s voice? You thought it was me? It must be that woman who talks to herself.

The one in the large tomb. Dona Susanita. She’s buried close to us. The damp must have got to her, and she’s moving around in her sleep.”

“Who is she?”

“Pedro Paramo’s last wife. Some say she was crazy. Some say not. The truth is that she talked to herself even when she was alive.”

“She must have died a long time ago.”

“Oh, yes! A long time ago. What did you hear her say?”

“Something about her mother.”

“But she didn’t have a mother…. ”

“Well, it was her mother she was talking about.”

“Hmmm. At least, her mother wasn’t with her when she came. Wait a minute. I remember now the mother was born here, and when she was getting along in years, they vanished. Yes, that’s it. Her mother died of consumption. She was a strange woman who was always sick and never visited with anyone.”

“That’s what she was saying. That no one had come to visit her mother when she died.”

“What did she mean? No wonder no one wanted to step inside her door, they were afraid of catching her disease. I wonder if the Indian woman remembers?”

“She was talking about that.”

“When you hear her again, let me know. I’d like to know what she’s saying.”

“You hear? I think she’s about to say something. I hear a kind of murmuring.”

“No, that isn’t her. That’s farther away and in the other direction. And that’s a man’s voice. What happens with these corpses that have been dead a long time is that when the damp reaches them they begin to stir. They wake up.”

“The heavens are bountiful. God was with me that night. If not, who knows what might have happened. Because it was already night when I came to…. ”

“You hear it better now?”

“Yes.”

“…I was covered with blood. And when I tried to get up my hands slipped in the puddles of blood in the rocks. It was my blood. Buckets of blood. But I wasn’t dead. I knew that. I knew that don Pedro hadn’t meant to kill me. Just give me a scare. He wanted to find out whether I’d been in Vilmayo that day two years before. On San Cristobal’s day.

At the wedding. What wedding? Which San Cristobal’s? There I was slipping around in my own blood, and I asked him just that: ‘What wedding, don Pedro? No! No, don Pedro. I wasn’t there. I may have been near there, but only by chance….’ He never meant to kill me.

Читать дальше