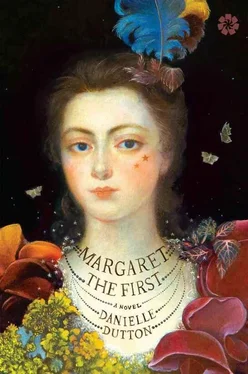

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“These black stars serve,” she says to William, “like well-placed commas, to punctuate my face.”

“They look obscene,” he says.

On May 1 the duchess goes out in her silver carriage.

On May 2 she walks the lawn in a moiré gown.

And Flecknoe tells her — as they walk that lawn — how the previous night he heard someone telling someone else that after visiting at Newcastle House Mary Evelyn told Roger Bohun that women were not meant to be authors or censure the learned — he lifts a low-hanging branch — but to tend the children’s education, observe the husband’s commands, assist the sick, relieve the poor. Everything is white, for the blossoms have come down. The path is white. The grass. Even Margaret’s shawl is white and wrapped around her arms. Eventually, she says: “A woman cannot strive to make known her wit without losing her reputation.” “But you are making yours,” he says. Indeed, people wait to see her pass. They wait at night at the palace, hoping she’ll visit the king. But the papers begin to report on things she never did or said. Is it another Margaret Cavendish parading down London’s streets? On another peculiar outing? In another ridiculous dress? That night she dreams she’s eating little silver fish; each time one fish goes in, ten more come sliding out.

In the morning she tells Lucy she will only sit and read. But she’s promised to visit her sister — so another gown, the carriage, another ride to read about in the papers the following day.

Catherine in middle age looks remarkably like their mother, her hair pulled back as their mother’s always was. Margaret’s own hair is freshly reddened, curled. She might see herself in her sister, yes, but her sister seems so real. How pleasant is the glow of Catherine’s little room. “How nice this is,” Margaret says, and takes a bite of cake. Then all at once her sister’s grandchildren arrive. How simple. How sweet it is. “This is the Duchess of Newcastle,” Catherine says. The children stare with their bright, round eyes. Margaret shifts in the chair. My hat is too tall, she thinks.

Outside, the day is hot.

“It’ll be out of the way,” her driver says.

But Margaret doesn’t care.

So rather than east on Holborn, they sweep down Drury Lane, all the way to Fleet Street, around the remains of what was once St. Paul’s — it’s here she brought her Poems & Fancies in 1652, to Martin & Allestyre at the Sign of the Bell, now burnt to the ground — up Old Change to Cheapside to Threadneedle to Broad. At last she sees the gates. Here is Gresham College. She raps and the driver stops. But as she steps from the carriage, she sees the street is burned. It’s black beneath her boots. At once she remembers William’s words, as if she heard them only now: The Royal Society of London no longer meets at Gresham, damaged in the fire. Then what is she doing here?

As she stands, a crowd begins to form.

On the corner, a sign: a unicorn means an apothecary’s shop. Margaret begins to cross the street. But a hackney coach’s iron wheels come screeching across the stones. She presses herself against a wall. A woman stands beside her, a screaming child slung across her back. When was the last time Margaret walked such streets alone? She opens the door — the shop is dim — but she cannot simply stand there as the apothecary stares. So back into the street, quickly to the carriage. The driver helps her up. The crowd has grown. They point and call, “Mad Madge! Mad Madge!” and mud hits her window as the driver takes a left.

So, it comes. And there’s nothing she can do, even as she feels it come and wishes that it wouldn’t. Mad Madge! Mad Madge! she hears in her head all night.

At dawn, Lucy fetches William and tells him about the crowd. William sends for the doctor. She is only half asleep, half dreaming of that coach, screaming, the screaming baby pressed against the wall. She wakes to the awful shadows of the bed curtains on her arm. “Well,” the doctor says, “no harm was done.” And William — good William — kisses her cheek. Has she been forgiven? He holds her hand as she lies there, bleeding into bowls. When visitors come to the house, the butler tells them the duchess is indisposed. William stays until the doctor’s real cure arrives, a stinking ointment that Lucy has been instructed to spread on her mistress’s legs. “It will open sores,” William explains, “so that the harmful humors might be expelled.” Her hands in waxed gloves, Lucy spreads the salve. Margaret faints from pain. She oozes onto sheets.

Near dawn each day the roosters shout.

At night she hears the bells.

A pattern of days and nights.

Of birds, then bells.

Finally, one afternoon, William leads her to the yard. Her legs are mostly healed. “I think we should have a party,” he says, reaching around to steady his wife. She holds a green umbrella. “To refresh you,” he goes on. The cool air stirs the sores beneath her skirts. “It will be only those friends we’ve known for years,” he says. “Your sister, and Richard Flecknoe, and Sir George Berkeley and his wife.”

The ladies wear satin dresses, the men thick black wigs. Margaret is prepared: she has Latin for one guest, translation for the bishop, sea nymphs for Sir George’s wife. They drink out on the lawn. But the bishop is ill and does not come, and she is seated next to Sir George and not Sir George’s wife. Margaret passes a platter of eels, a calf’s head eaten cold, as Sir George offers a chilled silver bowl with a salad of burdock root. His hands are faintly shaking. “Had you heard,” he loudly says, “I am now an official gentleman member of London’s Royal Society?” “No,” she says, straightening in her chair, “I had not heard.” “Well, well,” he goes on, “you made quite a stir, my dear.” Her Blazing World was passed from man to man. “Quite ruffled,” he laughs, “quite ruffled.” Who was ruffled, she wants to know. But William is asking the old man for news, so Margaret repeats her husband’s question in Sir George’s ruddy ear. And with another laugh, he begins to tell of a recent meeting in which Sir Robert Moray gave an account of an astonishing grove — in Scotland? was it Wales? — its trees encrusted with barnacle shells. “Inside the shells,” he says and chews, “when Moray pried them with his knife, what do you think he found?” He looks the length of the table, for everyone listens now: “Miniature seabirds!” he says. “Curled up and still alive!” The party is delighted. The table shines with light. Margaret watches the salad go, its shining bowl and tongs. But who was ruffled, she wants to know. “Tell us of Robert Boyle,” Catherine’s husband says. “Is it true he walks with a limp?” “You think of his colleague Robert Hooke. A sickly man, though gifted.” “A great man,” someone says. “Then who is Moray?” “Sir Robert Moray,” someone says. “Pardon me,” says Margaret, and everyone turns. “Forgive me,” she says, “but we had been speaking — that is, Sir George had been speaking of my recent book, of comments made at the Royal Society, and not of Sir Robert Moray or Robert Hooke and his limp. You see,” she says, as everyone watches, “I have lately felt a great desire — that is — I would very much like to present my ideas. I would like to speak to the Royal Society. I would like to be invited.”

In Margaret’s Blazing World —with its river of liquid crystal, its caves of moss, and bears — the young lady, inevitably, marries the emperor and, as empress, eventually, begins to feel alone. After the wedding night, she scarcely sees the emperor. Months pass. She has a son. She rarely sees him either. Lonely and bored, she appoints herself the Blazing World’s Patron of Art and Science, names the Bear-men Experimental Philosophers, the Ape-men Chemists, the Lice-men Mathematicians, and calls a convocation of the Bird-men, her Astronomers, instructing them to instruct her in the nature of celestial life.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.