She lowered her voice. “May I see?”

“ Now, Madame Professor?” asked Lucius.

“After,” she said.

When the meal ended, she said, “Can the student walk me home?”

The rector, who seemed to want this honor for himself, reluctantly agreed. Zimmer, by then completely drunk, waved Lucius off.

She was staying at the Metropole. Inside the lobby, as they waited for the lift, Lucius could sense the eyes of the bellhop appraise the rendezvous. Oh, but it is not what you are thinking, thought Lucius, though a little flattered by the suggestion. Just looking at a mermaid, that is all…

Upstairs, she led him into the bathroom, with a tall four-legged tub. Lucius opened the rucksack, and she lifted the creature out.

“Oh, dear,” she said. She held it close to the light. In the mirror, Lucius could see all three of them. “How very ugly!” she said. She turned it. “The face looks very much like the old American president Theodore Roosevelt, don’t you think? If she had a little moustache and glasses…”

“Yes, Madame Professor. If the American president were desiccated and had a tail, I think they would look very much the same.”

Lucius, who had the student’s habit of answering in complete sentences that recapitulated the question and expanded it slightly, had actually not meant this to be a joke, but Madame Curie began to laugh. Then she shook her head. “Why in the world are you carrying this?”

“Professor Zimmer… wanted to radiograph it… It is from the collection of Rudolf II. A gift from the Sultan. He thought he might see if the vertebrae of the tail and thorax articulated…”

“Articulated? He actually believes it’s real?”

“It is a possibility he—we—have considered.” In the mirror, Lucius could see his face turning bright red. “The radiograph has allowed the investigation of phenomena…”

She interrupted sharply, “And what does the student think?”

“I think it is a hoax, Madame Professor. I believe it is a monkey and a sarcopterygian fish.”

“Why is that?”

“Because I can see the thread, Madame Professor. See, if you look closely, under this scale.”

He showed her.

“Oh, dear,” she said. “You’re trapped, aren’t you?” She handed the mermaid back. Then, “The rector speaks of you with admiration. If you don’t mind some personal advice, between countrymen. Save yourself. Genius favors the young. You are running out of time.”

But leaving his professor was not that easy.

Against his better judgment, he could not help but feel a filial affection. By then, he had begun to dream the two of them addressed each other with the informal du. So when Zimmer declared the radiographs “inconclusive,” Lucius told the old man that he needed to spend more time back in the library, in order to find a compound that could better serve their needs.

He began to attend class again.

Pathological Anatomy, with lab and lectures.

Pathological Histology, with lab and lectures.

Pathological Anatomy, with autopsy work (Feuermann: “At last, a patient!”).

General Pharmacology, with its long lists of drugs to memorize, but no one to prescribe them to.

Back in the amphitheaters, peering down onto the stage.

And on. Until the summer of his third year, when, with two years of studies remaining and his impatience again almost unbearable, fortune intervened, this time bursting from the pistol of Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo and into the bodies of the archduke and his wife.

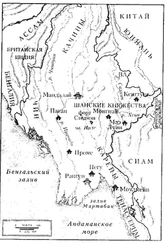

At first Lucius did not appreciate the opportunity of war, declared that July. He saw the efforts of mobilization as disruptive to his studies and feared the rumors that classes would be suspended. He did not understand the patriotism of his classmates, so drunk with a sense of destiny, vacating the libraries so that they might attend the marches, lining up together to enlist. He did not join them when they gathered around maps showing the advance of the Austro-Hungarian Imperial and Royal Army into Serbia, or the German march through Belgium, or the engagement with Russian forces at the Masurian Lakes. He had no interest in the editorials exalting “the escape from world stagnation” and “the rejuvenation of the German soul.” When his cousin Witold, two years his junior and recently arrived from Kraków, told him with tearful eyes that he had enlisted as a foot soldier because, for the first time in his life, the war had made him feel like he was Austrian, Lucius answered in Polish that the war had also apparently made him an idiot, and he would do nothing but get himself killed.

But the celebrations were hard to ignore. It seemed as if the entire city reeked of rotting flowers. In the city parks, errant streamers tangled themselves in the rosebushes, and everywhere, Lucius saw garlanded soldiers walking with beaming girlfriends on their arms. Cinemas offered wartime specials with short clips like “Our Factories at Work” and “He Stops to Bandage a Friend.” In the hospital, the nurses debated the problems of gauge coordination for Austrian trains advancing over Russian rails. Portraits of the enemy appeared in the papers to illustrate their brutelike physiognomies. At home his nephews sang,

Pretty Crista,

At the Dniester.

How she cried!

Cossack bride.

He ignored them.

Zeppelins flew past, dipping their noses above the Hofburg palace in deference to the Emperor.

Then, a few weeks in, rumors of physician shortages began to come.

They were only rumors at first—the army would not publicly admit to such poor planning. But quietly changes were announced at the medical school. Early graduation was offered to those who would enlist. Students with but four semesters of medical studies were made medical lieutenants, and those with six, like Lucius, offered positions on staffs of four or five doctors, in garrison hospitals serving entire regiments of three thousand men. By late August, Kaminski was at a regimental hospital in southern Hungary, and Feuermann assigned to the Serbian front.

Two days before his friend’s departure, Lucius met Feuermann at Café Landtmann. It was covered with bunting and overflowed with families on one last outing with their sons. Since his enlistment, Feuermann seemed to be whistling constantly. His hair was trimmed; he wore a little moustache of which he seemed unduly proud. On his uniform he had pinned an Austrian flag next to his Star of David badge from the Hakoah sports club where he swam. Lucius should reconsider, he said, sipping from a beer decorated with a black and yellow ribbon. If not out of loyalty to the Emperor, then loyalty to Medicine. Didn’t he understand how many years he would have to wait before he saw such cases? Galen learned on gladiators! Within days Feuermann would be operating, while Lucius, if he stayed in Vienna, would be lucky to be the twentieth to listen to a patient’s heart.

In the street, a band led a festooned ambulance from a Rescue Society, followed by a rank of wasp-waisted women in white summer dresses and fluttering hats. Little boys weaved through them, waving streamers of colored crepe.

Lucius shook his head. More than any of his classmates, he deserved such a posting. But in two years they would graduate. And then on to academic posts, real medicine, to something worthy of their capabilities. Anyone could learn first aid…

Feuermann removed his glasses and held them to the light. “A girl kissed me, Krzelewski. Such a pretty girl, and on the lips. Just last night, in the Hofgarten, during the celebration after the parade.” He put his glasses back on. “Kaminski said one actually threw him her knickers at the train station. Frilled and all. A girl he’d never even met.”

Читать дальше