She left, and I was certain nothing would be done. That night two of my roommates had a fight. They punched and kicked and hurled everything that came to hand. A three-foot-tall clay jug shattered, sloshing water across the floor. Mirrors and a picture of Shiva and Parvati smashed against the wall. Handfuls of hair flew in the air.

Four supervisors plus a male sentry finally pulled them apart. Meanwhile they'd made a shambles of our room, and I had to sleep in the dormitory. Hard wooden bed beneath me; sixty breathing, snoring, coughing, crying-in-their-sleep Indian girls around me, the nearest one with her underpants around her knees, masturbating all night. And I'd wanted an adventure!

In the morning the social worker rescued me. She escorted me by jeep to the courthouse and arranged my return to Tihar. I gave her an enormous hug.

Ah, Tihar! You'd have thought I'd been granted entrance to the Garden of Eden.

"Frin! Marie-Andree!" I rushed into my friends' arms.

I had to be the happiest person on the planet. Marie-Andree gave me the opium that had arrived two minutes after I'd been taken away. The servant cooked a scrumptious dinner. I had my old room back.

I pulled the mattress to the front of my cell to sleep under the stars. As I lay watching their brightness through the striped outline of bars, I contemplated the state of affairs that had made returning to New Delhi's Tihar Jail such a blissful event. Somewhere along the line I'd lost control of my life. Not to mention my finances. How was I going to pay Lino the rent? I still owed him for last year. I seemed on the verge of losing everything, including control, caution, and good sense. Maybe it was time to leave India.

NO.

India was my home. Besides, with the monsoon nearing its end, a new Goa season awaited.

After another week Rachid bailed me out.

Since it was already September, Rachid agreed it was time for me to reopen my dope den in Goa. My court case wasn't finished yet, and the New Delhi police still had my passport, but legal things took time, and the lawyer could take care of details while I was away. I wasn't about to stay in Delhi while a new season began in Goa.

In Bombay I delighted in finding real people, my people—not the unsavoury types Rachid had working for him. In a suite at the Nataraj Hotel I found Junky Robert and Tish and their new baby. Finished with her motherly duty of giving birth, Tish was snorting dope again.

Rich once more, Robert and Tish had established a legitimate business, importing cane furniture into Florida. They passed me lines of coke while describing the condo they'd bought in Miami Beach. Robert lectured on the wonders of Singapore cane chairs, then segued into a harangue on the benefits of family life.

"I'm a father now. I have to think about her," he said, lifting a gold razor blade from the coke and aiming it at the baby.

Tish and Robert still owed me money from the scam I'd invested in two years before. I didn't have to remind them—they handed me a thousand dollars in cash, plus a generous stash of dope.

The next morning I changed dollars at a black-market exchange in Colaba, bought a flea collar for Bach from a black-market dealer in Crawford Market, and took the boat to Goa. Hallelujah, I was headed home!

Fifth Season in Goa

1979 — 1980

"BACH! BACH!" I WRAPPED my arms around the writhing bundle of fur that bounded into them "Oh, Bach. Look how big you've grown. Bach, I missed you so."

Since I'd cabled my arrival date to the maid, the house was fixed and waiting. I closed the front door and sat on the inside steps as furry animal jumped all over me. Oh, Bach, I don't ever want to leave you again. I don't ever want to leave this house again. I love this place. How am I going to pay the rent?

Lino arrived within an hour. Amazing how news can travel fast without a telephone.

"The money's on the way," I promised him. "It's been sent from New York. Should be here any day."

How could I possibly amass the two years rent I owed him? I wouldn't think about it now. As long as I had Bach and the house and the beach, everything was just wonderful. For the moment, at least.

I put on a slinky red and gold Chinese dress and dyed Bach's tail and one of his legs with red food colouring. I made his ears gold. Then, shouldering a red parasol, I headed for Joe Banana's. Cleo was back.

I stopped by Alehandro's, Sasha's, Kurt's tree, and Eight-Finger Eddy's porch. I joined the gang at the south end to watch the sunset, and then a group of us went to Gregory's restaurant for buffalo steak. Bach ate prawns in wine sauce. I was home. I loved Anjuna Beach—every grain of sand, each palm tree, and every water buffalo. It was impossible to love anything more than I loved Anjuna Beach.

The next day I visited Canadian Jacques, Norwegian Monica, and Pharaoh. Pans and Paul, together again, were renting their same house by Joe Banana's. Siena and Bernard lived in a new one behind the paddy fields. Graham had returned next door. The beach parties resumed at the south end.

Home.

But the dope den never regained its vigour. During the previous year's high season it had been a tremendous success. This year it never got off the ground. Oh, I sold a lot. But I also consumed a lot, and somehow the two couldn't keep nice. My enthusiasm for the enterprise evaporated. It required so much work. It was no longer a challenge—just a hassle. I couldn't even show the movies since they, along with the projector, were still being held hostage by the hospital, awaiting payment of Maria's bill.

I lacked stamina. I barely had the strength to go to the south end for a swim. For the first time I used the beach in back of the house. Previously I'd swam there only in a heat emergency. The south end was the place to hang out; the middle beach was for tourists who didn't know better.

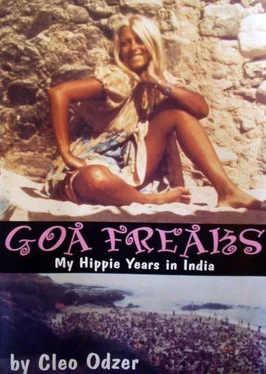

Come to think of it, the south end had become less popular over the pass few years. When I'd first arrived Goa Freaks packed its shores every day. As of Tate, though, more and more people stayed away, preferring to remain indoors, around the bhong, smoking dope. There hadn't been a crowd at the south end in a long time. Whatever happened to the volleyball net, I wondered?

So now I swam at the middle beach, with its hidden jagged rocks waiting for a toe to scrape. I took Bach in the water with me. When the colour washed out of his fur, I coloured him again. I'd match him to whatever I wore that day. When I dressed in purple, Bach wagged a purple tail.

One day a catastrophe befell my area—they found a dead French Junky in the well. Nobody knew who he was. He must have stumbled into it during the night and drowned. The well was now polluted, ruined. The Goans living nearby depended entirely on that well. This was a major disaster.

It took the Goans three days to haul out the water and dredge up the bottom mud. Besides the inconvenience, to the superstitious Catholic natives a dead person in your drinking water was considered as bad an omen as you could get. They said it would be years before the well could be used again. In the meantime we'd have to use the one on the other side of Graham's house, by the paddy field—a arduous trek when carrying a bucket of water. Now it wasn't easy to find Goans willing to fill my water tank. One flush of the toilet cost two trips to the well. I'd have to ask my customers to use the outdoor pig-as-waste-disposal toilet.

Rachid's man wouldn't deliver to my door; I had to make the long journey into Mapusa for daily drug supplies. Hassle. I worried about the customers I was losing while I was away.

Then I realized my biggest problem: The Sikh chai shop.

During the monsoon a new chai shop had opened on the other side of Graham's house. I'd noticed their building of brick and palm fronds when I'd first returned. The Sikhs served Chicken Tikka and Chicken Masala, along with dope, coke, hash, and morphine. If customers came while I was out, they didn't wait; they bought from the Sikhs instead. The price was the same and the quality not much different.

Читать дальше