His investigative reporting is lethally painstaking’ NEAL ACHERSON, Independent ‘Part-memoir, all heart, this 1,328-page behemoth will delight Fisk’s fans, infuriate his foes and fascinate all’ DONALD MORRISON, Financial Times ‘A fierce indictment of Britain and the United States’ Sunday Telegraph ‘A mammoth and magisterial work, the definitive summation of what has gone wrong in the West’s foreign policies towards Arabia. It should be compulsory reading for those who aspire to lead’ Scottish Sunday Herald ‘It is a history book which journalists, politicians and academics will turn to again and again in the years ahead to grasp the details of the Middle East’ WILLIAM GRAHAM, Irish News ‘Fisk is a gifted writer and an accomplished storyteller … [readers] will enjoy the colorful narrative [and] the wealth of hard-won narrative detail accumulated over his decades of intrepid reporting’ Economist ‘Vivid, graphic, intense and very personal … this is a book of unquestionable importance’ Washington Post

DEDICATION DEDICATION For Bill and Peggy, who taught me to love books and history

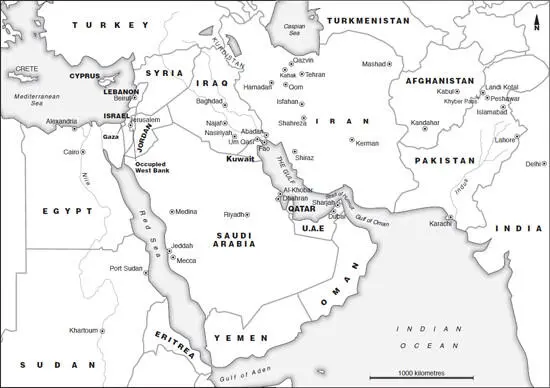

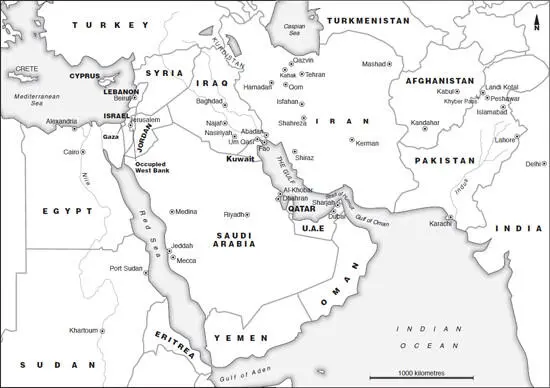

LIST OF MAPS LIST OF MAPS The Middle East Afghanistan Iran Iraq The Sykes-Picot Agreement The Iran—Iraq war The Armenian Genocide Israel/Palestine Algeria Saudi Arabia/Kuwait/Iraq All maps drawn by HLStudios, Long Hanborough, Oxford, except the Armenian Genocide, produced by the Armenian National Institute (ANI) (Washington DC) and the Nubarian Library (Paris). © ANI, English Edition Copyright 1998.

PREFACE

1 ‘One of Our Brothers Had a Dream …’

2 ‘They Shoot Russians’

3 The Choirs of Kandahar

4 The Carpet-Weavers

5 The Path to War

6 ‘The Whirlwind War’

7 ‘War against War’ and the Fast Train to Paradise

8 Drinking the Poisoned Chalice

9 ‘Sentenced to Suffer Death’

10 The First Holocaust

11 Fifty Thousand Miles from Palestine

12 The Last Colonial War

13 The Girl and the Child and Love

14 ‘Anything to Wipe Out a Devil …’

15 Planet Damnation

16 Betrayal

17 The Land of Graves

18 The Plague

19 Now Thrive the Armourers …

20 Even to Kings, He Comes …

21 Why?

22 The Die Is Cast

23 Atomic Dog, Annihilator, Arsonist, Anthrax and Agamemnon

24 Into the Wilderness

KEEP READING

NOTES

FOOTNOTES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHRONOLOGY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

| The Middle East |

|

| Afghanistan |

|

| Iran |

|

| Iraq |

|

| The Sykes-Picot Agreement |

|

| The Iran—Iraq war |

|

| The Armenian Genocide |

|

| Israel/Palestine |

|

| Algeria |

|

| Saudi Arabia/Kuwait/Iraq |

|

All maps drawn by HLStudios, Long Hanborough, Oxford, except the Armenian Genocide, produced by the Armenian National Institute (ANI) (Washington DC) and the Nubarian Library (Paris). © ANI, English Edition Copyright 1998.

When I was a small boy, my father would take me each year around the battlefields of the First World War, the conflict that H. G. Wells called ‘the war to end all wars’. We would set off each summer in our Austin of England and bump along the potholed roads of the Somme, Ypres and Verdun. By the time I was fourteen, I could recite the names of all the offensives: Bapaume, Hill 60, High Wood, Passchendaele … I had seen all the graveyards and I had walked through all the overgrown trenches and touched the rusted helmets of British soldiers and the corroded German mortars in decaying museums. My father was a soldier of the Great War, fighting in the trenches of France because of a shot fired in a city he’d never heard of called Sarajevo. And when he died thirteen years ago at the age of ninety-three, I inherited his campaign medals. One of them depicts a winged victory and on the obverse side are engraved the words: ‘The Great War for Civilisation’.

To my father’s deep concern and my mother’s stoic acceptance, I have spent much of my life in wars. They, too, were fought ‘for civilisation’. In Afghanistan, I watched the Russians fighting for their ‘international duty’ in a conflict against ‘international terror’; their Afghan opponents, of course, were fighting against ‘communist aggression’ and for Allah. I reported from the front lines as the Iranians struggled through what they called the ‘Imposed War’ against Saddam Hussein – who dubbed his 1980 invasion of Iran the ‘Whirlwind War’. I’ve seen the Israelis twice invading Lebanon and then reinvading the Palestinian West Bank in order, so they claimed, to ‘purge the land of terrorism’. I was present as the Algerian military went to war with Islamists for the same ostensible reason, torturing and executing their prisoners with as much abandon as their enemies. Then in 1990 Saddam invaded Kuwait and the Americans sent their armies to the Gulf to liberate the emirate and impose a ‘New World Order’. After the 1991 war, I always wrote down the words ‘new world order’ in my notebook followed by a question mark. In Bosnia, I found Serbs fighting for what they called ‘Serb civilisation’ while their Muslim enemies fought and died for a fading multicultural dream and to save their own lives.

On a mountaintop in Afghanistan, I sat opposite Osama bin Laden in his tent as he uttered his first direct threat against the United States, pausing as I scribbled his words into my notebook by paraffin lamp. ‘God’ and ‘evil’ were what he talked to me about. I was flying over the Atlantic on 11 September 2001 – my plane turned round off Ireland following the attacks on the United States – and so less than three months later I was in Afghanistan, fleeing with the Taliban down a highway west of Kandahar as America bombed the ruins of a country already destroyed by war. I was in the United Nations General Assembly exactly a year after the attacks on America when George Bush talked about Saddam’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction, and prepared to invade Iraq. The first missiles of that invasion swept over my head in Baghdad.

The direct physical results of all these conflicts will remain – and should remain – in my memory until I die. I don’t need to read through my mountain of reporters’ notebooks to remember the Iranian soldiers on the troop train north to Tehran, holding towels and coughing up Saddam’s gas in gobs of blood and mucus as they read the Koran. I need none of my newspaper clippings to recall the father – after an American cluster-bomb attack on Iraq in 2003 – who held out to me what looked like half a crushed loaf of bread but which turned out to be half a crushed baby. Or the mass grave outside Nasiriyah in which I came across the remains of a leg with a steel tube inside and a plastic medical disc still attached to a stump of bone; Saddam’s murderers had taken their victim straight from the hospital where he had his hip replacement to his place of execution in the desert.

I don’t have nightmares about these things. But I remember. The head blasted off the body of a Kosovo Albanian refugee in an American air raid four years earlier, bearded and upright in a bright green field as if a medieval axeman has just cut him down. The corpse of a Kosovo farmer murdered by Serbs, his grave opened by the UN so that he re-emerges from the darkness, bloating in front of us, his belt tightening viciously round his stomach, twice the size of a normal man. The Iraqi soldier at Fao during the Iran – Iraq war who lay curled up like a child in the gun-pit beside me, black with death, a single gold wedding ring glittering on the third finger of his left hand, bright with sunlight and love for a woman who did not know she was a widow. Soldier and civilian, they died in their tens of thousands because death had been concocted for them, morality hitched like a halter round the warhorse so that we could talk about ‘target-rich environments’ and ‘collateral damage’ – that most infantile of attempts to shake off the crime of killing – and report the victory parades, the tearing down of statues and the importance of peace.

Читать дальше