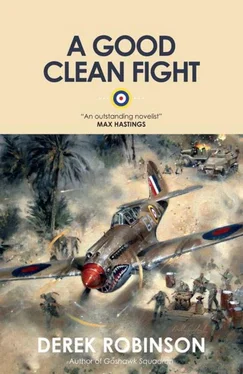

The Desert Air Force never stopped fighting. It had a lot of Curtiss Tomahawks and Kittyhawks. Many Allied pilots liked these aircraft, but without doubt the higher they flew, the less well they performed. (A New Zealand pilot told me that his Kittyhawk had once been outclimbed by a Liberator—a four-engined bomber. Admittedly, the bomber had dropped its load.) However, as a groundstrafer the Tomahawk or Kittyhawk was a great success.

My description of the work of the SAS—the fact that they drove vast distances in order to outflank the enemy; that they hid up in the Jebel; raided airfields by night either silently, with bombs, or loudly, with armed jeeps; and then made the long return journey through the desert—is broadly accurate. So is the scale of the damage they inflicted. For instance, one patrol bombed thirty-seven aircraft at Agedabia airfield; another blew up twenty-seven at Tamit; a third destroyed thirty at Barce. David Stirling led no fewer than eighteen armed jeeps onto a German aerodrome known as LG 12 and in the space of a few minutes machine-gunned rows of Me 109s, Stukas, Heinkel Ills and Junkers 52s. In all, the SAS destroyed more than two hundred and fifty enemy aircraft between December 1941 and August 1942.

It was daring work, and the motto of the SAS is, of course, Who Dares Wins. They did not always win without loss. Usually they struck hard and escaped fast—the German army was curiously reluctant to retaliate and, as far as I know, Major Jakowski’s force had no counterpart in reality. But any SAS patrol that got caught in the open by Stukas or Me 109s was likely to suffer badly.

Special operations called for special qualities. Those who served in the SAS were not wild men, but there can be no doubt that some had more than a touch of recklessness. One of the most remarkable was Captain Paddy Mayne, a big, quick-thinking Ulsterman who had been an Irish rugby international before the war. Mayne was apparently quiet, even reserved, but he had an explosive temper. On rugby tours he had been known to throw fellow players out of hotel windows for no particular reason. When Stirling began to recruit officers, he had to get Mayne out of close detention (he had knocked out a superior officer as a means of settling an argument) and the Irishman made it clear that he was interested in only one thing: fighting.

Mayne inspired huge faith in the men he led. One famous story describes how he ran out of bombs and so he ripped the instrument panel from a Messerschmitt in order to disable it. When not on operations he could be moody and bloody-minded to the point of irresponsibility. (Those who drank with him learned to be very wary.) When Stirling left him at base with orders to train some new recruits while Stirling went raiding, Mayne felt snubbed. He built himself a large bed and lay on it, reading, for days on end. Stirling came back and was furious at Mayne’s negligence. Mayne was only good for combat. At that he was superb: before the war was over he had been awarded four Distinguished Service Orders. To win one DSO is a great achievement; to win four is phenomenal.

All the characters in A Good Clean Fight are invented, and certainly Jack Lampard is not based on Paddy Mayne. However, when I was writing the story I was aware that there was room for powerful individuals inside the SAS, and that quirks of behavior were acceptable so long as the individual got results. (Mayne survived the war, but never settled in civilian life; he died in December 1955 when he drove his car into the back of a parked lorry.) Incidentally, as far as I know, Department SU in Cairo did not exist.

As for the unpleasantness at the Black Cat Club: I made it up. This is not to say that troops on leave in Cairo never misbehaved. Men of the Special Forces certainly relaxed in their own way. In Long Range Desert Group (Collins, 1945), Captain W. B. Kennedy Shaw recalled certain incidents involving that unit “which ended in the Military Police barracks at Bab el Hadid.” For instance, the LRDG was proud of its skill at sand-channeling, the technique of placing steel channels under wheels to extricate a vehicle stuck in soft sand, and one patrol “insisted on sand-channeling their way down the length of Sharia Suleiman Pasha”—a main street in Cairo—“to the fury of the police and the dislocation of the traffic.” There were other incidents (one involved a bath and a lift-shaft) and friction developed when men not in the LRDG were found wearing its shoulder patches because these “were always good for a few free drinks.” I borrowed this act of dangerous larceny and applied it to the white berets of the SAS instead—an item of clothing which did in fact provoke confrontations in Cairo, until Stirling changed its color.

There was no Hornet Squadron in North Africa, but anonymous airstrips such as LG 181 were in fact dotted all across the Western Desert. At one time the Desert Air Force used LG 125, which was well behind enemy lines; I doubled it for luck and called it LG 250. Air Commodore Collishaw’s policy of foxing the Italian air force was a reality, but it was not such a total success as some historians have suggested. Like Barton, Collishaw sometimes pushed his luck too far and his squadrons took heavy punishment. Like Barton, Collishaw tolerated no questioning of his orders. On one occasion he sent a squadron of Blenheims to attack the same target for the fourth day running. The squadron commander pointed out that this really was asking for trouble. Collishaw insisted the raid was the last thing the enemy would expect. “We’re going to fox ’em,” he said. The squadron commander still protested. Collishaw asked: “Are you trying to tell me that you haven’t the guts to do your job?” The squadron took off and was swamped by enemy fighters over the target. Only two of its nine Blenheims survived. For once, the enemy had not been foxed.

The manner of Kit Carson’s dying is based on the experience of a fighter pilot in North Africa, who told me how easy it was, in the haste of baling-out, to release the parachute harness—simply from force of habit. He himself very nearly did it; and he is convinced that a member of his squadron really did do it.

The episode involving Butcher Bailey’s return to LG 181 on the back of a German motorcycle combination is based on an actual incident in the desert. Similarly, Hick Hooper’s encounter with exploding ambulances was suggested to me by the experience of a friend who was ground-strafing over northern France in 1944 when he saw a German ambulance blow up spectacularly. Thereafter, he said, he strafed every German ambulance he saw; most of them exploded. He believed they were carrying ammunition. The presence of an American pilot in the desert was not unusual. Many squadrons were made up of pilots from several countries, and by 1942 there were two American fighter squadrons in the Middle East.

The Takoradi Trail is fact. So is the Luftwaffe’s raid on Fort Lamy. The Trail covered 3,697 miles and the journey took six days. The first two thousand miles were the worst: “where the weather was uniformly unaccountable and forced landings offered an agreeable choice between impenetrable forest and empty wilderness,” as the historian Philip Guedalla observed. One machine in ten failed to complete the journey. Nevertheless, over five thousand aircraft took the Takoradi route to Egypt, and Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder said of the men who made possible this steady transfusion, “without their loyal, ever-willing, and tireless assistance our recent successes would have been impossible.” Air superiority preceded ground victory.

The Luftwaffe knew this. As Francis K. Mason has described in The Hawker Hurricane , a Heinkel 111H took off from a remote airstrip called Campo Uno , deep in the south of the Libyan desert, at eight a.m. on January 21, 1942. Its crew included a German explorer, Hauptmann Blaich, and an Italian desert expert, Major Count Vimercati. The Heinkel reached Fort Lamy at two-thirty p.m., bombed the airfield, destroying eight Hurricanes and eighty thousand gallons of fuel, and headed back the way it had come. At six-thirty p.m., after ten and a half hours in the air, it ran out of fuel and made a forced landing in the desert.

Читать дальше