We lay still, our bellies against the ground, and watched him walk towards his death.

He saw the herd, the first sign of life he must have seen in the mountains for days. I thought the sight might make him flee or scour the hillsides for the shepherds who watched over this thieves’ flock. He paused for only a moment, his head cocked to the side, before he went towards the animals in the valley.

We waited until he passed our position, until he was deep within the dale. There was only one way in and out of this place; that is why we had chosen it to keep our herd. If he went deeper into the valley we would have him trapped, for it ended in impassable cliffs. If he tried to go back the way he had come we would have to close the distance quickly, to cut him off before he could escape.

Yet the moment we stood, he seemed to hear us. For he turned to face us and he did not run. He greeted us with a wave, as though he were hailing friends from another valley, and came towards us.

We stood, irresolute. We would have been ready for him to take flight, to draw a weapon. This courtesy was one we did not know how to answer.

‘We should welcome him,’ Thoris said. ‘Let him relax. Then we can take him by surprise.’

‘I will not murder a man like that. If he must die, he will die fighting.’

He cursed me. ‘A fool’s honour,’ he said. ‘You still speak as a free man. But we shall kill him your way.’

I had almost forgotten how free men looked: soft cheeks, clean tunic, silver rings on his arms. We must have seemed a desperate pair to his eyes, I half-handed, Thoris ragged from seven years in the mountains. More akin to wolves than men.

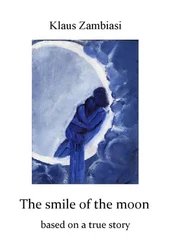

He carried a beautiful weapon, a sword too large to wear slung from his belt, and so he carried its scabbard in his hands like a staff, picking his way through the rocks with the sheathed point. Now he placed that point against the ground and rested his chin on the pommel. He smiled at us and I saw that half his teeth were gone, all on one side. The side of a shield, the flat edge of a sword, a wild horse’s flailing hoof – something had marked him with a monster’s smile.

‘This is your herd?’ he said.

‘It is,’ Thoris replied.

‘I do not think so. They bear the marks of many different men.’

‘They are ours now.’

He covered his mouth with his hand. ‘So I see,’ he said, his shoulders shaking.

‘Who are you?’ I asked.

‘My name is Thorvaldur.’

‘Why have you come here?’

‘I am an outlaw, as you are.’

‘Then go, and find another place.’

He raised an eyebrow. ‘You would let me leave?’ And he covered his mouth again.

I put my hand to the hilt of my sword. ‘We cannot. But we will give you a warrior’s death.’

‘I thank you for speaking the truth.’ He paused, then said: ‘If I cannot leave, perhaps I may join you.’

‘I have no need of another man eating my sheep and grain,’ Thoris said and levelled a finger at me. ‘One parasite is enough.’

‘Oh, I may be of use to you,’ said the stranger.

‘How?’ I said, and I remembered the words that Thoris had spoken to me in the storm. ‘What can you do?’

‘What can I do?’

‘Why should we save you?’

He laughed out loud now, as though at some joke that only he had heard. ‘I can tell you of God,’ he said. ‘Of the true God.’

‘The White Christ?’

‘He is called that by some.’

‘We have gods enough of our own,’ I said. ‘We have no need of yours.’

‘Fool,’ Thoris said. ‘The gods are no friends of ours.’ He looked back on the stranger. ‘But your God will be no different. We have no need of him.’

‘Very well. May I have the names of those who will kill me?’

‘I am Thoris Kin-slayer. And this is Kjaran the Luckless. Tell them to your God, when you see him.’

He cocked his head again. ‘I have heard your story,’ he said. ‘You killed your brother.’

‘Aye. That I did.’

‘My God has a story of such a thing. You shall want to hear it.’ He looked to me next. ‘I do not know your crime. But perhaps I have a story for you as well. I would be happy to share them with you.’ He tightened his grip on the sword. ‘Or we may kill each other. It does not matter to me.’

I have heard many men make such a boast. Our gods honour none but the battle dead, and so we should hold no fear of death at the edge of a blade. Yet for all the boasts I had heard, I believed it from only two men: Gunnar, and the man who stood before us in that valley.

I had heard that Christians were unmanly, that their God was a coward. For that was what the White Christ meant: the Coward Christ. And yet here he was before us, ready to die.

‘Wait,’ Thoris said.

The silence grew. Perhaps he was thinking of the danger of a fight. We were two, but we were weak. He might only have to wound us to kill us: a fever or starvation would finish what he began. Perhaps Thoris merely thought of the odds, and that they were not in our favour.

But I do not think it was that.

‘Your name is Thorvaldur, you say?’

‘Yes.’

‘Thorvaldur,’ Thoris repeated, as though there were some spell in the word. Perhaps there was, for I could not have expected what he next said. ‘You may come with us. I will hear stories of your God.’

At once, the stranger relaxed. He thrust the point of the sword into the snow and came forward to embrace us, as though we were his brothers.

We could have cut him down then; perhaps it would have been better if we had. But he knew that we would not. Already, we were under the strange spell he seemed to cast.

*

And so we were three. A farmer, a poet, a priest.

We took him back to the cave and lit a fire, our first in many days. It amused me to see Thoris light it. Even out here he wanted to impress his guest, as if he were an impoverished chieftain gifting his last silver ring to a visitor rather than confess his poverty. For it is better to starve than to be shamed.

We ate, shared a little of that mead that Thoris kept on the flask around his neck, and sat together in silence. I waited for Thorvaldur to speak, to share the words of his God, but he seemed to feel no haste. He waited for us to ask.

‘How did you come to be outlawed?’ I said.

Thoris’s mouth twisted in scorn. I knew how he hated to speak of a world outside these mountains.

‘I travelled with a bishop,’ the Christian said.

‘What is that?’

‘A great man of God, from across the sea. We travelled together, visiting one chieftain after another. Then we went to the Althing, to speak the word of God.’ He fell silent. It was the first time that I had seen him hesitate, seem doubtful.

‘What happened?’

‘They laughed at us. Called him unmanly.’ He smiled at me. ‘And so I killed two of them. It was a fair fight.’

‘And yet you were outlawed.’

‘They think to cow us Christians. Any other man would have been made to pay the blood-price for answering such an insult. But they thought to get rid of me.’

Thoris spoke at this. ‘They have succeeded, it seems.’

Thorvaldur shrugged. ‘For three years. And then I shall return.’

‘Why not go abroad?’ He pointed to me. ‘This fool had the chance, but gave it up. Were you too proud to leave, too? Or too poor?’

‘Neither. I came here to find men like you.’

‘Why would you do such a thing?’

‘The men out there. They are not ready to hear the word of God. Perhaps you are.’

‘What do we matter to you?’

‘Every soul matters to me. But that is a story for another time.’ He spread his hands wide and said, ‘Now, I will speak to you of my God.’

Читать дальше