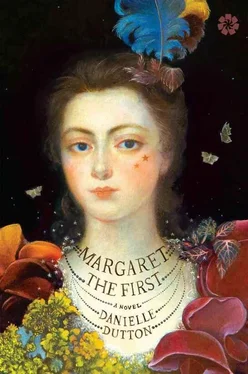

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But I am old, she thinks, turning to the mirror.

She touches her hand to her neck.

Normally, she would begin her writing directly, but her newest book, really two books in one— Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy and The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World, Written by the Thrice Noble, Illustrious, and Excellent Princesse, the Duchess of Newcastle, which she calls one part Fantastical and one part Philosophical, “joined as two Worlds at the end of their Poles,” and in the preface of which she claims to be “as Ambitious as ever any of my Sex was, is, or can be; which makes, that though I cannot be Henry the Fifth, or Charles the Second, yet I endeavour to be Margaret the First” —has just returned from the printer.

She is anxious for its reception, plans to send a copy to the king, copies to Oxford and Cambridge. On her desk this new book sits, leather-bound, a strange and reverent object. It marries, Margaret thinks, all of my life’s work. And she opens it at random to a passage near the start, finding the Emperor of the Blazing World leading the visiting Duchess of Newcastle to see his horse stables of gold, cornelian, amber, and turquoise — they are utterly unique! — whereupon the duchess confesses that “she would not be like others in any thing if it were possible; I endeavor,” she tells him, “to be as singular as I can; for it argues but a mean Nature to imitate others; and though I do not love to be imitated if I can possibly avoid it; yet rather than imitate others, I should chuse to be imitated by others; for my nature is such, that I had rather appear worse in singularity, than better in the Mode.” Surely it shines, she thinks. And she wishes it one thousand or ten thousand million readers. Nay, that their number be infinite! The Blazing World with its blazing sky and river of liquid crystal. Its gowns of alien star-stone! Its talking bears and spiders! William has told her it is her finest work, and even composed a poem to include:

You conquer death, in a perpetual life

And make me famous too in such a wife.

Margaret shuts the book.

Her eyes burn from reading too long by candle last night: one new pamphlet from the Royal Society called “Some Observations of the Effects of Touch and Friction” and another, well-thumbed, from Hooke’s Micrographia; or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon , on the discovery of a new world — not a new world, she thinks, for certainly one’s inability to see something does not mean it is not there until one does — opened for the first time to his sight, with so-called new stars and new motions, and in particular one section regarding the moon, wherein Hooke, observing light near the Hipparchus crater, concludes that the moon “may have Vegetables analogus to our Grass, Shrubs and Trees; and most of these encompassing Hills as may be covered with a thin vegetable Coat, such as the short Sheep pasture which covers the Hills of Salisbury Plains,” as well as the description of an experiment that may, he writes, reveal a hidden world beneath our very feet, beyond the reach of even the most powerful microscope, an alternate universe of harmony and vibration — and hadn’t she thought the very thing herself, and years ago? A world inside a peach pit? Inside a lady’s jewel? Yet he magnifies a flea to fill a folio page, as if to turn nature into a monstrosity is the most profound success. He turns a flea into a thing not wholly flea!

So it’s for the best — it is, and she will not regret it — that in this new book she addresses these men directly. Of Hooke and his Micrographia : “The inspection of a bee through a microscope will bring him no more honey, nor the inspection of a grain more corn.” She calls their microscopy a brittle art. Hooke himself admits it! How the light inside the instrument, coming from different angles, causes a single object to take on many shapes. They distort the very thing they claim to expose! Indeed, she pities the flea. Meanwhile, their so-called observations reveal only the outer shell, and nothing of the inner essence of a thing. The mysteries of nature go utterly unrevealed! She even challenges the Royal Society to debate her ideas in public, for why should it be a disgrace to any man to maintain his opinions against a woman? “After all,” she says to the mirror, “I am a duchess and not unknown,” and she straightens out her heavy skirts, twisted all around.

The light in the room is piercing. Now the clouds have gone, it pours in through tall windows, made harsh by the whiteness outside, echoes sharply off a collection of mirrored boxes and several glass drops — a gift from her old friend Huygens, whose son has just completed his own new book, Systema Saturniam , in which the rings of Saturn are described — so she calls her maid, Lucy, to pull tight the heavy drapes.

“It was a mighty storm, Duchess,” Lucy says as she pulls.

“No letters today?” Margaret asks, still waiting for word from William.

“Not today, Duchess. Though Mr. Tapp says the London road is down with snow. You’ll likelier hear tomorrow.”

Lucy curtsies, closes the door.

Alone again in semidarkness, Margaret stands in the corner and fancies herself a statue, with silken robes and a crown of topaz, erected in a garden, atop a pedestal, at the center of a circle divided into four parts, with lines drawn, and points laid, in the service of some abstruse mathematical thought, and covers her eyes with her palms. She can see her Blazing World before her: the emperor’s bed is made of diamonds. The walls of his room are jet. His penis is made of silver. She opens her eyes. No, it’s just a penis. But there are his horse stables of gold, cornelian, amber, and turquoise. There are his horses. This is his golden city, his flickering canal, his woodsy archipelago stretching all the way to the granite cave where Bear-men sleep on the cool dirt floor. She imagines the salty musk. She imagines the cave steaming, drenched, covered in moss and crystals.

The binding cracks. She sniffs it. Her book smells like a shoe.

Then, as if she’s been struck by alien star-stone, she’s suddenly struck by doubt. Is it ridiculous? Is she a joke? Not that these doubts are new, only here, again, and racing in the dark. And where moments ago she saw a golden city, now there is only this. The fallen snow. This dread. She places the book in a shallow drawer, scans the room to fill her eyes and so to fill her mind: the bed, the mirrors, the tapestries, a portrait of herself. But even with the curtains drawn she finds her eyes are burning, a headache coming fast, and she calls again to Lucy to assist her in retiring to a sofa of pillows embroidered with garden scenes. Off come her skirts and petticoats, her lace cuffs and collar, her shoes and whalebone stay, until she lies on her side in nothing but a cotton shift and endless strands of pearls. Dust hangs in a crack of light between red velvet drapes, like stars.

Her dreams are glimpses, bewildered — celestial charts, oceanic swells, massive, moving bodies of water, the heavens as heavenly liquid, familiar whirlpools, the universe as a ship lost at sea — but the ship she imagines arrived safely, years ago, loaded with their possessions. It’s true her crates took long to find her — something mismarked or misnamed — and she wept for her missing manuscripts as she would have wept for an absent child. Long reconciled to childlessness, she worries instead about barrenness of the brain: “I should have been much Afflicted and accounted the Loss of my Twenty Plays, as the Loss of Twenty Lives,” she’s written, “but howsoever their Paper Bodies are Consumed, like as the Roman Emperours, in Funeral Flames, I cannot say, an Eagle Flies out of them, or that they Turn into a Blazing Star, although they make a great Blazing Light when they Burn”—and as she wakes, her mind alights on something she read last night, Copernicus’s dying words: “It moves!”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.