In the course of the twenty-five years between his 1917 and 1942 army registrations, Toomer was endlessly deconstructing his Negro ancestry. We recall that during his childhood and adolescence in Washington, D.C., and New York, Toomer lived in both the white and the black worlds, and here we must emphasize the fact that during his adolescence he was educated and lived in the world occupied by Washington’s black and mulatto elite. Based upon his experiences in this special world “midway between the white and Negro worlds,” 158Toomer claimed that he developed his famous “racial position” in 1914, when he says he first defined himself as an “American, neither white nor black,” just a year after declaring himself to be a Negro in his first draft registration. But given the fact that his parents and grandparents identified themselves and Toomer (in the 1900 and 1910 federal censuses) as black, it is apparent that Toomer’s feelings about his racial identity were anomalous within his own family.” 159It is important to stress that the first short story Toomer ever wrote, “Bona and Paul,” composed in 1918, takes passing as its central theme, and that this deeply autobiographical story reflects Toomer’s early preoccupation with his racial identity.

Equally important, Toomer’s assertion that “Kabnis is me,” in his well-known December 1922 letter to Waldo Frank concerning his relationship to a character of mixed-race ancestry who is deeply conflicted about his Negro ancestry, is further evidence of his ambivalence regarding his racial identity. This ambivalence about his black ancestry is also reflected in the controversial launch of Cane , specifically his conflicted, indeed angry reaction to Waldo Frank’s introduction, and later his refusal to cooperate with Horace Liveright, his publisher, in “featuring Negro” in the marketing of Cane in the fall of 1923. Indeed, he all but said to Liveright: “I was not a Negro.” 160According to Darwin Turner, Toomer, in his correspondence with the writer Sherwood Anderson just a year before the publication of Cane , “never opposed Anderson’s obvious assumption that he was ‘Negro.’ In fact, Anderson began the correspondence because Toomer had been identified to him as a ‘Negro.’” 161Toomer’s contradictory stance vis-à-vis Liveright and Anderson reveals the depth of his anguish about his race in the weeks before the publication of the work that would link him to a literary tradition from which he would fee.

We also must recall Toomer’s anger with Alain Locke for reprinting excerpts of Cane in The New Negro in 1925 (he was silent regarding Locke’s decision to reprint “Song of the Son” in the 1925 Harlem issue of The Survey Graphic ), a reaction that smacks of denial and ingratitude, given Locke’s early and consistent support of Toomer while he was still living in Washington, D.C. And then in 1934, almost ten years after the publication of The New Negro , Toomer, most improbably, observes to the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper that “I have not lived as [a Negro] nor do I really know whether there is colored blood in me or not.” 162During this same period, Toomer refuses to contribute to Nancy Cunard’s anthology The Negro (1934) stating that “though I am interested in and deeply value the Negro, I am not a Negro.” 163This claim stands out as particularly disingenuous when we recall Toomer’s week-long trip with Waldo Frank in the fall of 1922 in Spartanburg, South Carolina, where they masqueraded as “blood brothers,” that is, as Negroes. 164After serving as Frank’s “host in a black world,” 165Toomer returned to Washington, and for two weeks worked as an assistant to the manager of the Howard Theater, a theater that served the capital’s African American community, and where he gathered material for such stories as “Box Seat” and “Theater.” These shaping experiences in the black world, among many others, call into question Toomer’s odd claim in the Baltimore Afro-American and to the anthologist Nancy Cunard that he was not, and had not been, black.

At this juncture, it is useful to return to Elizabeth Alexander’s “Toomer,” the splendid poem that opens our introduction and that also evokes Toomer’s shifting, complex, contradictory stance on race: “I wished / to contemplate who I was beyond / my body, this container of flesh. / I made up a language in which to exist. /…Oh, / to be a Negro is — is? / to be a Negro, is. To be.” 166Alexander’s key line is this: “I made up a language in which to exist.” In this insightful line, Alexander captures not only Toomer’s definition of race as a social construction, but also his anguished effort to liberate himself from his apparent anxiety and ambivalence about his black ancestry.

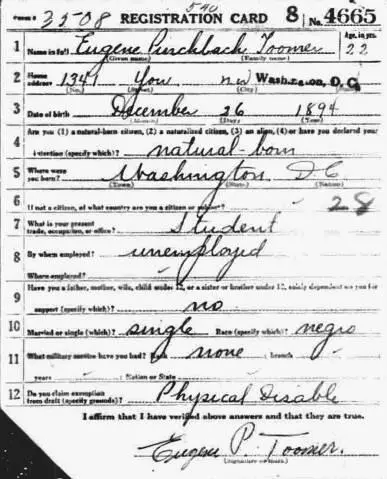

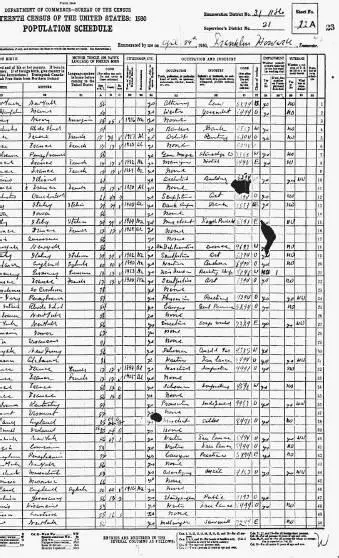

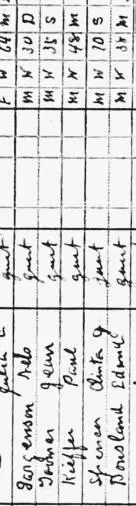

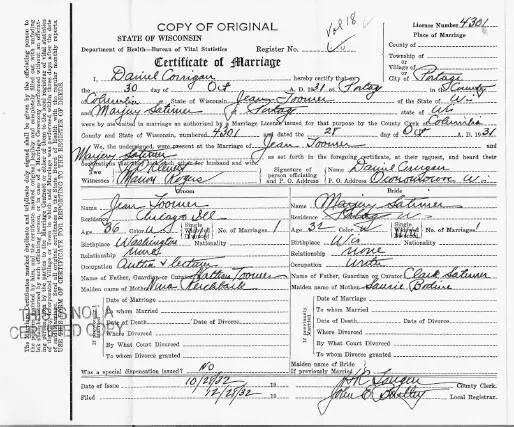

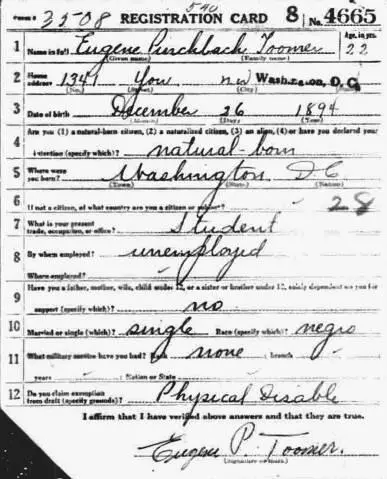

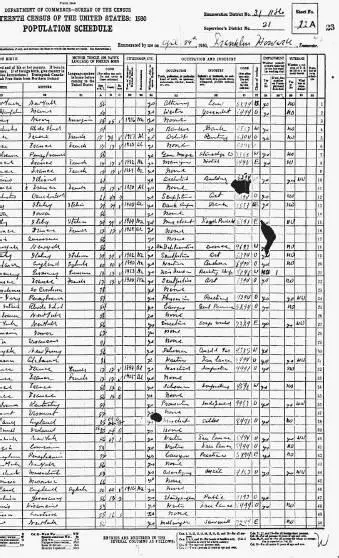

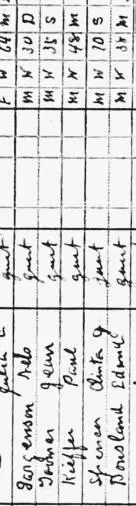

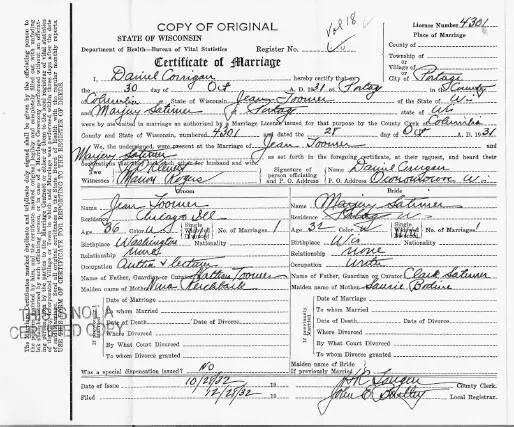

Not withstanding Toomer’s definition of himself as an “American, neither white nor black,” 167at crucial stages in his life he self-identified as Negro: as a young adult in 1917 at the age of 23, Toomer self-identified as Negro; again in 1942 as a mature adult at the age of 48, Toomer self-identified as Negro. While the registration cards, the census data, and marriage certificate are contradictory, there is, nevertheless, a pattern. It is our carefully considered judgment, based upon an analysis of archival evidence previously overlooked by other scholars, that Jean Toomer — for all of his pioneering theorizing about what today we might call a multicultural or mixed-raced ancestry — was a Negro who decided to pass for white. Here we respectfully disagree with Toomer’s biographers Kerman and Eldridge, who claim that Toomer never attempted “to ‘pass’ in a racial sense.” 168

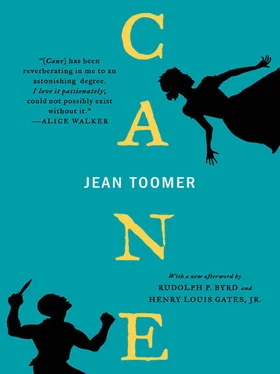

And what is Toomer’s relationship to American modernism and the African American literary tradition? Without question, Cane is a classic work of timeless significance in American and African American letters. In its pages we encounter again and again the arresting vision of an astonishingly original writer. And what shall be our generation’s relationship to this great artist of the Harlem Renaissance and the Lost Generation, who rejected the very book by which he is destined to be remembered? Alice Walker expressed a perspective we would do well to reflect upon. Shortly after the publication of Meridian , her magisterial fictional meditation on the civil rights movement, and her own formal response to Toomer’s call in Cane , Walker concluded: “I think Jean Toomer would want us to keep [ Cane ’s] beauty, but let him go.” 169Walker is probably correct in her assessment of Toomer’s own wishes. However, since Toomer’s Cane is arguably the most sophisticated work of literature created over the course of the Harlem Renaissance, we imagine that future generations of scholars will find his struggle with his racial identity as endlessly fascinating as we have.

Toomer’s draft registration, June 5, 1917.

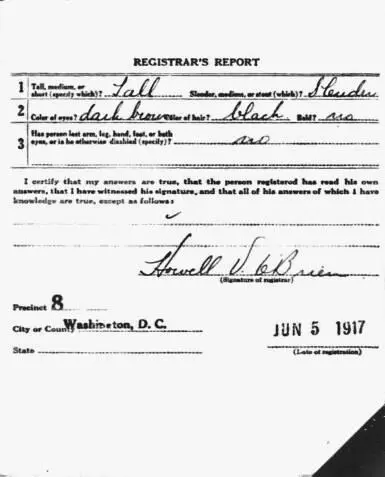

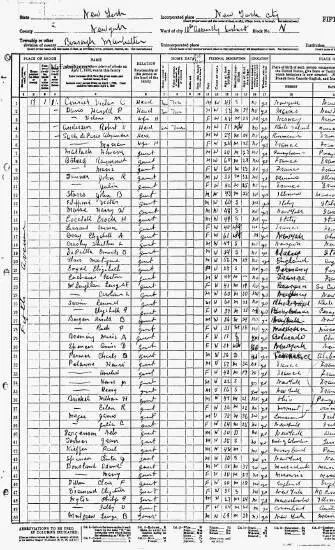

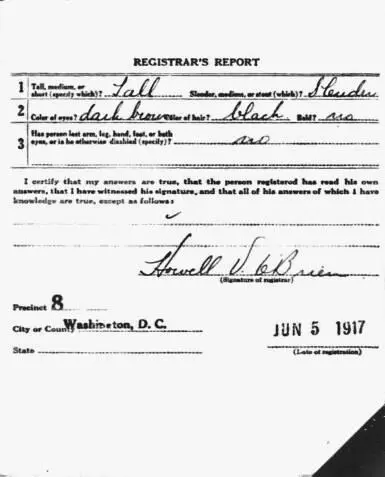

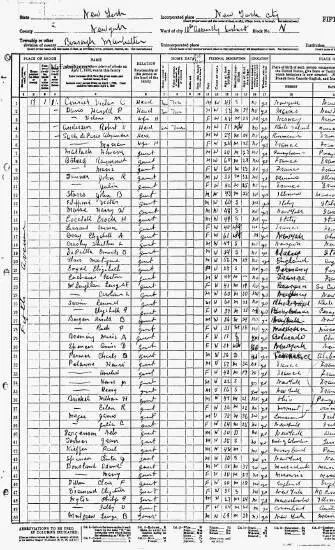

1930 census

Detail of 1930 census.

Читать дальше