Toomer arrived at his definition of his own race when most Americans implicitly accepted a “scientific” or biological definition of race, and believed that the world was composed of several distinct racial groups, each with its own history, each with its own place in a racial hierarchy, each with its own special contribution to make to world civilization. W. E. B. Du Bois’s essay, “The Conservation of Races” (1896), theorizes race as a biological or natural concept, but rejects a racial hierarchy, assigning to the Negro a positive value and function among the world’s races: “We are that people whose subtle sense of song has given America its only American music, its only American fairy tales, its only touch of pathos and humor amid its mad money-getting plutocracy.” 72He would later dismiss “The Conservation of Races” as an instance of “youthful effusion.” 73In Dusk of Dawn (1940), Du Bois revisited the question of race, abandoning the biological or scientific concept of race: “Perhaps it is wrong to speak of it at all as ‘a concept’ rather than as a group of contradictory forces, facts and tendencies.” 74In this final definition, Du Bois theorized race as a social construct. In doing so, he prepared the ground for a subsequent generation of scholars — Kwame Anthony Appiah, Jacqueline Nassy Brown, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Paul Gilroy, Stuart Hall, Patricia Williams — who would build upon Du Bois’s insight, and theorize race as a social construction or floating signifier. In Du Bois’s writing, we witness the evolution of race from a biological concept to a discursive concept. But unlike Toomer, Du Bois heartily embraced a Negro social and cultural identity, never using its constructed nature as an excuse to “transcend” it; rather to de-biologize or de-essentialize it.

Toomer observed that “it is even more difficult to determine the nature of a man; so most of us are even more content to have a label for him.” 75In an era when the views of such white supremacists as Lothrop Stoddard and Earnest Cox were in the ascendancy and referenced even in such fictional works as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby , Toomer proclaimed that in “my body were many bloods, some dark blood, all blended in the fire of six or more generations. I was, then, either a new type of man or the very oldest. In any case I was inescapably myself…. As for myself, I would live my life as far as possible on the basis of what was true for me.” 76While Toomer’s metaphor of “bloods” recalls a biological conception of race, the direction of his thinking is toward a discursive concept of race. Toomer developed the following plan for its use in the protean, contested world of social relations: “To my real friends of both groups, I would, at the right time, voluntarily define my position. As for people at large, naturally I would go my way and say nothing unless the question was raised. If raised, I would meet it squarely, going into as much detail as seemed desirable for the occasion. Or again, if it was not the person’s business I would either tell him nothing or the first nonsense that came into my head.” 77It would be left to him, not to others, to define and to determine his location in the social world, or so he imagined. Toomer would soon come to realize the limitations of his own power to shape the manner in which he would be perceived and defined by others, notwithstanding the appeal of his person and personality, and his great confidence in his ability to explain and to rationalize himself.

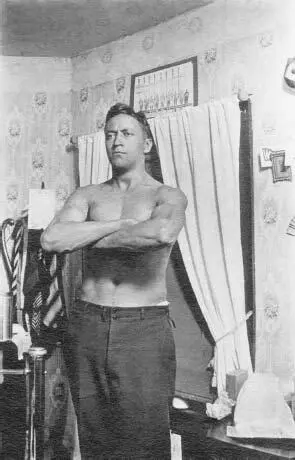

After graduating from Dunbar High School in January 1914, Toomer matriculated at six colleges and universities between 1914 and 1918, but failed to earn a degree. He attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and the Massachusetts College of Agriculture to pursue his interests in scientific agriculture. No longer interested in becoming a farmer, he pursued his new passion for exercise and bodybuilding at the American College of Physical Training in Chicago in January 1916. Toomer remained in Chicago through the fall and enrolled in courses that introduced him to atheism and socialism at the University of Chicago. In the spring of 1917 he decided to travel to New York, and there enrolled in summer school at New York University and the City College of New York where, respectively, he took a course in sociology and history. “Opposed to war but attracted to soldiering,” wrote Kerman and Eldridge, Toomer volunteered for the army, but he was “classified as physically unfit ‘because of bad eyes and a hernia gotten in a basketball game.’” 78As we reveal in “Jean Toomer’s Racial Self-Identifcation,” Toomer registered as a Negro.

In 1918, Toomer returned to the Midwest, where he held a series of odd jobs, including becoming a car salesman at a Ford dealership in Chicago. During this second period in Chicago, he wrote “Bona and Paul,” his first short story, in which he explored questions of passing and mixed-race identity, a powerful work that would eventually find its way into the second section of Cane. In February 1918, Toomer accepted an appointment in Milwaukee as a substitute physical education director, and continued his readings in literature, especially the works of George Bernard Shaw. 79

Returning briefly to Washington, D.C., Toomer set out again for New York where he worked as a clerk with the grocery firm Acker, Merrall, and Condit Company. While in New York, his reading expanded to include Ibsen, Santayana, and Goethe; he attended meetings of radicals and the literati at the Rand School, as well as lectures by Alfred Kreymborg, who, a decade later, would describe Toomer as “one of the finest artists among the dark race, if not the finest.” 80In the spring of 1919, he left Manhattan to vacation in the resort town of Ellenville, New York. Indigent though somewhat rested, he then returned to Washington in the fall, where he was confronted by the condemnations of his grandfather who was far from pleased with his grandson’s vagabond existence.

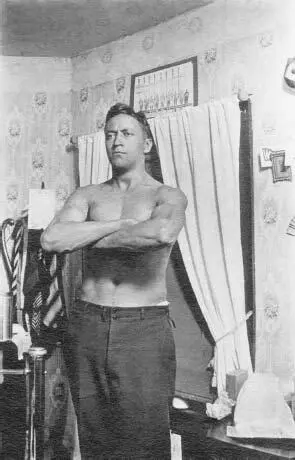

College photograph of Jean Toomer, bare-chested with arms folded, 1916. Jean Toomer Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke and Rare Book Manuscript Library.

Group portrait with Toomer at center (four men in front blindfolded), from the Lunkentus Class of 1917 yearbook (American College of Physical Education). Jean Toomer Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke and Rare Book Manuscript Library.

Unable to endure any longer the aging but vigorous Governor’s harangues on personal responsibility, in December 1919, his twenty-fifth birthday only days away, Toomer was on the road again. With only ten dollars to his name, he walked from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore. Winter had arrived, and as Toomer recalled, it was “cold as the mischief.” 81After an overnight stay in Baltimore, he then walked to Wilmington, Delaware, and from there hitchhiked to Rahway, New Jersey, where he worked for a time as a fitter in the New Jersey shipyards for $22 per week. 82This practical experience with the working class disabused him of his romantic notions about socialism. Toomer’s destination was New York, and when he arrived there he once again took a job at Acker, Merrall and Condit. As he made his way from Washington to New York on Walt Whitman’s open road, as it were, Toomer was alone; his only company was the ambitious, yet unrealized desire to become a writer.

In 1920, Pinchback sold the Washington home that Nathan Toomer had purchased as a wedding present for Nina Pinchback. In spite of his disappointment with his grandson, Pinchback sent Toomer $600, the small profit derived from the sale of the rental property after the payment of the mortgage and taxes. With this windfall, Toomer decided to remain in New York to continue what turned out to be the beginning of his apprenticeship as a writer: “I decided that I was at one of the turning points of my life, and that I needed all my time, and that the money would be well spent. I quit Acker Merrall. I devoted myself to music and literature.” 83And then, through yet another unexpected turn of events, he once again gained entrée into the rather closed world of New York’s literati. In August 1920 he was invited by Helena DeKay, whose lectures on Romain Rolland and Jean-Christophe he had attended at the Rand School, to a party hosted by Lola Ridge, editor of the new literary magazine Broom. “This was my first literary party,” according to Toomer. 84Actually, it would be more accurate for Toomer to claim that Ridge’s soirée was his first “literary party” in New York, for he had attended the literary salons hosted by the black poet Georgia Douglas Johnson in Washington, D.C., as early as 1919. 85Known among the cognoscenti of the nation’s capital as Saturday Nighters, these gatherings attracted such luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance as Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Bruce Nugent, Sterling A. Brown, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, and Alain Locke.

Читать дальше