“It always has been.”

“Don’t you hate it?”

“I hate it and I always have hated it. But when you have to do it you ought to know how. That was a frontal attack. They are just murder.”

“Are there other ways to attack?”

“Oh sure. Lots of them. But you have to have knowledge and discipline and trained squad and section leaders. And most of all you ought to have surprise.”

“It makes now too dark to work,” Johnny said putting the cap over his telephoto lens. “Hello you old lice. Now we go home to the hotel. Today we work pretty good.”

“Yes,” said the other one. “Today we have got something very good. It is too dom bad the attack is no good. Is better not to think about it. Sometime we film a successful attack. Only always with a successful attack it rains or snows.”

“I don’t want to see any more ever,” the girl said. “I’ve seen it now. Nothing would ever make me see it for curiosity or to make money writing about it. Those are men as we are. Look at them there on that hillside.”

“You are not men,” said Johnny. “You are a womans. Don’t make a confusion.”

“Comes now the steel hat man,” said the other looking out of the window. “Comes now with much dignity. I wish I had bomb to throw to make suddenly a surprise.”

We were packing up the cameras and equipment when the steel-hatted Authority came in.

“Hullo,” he said. “Did you make some good pictures? I have a car in one of the back streets to take you home, Elizabeth.”

“I’m going home with Edwin Henry,” the girl said.

“Did the wind die down?” I asked him conversationally.

He let that go by and said to the girl, “You won’t come?”

“No,” she said. “We are all going home together.”

“I’ll see you at the Club tonight,” he said to me very pleasantly.

“You don’t belong to the Club any more,” I told him, speaking as nearly English as I could.

We all started down the stairs together, being very careful about the holes in the marble, and walking over and around the new damage. It seemed a very long stairway. I picked up a brass nose-cap flattened and plaster marked at the end and handed it to the girl called Elizabeth.

“I don’t want it,” she said and at the doorway we all stopped and let the steel-hatted man go on ahead alone. He walked with great dignity across the part of the street where you were sometimes fired on and continued on, with dignity, in the shelter of the wall opposite. Then, one at a time, we sprinted across to the lee of the wall. It is the third or fourth man to cross an open space who draws the fire, you learn after you have been around a while, and we were always pleased to be across that particular place.

So we walked up the street now, protected by the wall, four abreast, carrying the cameras and stepping over the new iron fragments, the freshly broken bricks, and the blocks of stone, and watching the dignity of the walk of the steel-hatted man ahead who no longer belonged to the Club.

“I hate to write a dispatch,” I said. “It’s not going to be an easy one to write. This offensive is gone.”

“What’s the matter with you, boy?” asked Johnny.

“You must write what can be said,” the other one said gently. “Certainly something can be said about a day so full of events.”

“When will they get the wounded back?” the girl asked. She wore no hat and walked with a long loose stride and her hair, which was a dusty yellow in the fading light, hung over the collar of her short, fur-collared jacket. It swung as she turned her head. Her face was white and she looked ill.

“I told you as soon as it gets dark.”

“God make it get dark quick,” she said. “So that’s war. That’s what I’ve come here to see and write about. Were those two men killed who went out with the stretcher?”

“Yes,” I said. “Positively.”

“They moved so slowly ,” the girl said pitifully.

“Sometime’s it’s very hard to make the legs move,” I said. “It’s like walking in deep sand or in a dream.”

Ahead of us the man in the steel hat was still walking up the street. There was a line of shattered houses on his left and the brick wall of the barracks on his right. His car was parked at the end of the street where ours was also standing in the lee of a house.

“Let’s take him back to the Club,” the girl said. “I don’t want anyone to be hurt tonight. Not their feelings nor anything. Heh!” she called. “Wait for us. We’re coming.”

He stopped and looked back, the great heavy helmet looking ridiculous as he turned his head, like the huge horns on some harmless beast. He waited and we came up.

“Can I help you with any of that?” he asked.

“No. The car’s just there ahead.”

“We’re all going to the Club,” the girl said. She smiled at him. “Would you come and bring a bottle of something?”

“That would be so nice,” he said. “What should I bring?”

“Anything,” the girl said. “Bring anything you like. I have to do some work first. Make it seven thirtyish.”

“Will you ride home with me?” he asked her. “I’m afraid the other car is crowded with all that bit.”

“Yes,” she said. “I’d like to. Thank you.”

They got in one car and we loaded all the stuff into the other.

“What’s the matter, boy?” Johnny said. “Your girl go home with somebody else?”

“The attack upset her. She feels very badly.”

“A woman who doesn’t upset by an attack is no woman,” said Johnny.

“It was a very unsuccessful attack,” said the other. “Fortunately she did not see it from too close. We must never let her see one from close regardless of the danger. It is too strong a thing. From where she saw it is only a picture. Like old-fashioned battle scene.”

“She has a kind heart,” said Johnny. “Different than you, you old lice.”

“I have a kind heart,” I said. “And it’s louse. Not lice. Lice is the plural.”

“I like lice better,” said Johnny. “It sounds more determined.”

But he put up his hand and rubbed out the words written in lipstick on the window.

“We make a new joke tomorrow,” he said. “It’s all right now about the writing on the mirror.”

“Good,” I said. “I’m glad.”

“You old lice,” said Johnny and slapped me on the back.

“Louse is the word.”

“No. Lice. I like much better. Is many times more determined.”

“Go to hell.”

“Good,” said Johnny, smiling happily. “Now we are all good friends again. In a war we must all be careful not to hurt each other’s feelings.”

I Guess Everything Reminds You of Something

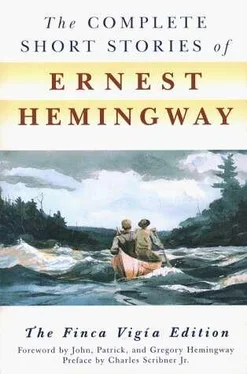

“I Guess Everything Reminds You of Something” is a completed short story set in Cuba, where Hemingway made his home at the Finca Vigía from 1939 to 1959.

“IT’S A VERY GOOD STORY,” THE BOY’S father said. “Do you know how good it is?”

“I didn’t want her to send it to you, Papa.”

“What else have you written?”

“That’s the only story. Truly I didn’t want her to send it to you. But when it won the prize—”

“She wants me to help you. But if you can write that well you don’t need anyone to help you. All you need is to write. How long did it take you to write that story?”

“Not very long.”

“Where did you learn about that type of gull?”

“In the Bahamas I guess.”

“You never went to the Dog Rocks nor to Elbow Key. There weren’t any gulls nor terns nested at Cat Key nor Bimini. At Key West you would only have seen least terns nesting.”

“Killem Peters. Sure. They nest on the coral rocks.”

Читать дальше