Karl tapped his fingers against the table.

“Calm yourself,” I said. “You have no reason to be nervous.”

He placed his cap in his lap. “Why has he invited us? Why tonight?”

I put my hand upon his and he relaxed with my touch. I wondered myself why Hitler had invited us. Did he have information regarding the officers who were plotting against him? Had someone given our secrets away? Did he know I had tried to poison Minna, or that Franz had killed her? Perhaps he wanted to question us about her death. Such useless speculation only fueled my anxiety.

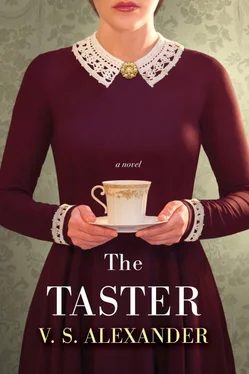

The door opened after a quick knock and the valet appeared, followed closely by another. The valet I recognized from the Berghof held a bouquet of red long-stem roses, which he presented to me. “These are from the Führer,” he said. “He will be here soon.” He then ordered the other man to wheel in a cart loaded with coffee, tea, plates of cookies and slices of apple cake. I laughed to myself because I had tasted all this food earlier. The valets left us and a short time later the door swung open again.

Hitler appeared with Blondi by his side. Karl clutched his cap. We both rose and gave the Nazi salute. Hitler motioned for us to sit down. We, like Blondi, obeyed. Hitler looked more relaxed than I had ever seen him. A slight flush of color infused his cheeks, which were generally pasty because of his aversion to sunlight. His valet pulled out the chair next to me and the Führer sat. For a time, he said nothing, only looked at us with his riveting blue eyes. One could sense the fire burning underneath them. Rasputin’s eyes must have had the same effect upon his followers.

Once again, I felt overwhelmed by Hitler’s presence as if some powerful force emanated from him. What was it—the sheer force of his will? I could see how easy it would be, like the rest of the nation, to be swept up in the endless flow of his propaganda on radio and in films. What power he held over the German people!

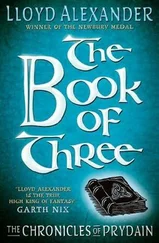

A circular medallion was pinned on his black jacket. It consisted of a gold wreath on the outer layer bordered by a white band, and an inner red band with NSDAP written upon it, all of this encircling a black swastika on a white background.

Karl and I dared not speak until he had spoken to us.

“I am happy to see you,” he said, breaking open the conversation. He spoke in that deep baritone voice I had heard so often when he addressed the Reich. His speech pattern carried its own cadence, a rhythm that was in itself hypnotic. “I hope we can enjoy the evening—I treasure what free time I have, for I am always called away from moments like these for some nasty business, unless I tell my adjutant not to disturb me.” He motioned for his valet to serve tea.

Blondi curled up near Hitler’s feet and looked at me with her soft brown eyes.

“My Führer,” Karl said. “We are delighted you have invited us to tea, but Fräulein Ritter and I are somewhat perplexed by your invitation. How can we be of service?”

Hitler held up his hand. “That’s noble of you, Weber, but you must leave your concerns outside the room.” He put both hands on the table, leaned forward and studied us. “I want no talk of war, or battles, or strategy tonight. In the tearoom we talk of art, architecture and music. We celebrate German culture and history, and tonight we are here to celebrate love.”

“My Führer?” Karl asked, caught as much off guard as I.

The valet served me tea, then took my beautiful red roses and placed them in a crystal vase in the center of the table, so all of us could enjoy them. Their sweet fragrance soon filled the room, a welcome change from the musty, damp odor that permeated most of the bunkers.

Hitler smiled and held up his cup. “I must thank the taster who suffered under Otto’s hands.” He paused and my nerves tightened. “But there is more to discuss.” Karl’s leg brushed against mine and I sensed the tension in his body.

Hitler took a sip of tea and patted my hand. “I try to greet everyone, to say hello, to have a kind word for all who serve the Reich, but I am a busy man. I don’t have much time. You should convey my thanks to all in the kitchen. Several new young women have started recently. I promised Dora I would meet them.”

His eyes flashed with a spark of what I would call “good will.” I had no doubt he would come to the mess hall and greet the new staff. At the moment, he seemed the picture of the kindly father who wanted his “children” to be happy, to do well in a world under his guidance. From his mood, it appeared he believed no one on his staff would ever think of harming him. This attitude of benevolence was more than posturing. Hitler was sincere, but I also knew that any crime against the Reich would be punished in the most severe manner possible.

“Cook has told me,” he continued, “that you two spend a great deal of time together.”

The blood rushed to my head and I blushed, more out of anxiety than embarrassment. So, it was Cook who had revealed our relationship.

“Magda and I have struck up a friendship,” Karl said.

I was dumbfounded by how easily he admitted it.

“We have our jobs to do,” I said, trying to earn some distance between Karl and me. “Fate has thrown us together because we both happen to work in the same area.”

“Yes, but it has been noted,” Hitler said. “Therefore, I wish to give you my blessing.”

Karl went white and I gasped. “My Führer, that is not necessary,” I said.

He waved his hands in protest. “Of course it’s necessary. I have given so many blessings, it’s like a second job; my secretaries, my staff, have all benefited. I encourage my officers to find young women of quality.” He took another sip of tea and nibbled on a slice of apple cake. “Eat up; you haven’t touched the delicious desserts made especially for you.”

“My Führer,” I said. “I tasted them this evening.”

He smiled in mock surprise and laughed. “In that case you can enjoy them knowing they are not poisoned.” He paused and then said, “One issue remained, but I solved it.”

Karl and I looked at each other.

“You are not a Party member, Fräulein Ritter,” Hitler said, “so I have made you one.” He withdrew a box from his jacket and handed it to me.

I took off the lid, unwrapped the paper inside and uncovered a medallion like the one he wore.

“The number on it signifies your place in the Party membership. Mine is ‘one.’” He pointed to the medal on his jacket.

“Thank you.” Uncertain whether to put the medallion on, I closed the box and placed it on the table.

Hitler then turned the conversation to Bavaria and the Alps, rhapsodizing upon the mythology surrounding the Obersalzberg. Karl and I sat, unsettled, for the rest of the evening while Hitler talked about Speer and his plans for the capital and the state of German art and film. Hitler even invited us to his study to listen to a recording of Wagner. It was after midnight when we were dismissed.

We stood for a time outside the bunker door not knowing what to say. An early fall chill had crept into the air and the cooler temperature felt good against my skin. Now that we were “blessed” there seemed little need for pretense. I held Karl’s hand tightly as we walked down the path. I silently marveled that I’d had tea with the leader of the Third Reich. I understood now, in Hitler’s presence, how persuasive, how forceful, he could be. No wonder the German people followed him like sheep. My father had told me of a film called Triumph of the Will . He said its only point was to glorify the Party. I’d never seen it, but I could understand how such a powerful presence could be transferred to the screen and what a great impact it might have.

Читать дальше